US Banks On Hook For $150 Billion In “Frozen Loans” As Millions Of Americans Skip Credit Card And Car Payments

Tyler Durden

Wed, 05/20/2020 – 18:45

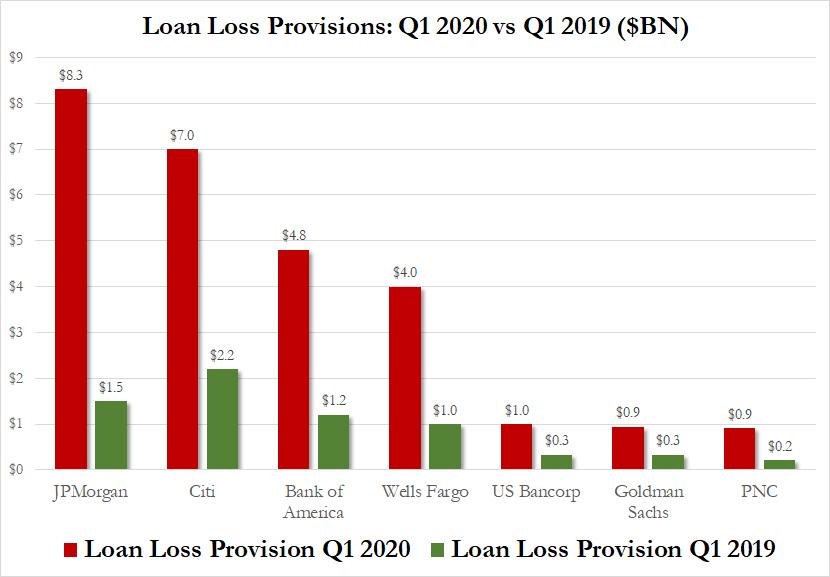

One month ago, after the banks reported Q1 earnings, we showed that the major US money center banks saw their loan loss provisions surge by roughly 4x from year ago levels in response to expected deterioration in their loan books, with JPMorgan jumping the most, or just over 5x, hinting the other banks are likely underprovisioned for the storm that is coming.

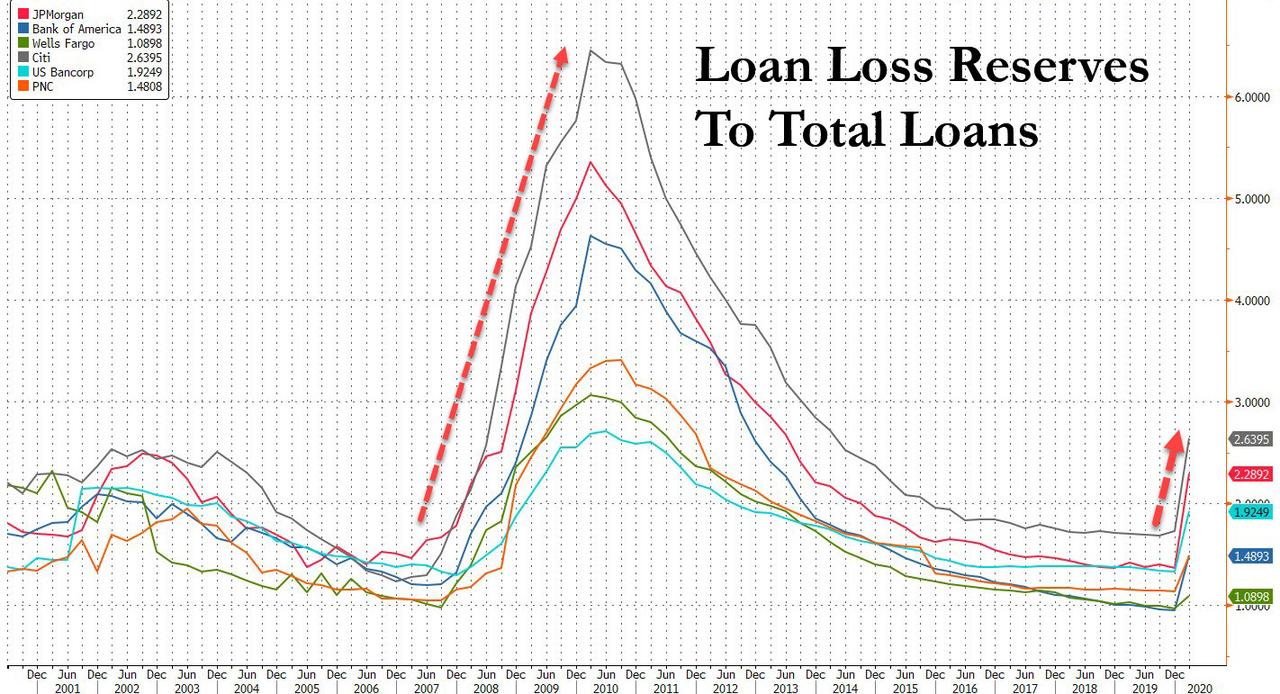

With banks set to be hit with tens of billions in charge offs – for which they are trying their best to reserve even if they have no idea just how bad the hit will be – we next looked at what the banks did in the aftermath of the financial crisis. What we found is that most banks reserved total losses anywhere between 4 and 6% of total loans. This time around? So far it is less than 2%, as shown in the chart below.

Putting it in context, so far the Big 4 banks have reserved an additional $24BN in Q1 for future loses. But if the GFC is any indication of the defaults that are about to be unleashed, the real amount of losses, discharges and delinquencies will increase 3x-4x compared to the current baseline, meaning that over the next several quarters, banks will have to take another $75-$100BN in reserves on loans that go bad, wiping out years of profits, which were used not for a rainy day fund but to pay for – drumroll – buybacks.

As we concluded, “this to put it mildly, is a major problem for banks which until now were seen as generously overcapitalized, because if the US banking sector is facing $100BN (or more) in loan losses, then the Fed will have no choice but to once again step in and bail out the US financial sector.”

Of course, merely delinquent debt does not mean it is automatically in default, a state that usually follows several months of non-payment. However, the longer consumers ignore, or are simply unable to make a scheduled payment, the higher the odds that a delinquent loan will eventually end up in default, resulting in a loan loss for the issuer bank. Ultimately, the total amount of loan losses will dictate if banks are over or under-reserved.

The question, then, is whether our worst-case $100 billion estimate was in the ballpark?

Well, it now appears that this estimate may be optimistic, because as Bloomberg writes today, millions of Americans who have so far been getting breaks on roughly $150 billion loans in are about to hear from their banks. The reason: banks are starting to take a closer look at consumers who have arranged to delay payments, “potentially pushing some out of the programs, as the industry tries to get a clearer picture of how many customers are truly unable to keep up during the coronavirus pandemic.”

It all started with the shock from the enforced shutdowns in March, when as coronavirus cases surged in the U.S. and businesses shut down, millions of people told their lenders they wouldn’t be able to pay their bills. In response lenders allowed borrowers to miss payments for as long as several months on credit cards, auto loans and personal loans.

And while millions of Americans have been ignoring their monthly credit card and auto loan statements, perhaps hoping that banks will simply forget about their obligations, the forbearance programs from March are nearing expiration dates, when many banks are set to decide whether to continue letting people put off roughly $150 billion of debt including credit cards balances, personal loans and car payments. And in interviews with Bloomberg, executives said they’re concerned that at least some borrowers sought relief unnecessarily and that they should be coaxed into paying. And in what is set to be the next major firestorm, a number of firms aim to whittle out such participants, or charge interest to continue.

“I would imagine we may have to go beyond 90 days” of forbearance, Southern Bancorp Inc. Chief Executive Officer Darrin Williams said in an interview, referring to the expiration date for many programs. “I feel pretty strongly that many of the folks who took advantage of the consumer payment holiday we provided probably didn’t have to. But if it’s offered, why not, right?”

To be sure, the rapid rollout of forbearance programs in March averted financial ruin for millions of households, giving Congress time to unleash trillions in fiscal stimulus including unemployment benefits and offer emergency aid to businesses, not to mention give the Fed time to prop up the market, to which roughly 70% of total US household assets are linked. The goal was to avoid a tidal wave of defaults by borrowers who began losing income when states locked down commerce to slow infections. More than 30 million people have since filed jobless claims.

In an attempt to avoid shocking the US economy into a depression, many banks offered to postpone bills with no proof of hardship, and many borrowers kept working. Some signed up for the programs as a precaution, taking a break from payments to shore up their savings. That, according to Bloomberg, made it impossible for banks to gauge the degree to which their loan portfolios are at risk of going bad.

Now, two months later, the dust from the initial shock has settled and banks are starting to assess just how much exposure they have to tens of millions of unemployed Americans who collectively owe over $100 billion in debt.

The numbers are staggering: according to a report from Janney Montgomery Scott analysts last week, some mid-sized banks placed more than 15% of their loan books into forbearance by the end of March.

Needless to say, that number of orders of magnitude greater than what most banks have reserved for total loan losses. In regions like the U.S. Southeast, relatively high rates of borrower relief contrasted with low infection rates at the time. Since then, many programs have remained open, continuing to take on borrowers who have fallen on hard times. As a result, the erosion in bank loan books has only accelerated in the past month; meanwhile of those who voluntarily accepted the forbearance option, there has been virtually no “return to normal”, as most are unable to, or simply resume to restart their debt payments.

Quantifying the forbearance shortfall, credit-reporting firm Transunion reported that lenders in April had nearly 15 million credit cards in “financial hardship” programs, such as the abovementioned deferral programs that let borrowers temporarily stop making payments. That accounts for about 3% of the credit-card accounts the company tracks, Transunion said Wednesday. Separately, nearly three million auto loans were in these hardship programs, accounting for about 3.5% of those tracked. The numbers have surged from a year ago, when 0.03% of credit cards and about 0.5% of auto loans were in financial-hardship programs.

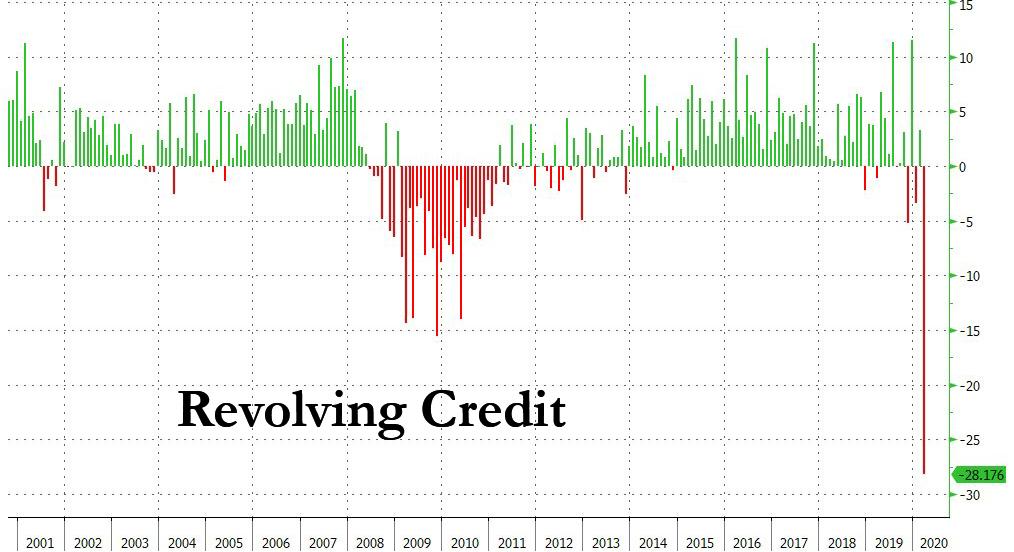

Keep in mind, these numbers only represent accounts in forbearance, they do not reflect those loans which are still current yet which may soon be impaired after the debtor stops making a payment in the coming months. To make matters worse, Americans were tapping credit cards and auto loans at record levels even before the pandemic to deal with rising costs and stagnant incomes, although in a sharp reverse from this trend, March saw a record repayment on credit card debt as those who could, paid down as much of their statement as possible, to clean up their balance sheet.

It is all those who were unable to do so, or were forced to take on even more debt, that are a challenge to the banks.

In addition, about 840,000 personal loans were in deferment or another type of financial hardship in April, accounting for 3.6% of those tracked. TransUnion’s estimates include accounts where the borrowers are pausing their payments with permission, as well as accounts that have been frozen.

* * *

What happens next? Well, as the WSJ notes, the stakes are high for borrowers and lenders alike. Consumers who can’t pay could be sent to collections. Their credit scores could also drop significantly, making it harder for them to access affordable credit in the future.

Lenders could face a reckoning, too. Allowing borrowers to pause their payments lets lenders avoid a big spike in delinquencies and charge-offs, at least for the short term. Credit cards in deferment, for example, aren’t factored into the delinquency rates that many lenders report. And yet, while in this carefully choreographed dance of mutual assured destruction lenders hope that being flexible with borrowers will buy time for the economy to recover and for consumers to get back on track with payments, borrowers may simply have no choice but to default. Furthermore, lenders can only shoulder the unpaid loans for so long, and many are bracing for a mountain of defaults that they’ll eventually write off as a loss.

The question is how much?

Going back to the report from Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, on average, banks had about 5% of their consumer loan portfolios on ice as of mid- to late-April. Based on Federal Reserve data, that would equate to roughly $150 billion in loans, although that amount is surely far greater now as millions more have lost their jobs in recent weeks.

Also keep in mind that those figures don’t include U.S. mortgage forbearance programs that let borrowers with government-backed loans postpone payments for as long as 12 months while dealing with the pandemic; that’s hundreds of billions more than are currently in forebearance and may go straight to default once the extension period ends.

* * *

These millions of consumer-loan deferrals have left banks, shareholders and even regulators in the dark on how many people are truly in distress and what the ultimate cost to lenders may be. While executives expect to get a clearer view of the situation in the second half of the year, for now regulators are letting banks put off that reckoning. In March, a bevy of watchdogs made it easier for lenders to modify terms, such as by lowering interest rates or letting borrowers skip payments. The moves wouldn’t necessarily require banks to label those situations as “troubled debt restructurings,” which require more capital.

The bottom line is that the confusion will likely persist for another quarter, at which point shareholders and regulators will start demanding answers.

“My belief is losses aren’t coming until third quarter for banks,” Ira Robbins, CEO of Valley National Bancorp, said in an interview. Because banks granted deferrals to pretty much everyone who asked for it, “we have no idea, outside of hypothesis, as to what’s going to happen from a credit perspective.”

In advance of what is shaping up as a D-day for the bank, they are now starting to examine millions of account holders to determine who is taking advantage of the programs and who genuinely needs forbearance. The efforts include trying to figure out which customers still have jobs by checking databases operated by major credit reporting firms, according to Bloomberg.

Moving ahead, some banks are considering letting customers continue skipping payments but reinstating interest on loans, a move that could make forbearance less enticing for those who don’t absolutely need it. Others might require customers to show additional proof they’ve been impacted by the virus.

“The banks want to genuinely help,” said Scott Barton, managing partner at 2nd Order Solutions, which advises lenders on collections and forbearance processes. But they “would like to start to differentiate and not give away money to people that don’t really need it right now.”

It’s not that they “want to genuinely help” – it’s that they know that once they accelerate a default, they will have to show it on their books as deferred payments don’t impact delinquent amounts. Meanwhile, the banks also know that in all the chaos, millions of Americans are taking advantage of the forbearance program, but if they did too hard, they will have to disclose the full severity of just how big the hit to their balance sheet will be.

Which, for once, gives US consumers all the leverage in the neverending battle between man and bank.

Forbearance deadlines vary by bank and customer. Citigroup Inc. was one of the first banks to offer forbearance, initially granting a 30-day reprieve that it since extended twice until May 31. Which means that in less than two weeks, millions of Americans will have to start paying down their debt.

Will they?

That’s the $64 trillion question, one which nobody really wants answered. According to Bloomberg, the nation’s largest banks JPMorgan, Bank of America and Wells Fargo – have generally said they will at least check in with borrowers in coming weeks as they assess how to continue programs and whether to encourage people to use other options. Those can include modifying loans or restarting some payments for credit cards or car loans.

The good news is that so far, the programs seem to be easing financial strains during the pandemic. Fewer households were late on their cards, car loans, personal loans and mortgages in April than in March, according to TransUnion data released Wednesday, but here too it’s not clear if the banks are in fact motivated to disclose the full severity of the delinquency rate to data collectors. That upended expectations that consumers would fall behind on their debts as a result of widespread joblessness and the forced shutdown of the U.S. economy. Of course, a big reason for why the default surge has not hit yet is that government stimulus checks continue to plug the income gap for millions of households. But those, too, will soon run out.

Matt Komos, TransUnion’s vice president of research and consulting, said households may be postponing payments to keep an extra cash cushion just in case the economy worsens. Indeed, many consumers who deferred loans sent payments anyway, sometimes far more than the monthly minimums to reduce their overall debt loads, TransUnion data show.

“A lot of the banks are in the dark a little bit in terms of how to treat customers,” said Alan McIntyre, senior managing director for Accenture Plc’s banking practice. “The measures they focus on to manage credit quality, and those dials aren’t moving. And those dials aren’t going to move until the fall.”

That’s when the real shock from the second great depression will finally be revealed.

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com