Europe Has Been Preparing A Global Gold Standard Since The 1970s

Tyler Durden

Mon, 07/20/2020 – 03:30

Submitted by Jan Nieuwenhuijs from Voima Gold,

The current fiat international monetary system is ending—unconventional monetary policy has entered a dead end street and can’t reverse. I have written about this before, and will not repeat this message in today’s article. Instead, we will discuss a topic that deserves more attention, namely that European central banks saw this coming decades ago when the world shifted to a pure paper money standard. Accordingly, European central banks have carefully prepared a new monetary system based on gold.

When the last vestige of the gold standard was terminated by the U.S. in 1971, circumstances forced European central banks go along with the dollar hegemony, for the time being. Sentiment in Europe, however, was to counter dollar dominance and slowly prepare a new arrangement. Currently, central banks in Europe are signaling that a new system that incorporates gold is approaching.

If you want to read a summary of this article you can skip to the conclusion.

Contents:

- The Rise and Fall of Bretton Woods

- Europe Equalizes Gold Reserves Internationally

- Private Gold Ownership Distribution

- Setting the Stage for a Gold Standard

- Conclusion

- Sources

The Rise and Fall of Bretton Woods

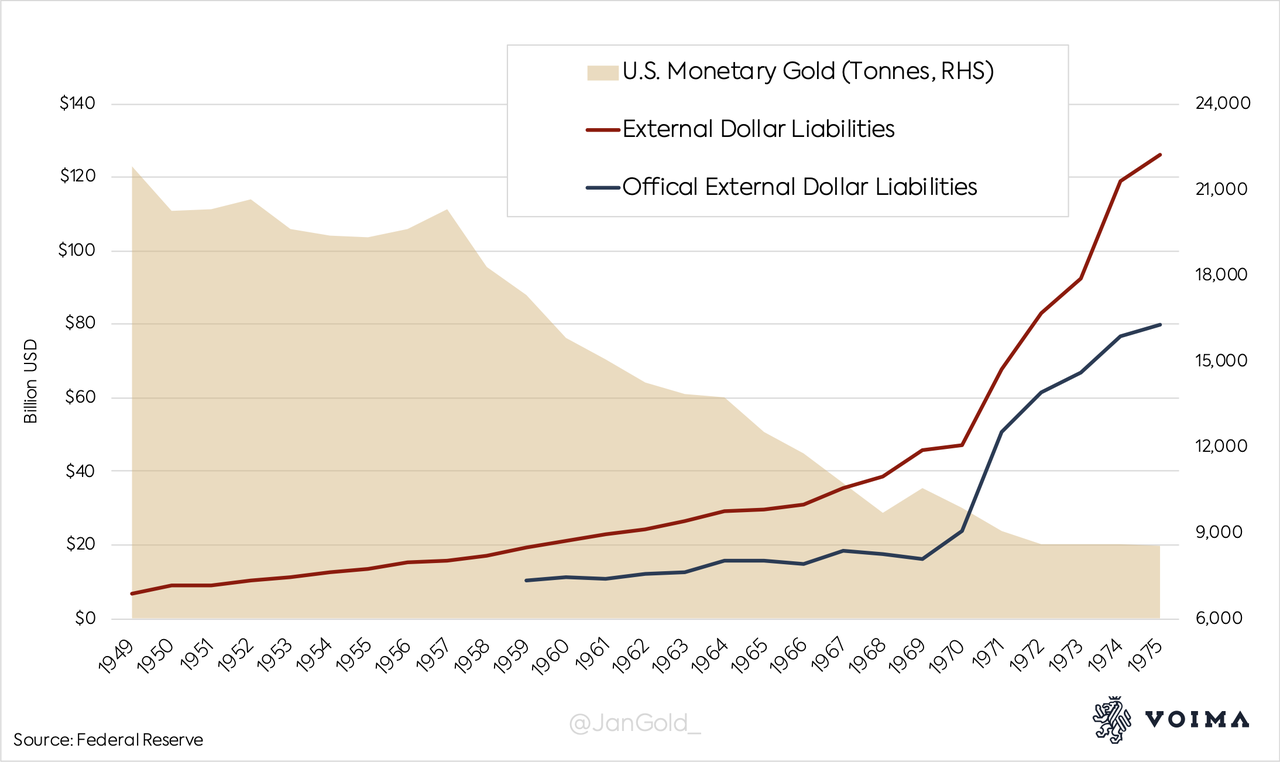

At the end of the Second World War, a new international monetary system called Bretton Woods was ratified. Under Bretton Woods, the U.S. dollar was officially the world reserve currency, backed by gold at a parity of $35 per ounce. The United States owned 60% of all monetary gold—more than 18,000 tonnes—and promised the dollar to be “as good as gold.” All other participating countries committed to peg their currencies to the dollar. Bretton Woods was a typical gold exchange standard.

It didn’t take long for the U.S. to print and export more dollars than it had gold backing them, which raised concern about the parity of $35 dollars per ounce. As a consequence, foreign central banks started redeeming dollars for gold at the U.S. Treasury. The vast gold reserves of the U.S. began flowing out and ended up mainly in Western Europe.

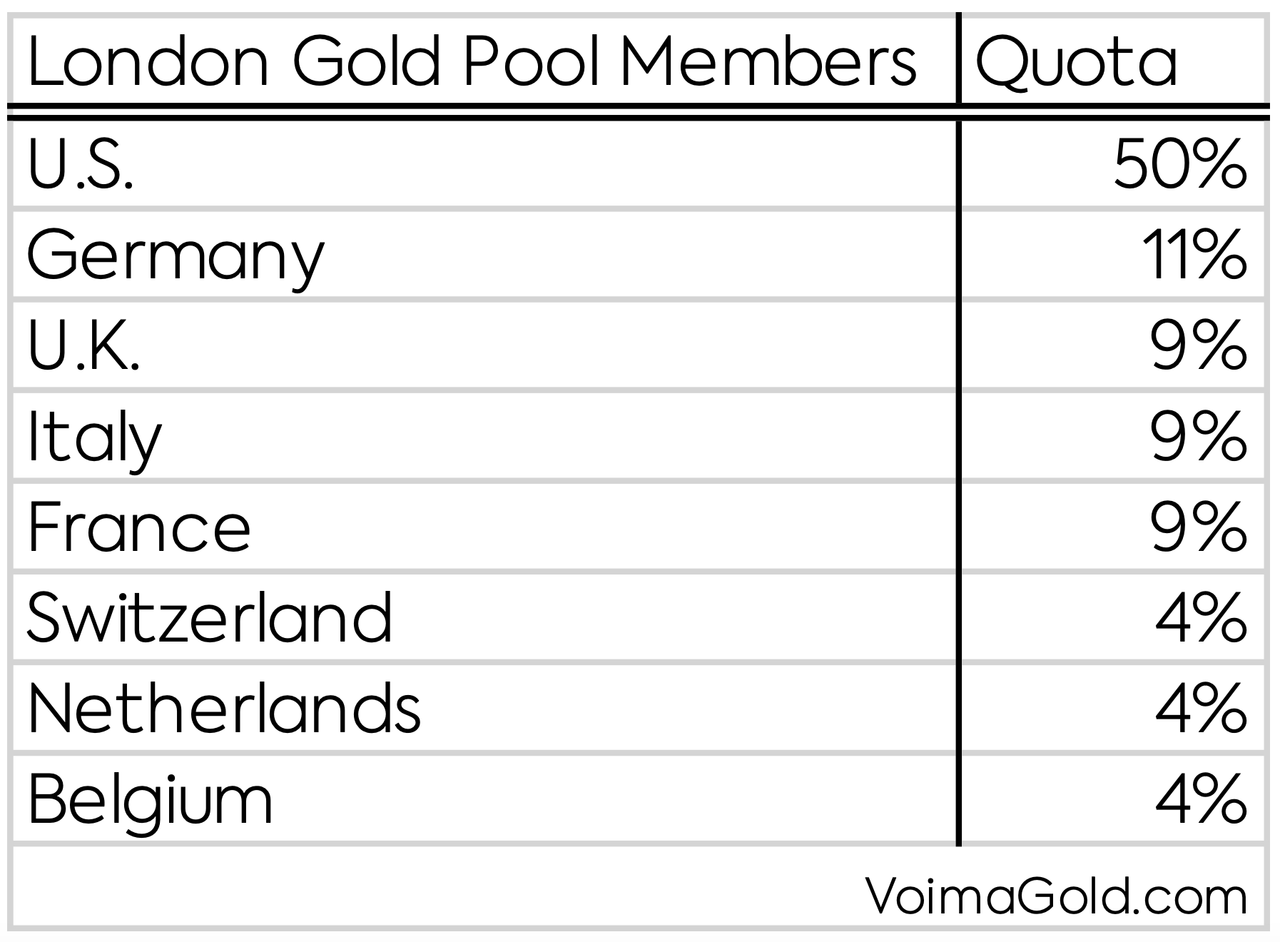

In an attempt to stabilize the international monetary system, a consortium of eight Western central banks set up the London Gold Pool in 1961 to keep the gold price in the free market at $35. Despite being a member of the Pool, France—that was very critical of U.S. monetary policy—repeatedly redeemed dollars at the Treasury. France thus bought gold at the Treasury, to sell in the free market through the Pool.

In 1965 pressure on the dollar increased and the Pool had to supply huge amounts of gold to sustain the peg. European central bankers started deliberating how to get out of the Pool agreement. Europe didn’t want to defend the peg indefinitely for what was in essence a problem caused by the United States. In 1967 the British pound devalued, which injured confidence in the entire system and France withdrew from the Pool. The situation escalated quickly. Famous gold author Timothy Green writes in The New World of Gold (1982):

Could $35 gold be maintained? The gold pool, except for France (under de Gaulle who shrewdly opted out), thought it could. They had nearly twenty-four thousand tons of gold at their disposal. And William McChesney Martin of the Federal Reserve Board rashly said they would defend the $35 price “to the last ingot.” But the Tet offensive in Vietnam crushed that pledge. Between March 8 and March 15, 1968, the pool had to provide nearly one thousand tons to hold the price at the fix. U.S. air force planes rushed more and more Fort Knox gold to London, and so much piled up in the Bank Of England’s weighing room that the floor collapsed.

On March 15, 1968, the Pool ceased its operations and the gold price in the free market was allowed to float. Though central banks agreed to keep trading gold among each other at $35 and not buy and sell in the free market. A “two-tier gold market” had emerged.

Foreign central banks could still redeem dollars at the Treasury—at the official gold price that was lower than the free market price—but it was seen as “unfriendly.” Early August, 1971, France, again, sent a battleship to New York to load up on gold in exchange for dollars. A few days later, on August 15, the United States unilaterally decided to end Bretton Woods by suspending dollar convertibility. Europe, Japan, and other countries, were not amused. Dollar reserves, previously backed by gold, had turned into pieces of paper plummeting in value against gold. What followed was a diplomatic conflict between Europe and the U.S.

Since the 1960s, America seduced foreign central banks to reinvest their dollar reserves in U.S. government bonds (Treasuries), instead of redeeming them for gold. If Treasuries would replace gold in the international monetary system, the United States could continue to print money for imports, and have savers abroad finance their fiscal deficits. Such a dollar standard would yield the U.S. unprecedented power, though it wouldn’t be an equitable system.

One of the reasons the euro was created was to counter dollar dominance. Many decades before it was launched, Western Europe started to integrate. The first seed was the Treaty of Rome in 1957 that gave birth to the European Economic Community (EEC). From classified documents that have been released in recent years, we know the U.S. opposed monetary cooperation in Europe, for the simple reason it didn’t want competition for the dollar hegemony. Below are excerpts from a telephone call between U.S. National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, and Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, William Simon, on March 14, 1973.

Kissinger: … I basically have only one view right now which is to do as much as we can to prevent a united European position without showing our hand. … I don’t think a unified European monetary system is in our interest.

… You understand, my reason’s entirely political, but I got an intelligence report of the discussions in the German Cabinet and when it became clear to me that all our enemies were for the European solution that pretty well decided me.

The “European solution” was to fix the exchange rates of the EEC’s currencies, and float as a bloc against the dollar. The “common float” would enhance trade within Europe and show the world Europe’s unity and leadership. This was not in the interest of the U.S. According to Under Secretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs, Paul Volcker, the European solution was a euphemism for saying: “Let’s leave the United States out of the world and go our independent course.”

Furthermore, the EEC took the stance that central banks should be able to buy and sell gold at a market-related price, both among themselves and on the free market. Also, in 1973 the EEC publicly stated in the New York Times: “[Europe] will promote agreement on international monetary reform to achieve an equitable and durable system taking into account the interests of the developing countries.” This statement can be traced to what Georges Pompidou, President of France, said in a meeting with Richard Nixon, President of the U.S., in 1970: “Power thus established never lasts long. The existence of more centers of economic and political power makes things more complicated but in the longer term has greater advantages.” France’s view was that if there were more centers of economic and political power, the world would be more stable.

The U.S. opposed the end of the two-tier system, because this would increase the official price of gold and put it back in the center of the international monetary system. America pushed for “phasing gold out of the international monetary system,” all the more because Europe was holding more gold than the U.S. since the 1960s.

A historic document that pointedly illustrates the aforementioned dynamics is, “Minutes of Secretary of State Kissinger’s Principals and Regionals Staff Meeting, Washington, April 25, 1974”. From the American meeting in 1974:

Mr. Enders: … It’s been in the newspapers now—the EC [EuropeanCommunity] proposal.

Secretary Kissinger: On what—revaluing their gold?

Mr. Enders: Revaluing their gold—in the individual transaction between the central banks [meaning the end of the two-tier system].

Secretary Kissinger: What’s Arthur Burns’ [Chair of the Federal Reserve] view?

Mr. Enders: Arthur Burns—I talked to him last night on it, and he didn’t define a general view yet. He was unwilling to do so. He said he wanted to look more closely on the proposal. Henry Wallich, the international affairs man, this morning indicated he would probably adopt the traditional position that we should be for phasing gold out of the international monetary system; but he wanted to have another look at it.

Secretary Kissinger: … my understanding of this proposal would be that they—by opening it up to other countries, they’re in effect putting gold back into the system at a higher price.

Mr. Enders: Correct.

Secretary Kissinger: Now, that’s what we have consistently opposed.

Mr. Enders: Yes, we have. You have convertibility if they—

Secretary Kissinger: Yes.

Mr. Enders: Both parties have to agree to this. But it slides towards and would result, within two or three years, in putting gold back into the centerpiece of the system—one. Two—at a much higher price. Three—at a price that could be determined by a few central bankers in deals among themselves.

…

Secretary Kissinger: Why are we so eager to get gold out of the system?

Mr. Enders: It’s against our interest to have gold in the system because for it to remain there it would result in it being evaluated periodically. Although we have still some substantial gold holdings—about 11 billion [USD]—a larger part of the official gold in the world is concentrated in Western Europe. This gives them the dominant position in world reserves and the dominant means of creating reserves. We’ve been trying to get away from that into a system in which we can control—

Secretary Kissinger: But that’s a balance of payments problem.

Mr. Enders: Yes, but it’s a question of who has the most leverage internationally. If they have the reserve-creating instrument, by having the largest amount of gold and the ability to change its price periodically, they have a position relative to ours of considerable power.

…

Secretary Kissinger: O.K. My instinct is to oppose it. What’s your view, … Ken?

[Ken] Rush: Well, I think probably I do. The question is: Suppose they go ahead on their own anyway. What then?

Secretary Kissinger: We’ll bust them.

Mr. Enders: I think we should look very hard then, Ken, at very substantial sales of gold—U.S. gold on the market—to raid the gold market once and for all.

The above goes to show the distaste of the U.S. with respect to gold, and their ambition to maintain the dollar hegemony.

For informative comments by Arthur Burns we will turn to a “Memorandum For The President” he wrote on June, 3, 1975. From Burns:

… removal of the present restraints on inter-governmental gold transactions and on official purchases from the private market [meaning the end of the two-tier system] could well release forces and induce actions that would increase the relative importance of gold in the monetary system. In fact, there are reasons for believing that the French, with some support from one or two smaller countries, are seeking such an outcome.

…

It is an open secret among central bankers that, at a later date, the French and some others may well want to stabilize the market [gold] price within some range.

All in all, I am convinced that by far the best position for us to take at this time is to resist arrangements that provide wide latitude for central banks and governments to purchase gold at a market-related price.

The French, and some of its allies, wanted gold’s importance to increase in the international monetary system and stabilize its price “at a later date.” Which boils down to a gold standard. The Federal Reserve favored a continuation of the two-tier market, which in practice meant gold’s demonetization.

Right after the two-tier system was cancelled in 1978, eight European countries launched the European Monetary System (EMS). We will leave the exact mechanics of the EMS for a future article, but I will share a quote by Professor of American and Foreign Law, Kenneth W. Dam, with respect to the EMS. From The Rules of the Game: Reform and Evolution in the International Monetary System (1982):

Finally, the EMS may also turn out to be a first step toward rehabilitating gold as an integral part of the international monetary system.

In 1998 the EMS was annulled and replaced by the Eurosystem.

Although France, and some other European countries, were surely in favor of gold and against the dollar hegemony in the 1970s, I don’t know if this group had a solid plan from the start. Perhaps, they had a direction in mind and adjusted their policies throughout the years.

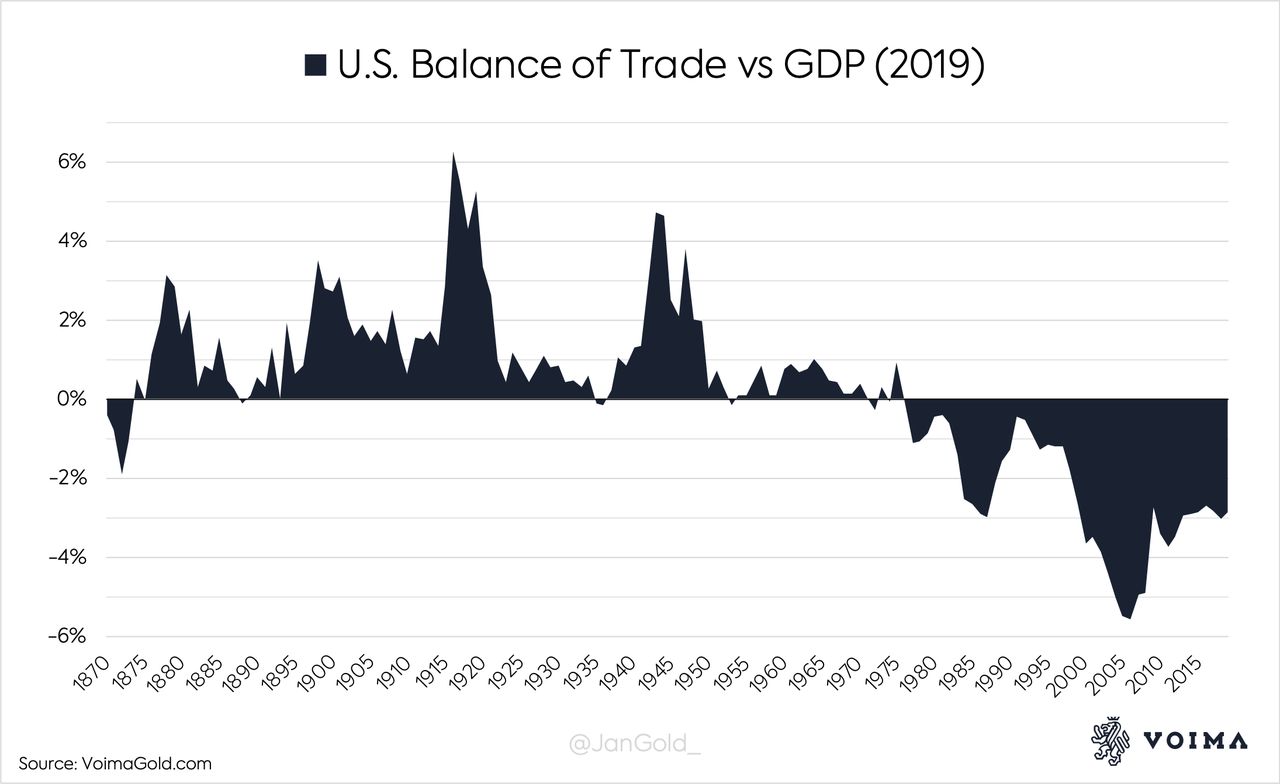

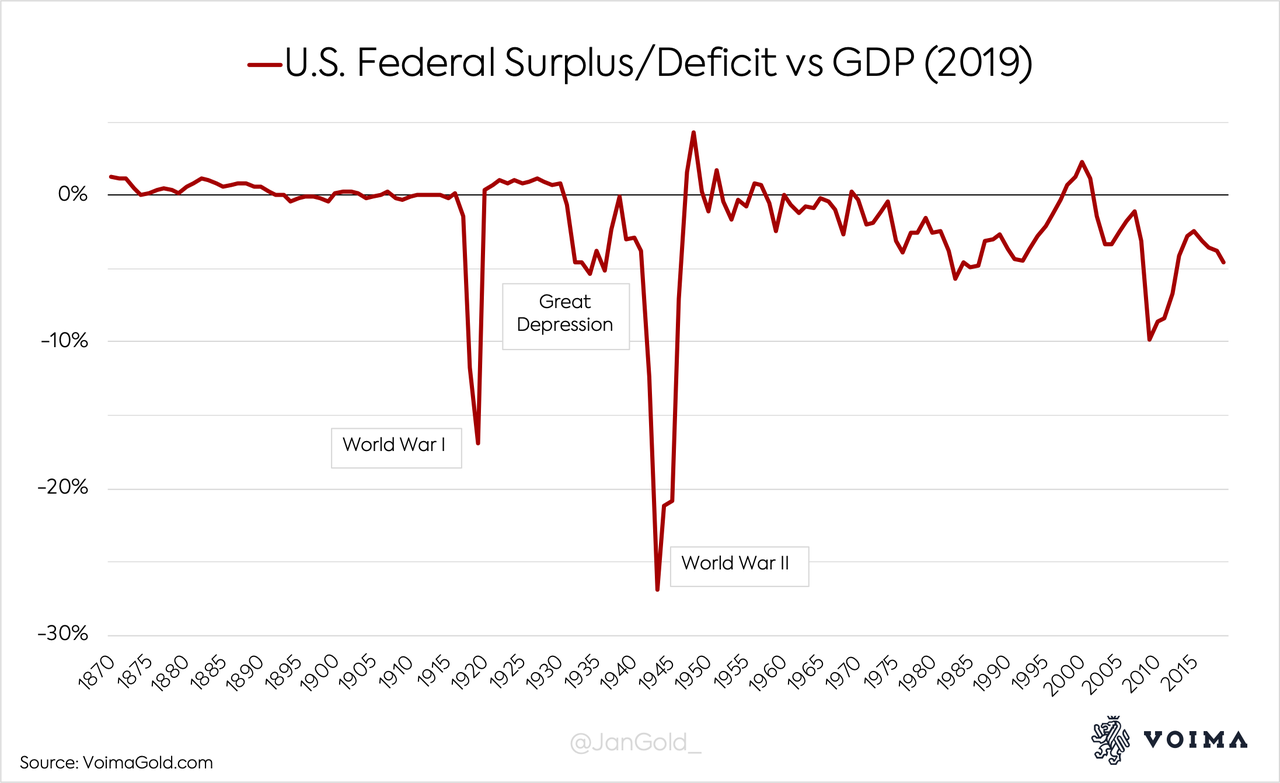

The U.S. never did “raid the gold market once and for all.” They sold roughly 500 tonnes in the late 1970s and 1980s in an attempt to lower the price in the free market. Gold traded more or less sideways throughout in the 1980s and 1990s, but didn’t get phased out of the international monetary system. However, the Americans succeeded in imposing the paper dollar standard on the world. There was a lot of discussion in the 1970s about the Special Drawing Right (SDR), a reserve asset issued by the International Monetary Fund, but it didn’t function (and still doesn’t). The U.S. could continue to print and export dollars, and Treasuries became the main international reserve asset. As a result, the U.S. has been running a trade and fiscal deficit since 1971.

Europe Equalizes Gold Reserves Internationally

As mentioned, Europe preferred a new “equitable and durable system taking into account the interests of the developing countries,” and France, supported by allies, was aiming for something of a gold standard “at a later date.” Remarkably, what I discovered is that European central banks started selling gold in the 1990s to equalize their gold reserves relative to other nations. A new gold standard would be equitable if all gold was distributed evenly, which is what European central banks have been managing.

After the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, the Minister of Finance of the Netherlands, Jan Kees de Jager, was asked in parliament for the main reason why the Dutch central bank had sold 1,100 tonnes of gold since 1993, and if storage costs had been a motivation. His answer:

Through gold sales in the past, the Dutch central bank brought its relative gold holdings more in line with other important gold holding nations. Storage costs didn’t play any part in the decision to sell gold…

At the time DNB [Dutch central bank] determined that from an international perspective it owned a lot of gold proportionally.

Another question directed at de Jager, was if he could confirm if other nations—in contrast to the Netherlands—had increased their official gold reserves in the past years. His answer:

The buyers are developing nations whose international reserves are growing, or historically have a small gold stock.

According to de Jager, the Dutch central bank sold gold to equalize reserves internationally. He mentioned no other reason for the sales. (De Jager denied the Dutch central bank sold gold for paying off the national debt of the Netherlands, which is a frequently mentioned reason for European gold sales.) In addition, Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad reported in 1993 that the Dutch central bank had sold 400 tonnes through the Bank for International Settlement, and this was partially bought by the Chinese central bank. I conclude that the Netherlands sold 1,100 tonnes to help developing nations get equal in terms of gold reserves proportionally and prepare for a new monetary system that incorporates gold. Why else—than to reposition gold in the international monetary system—would the Netherlands want to equalize their gold reserves with other “important gold holding nations”?

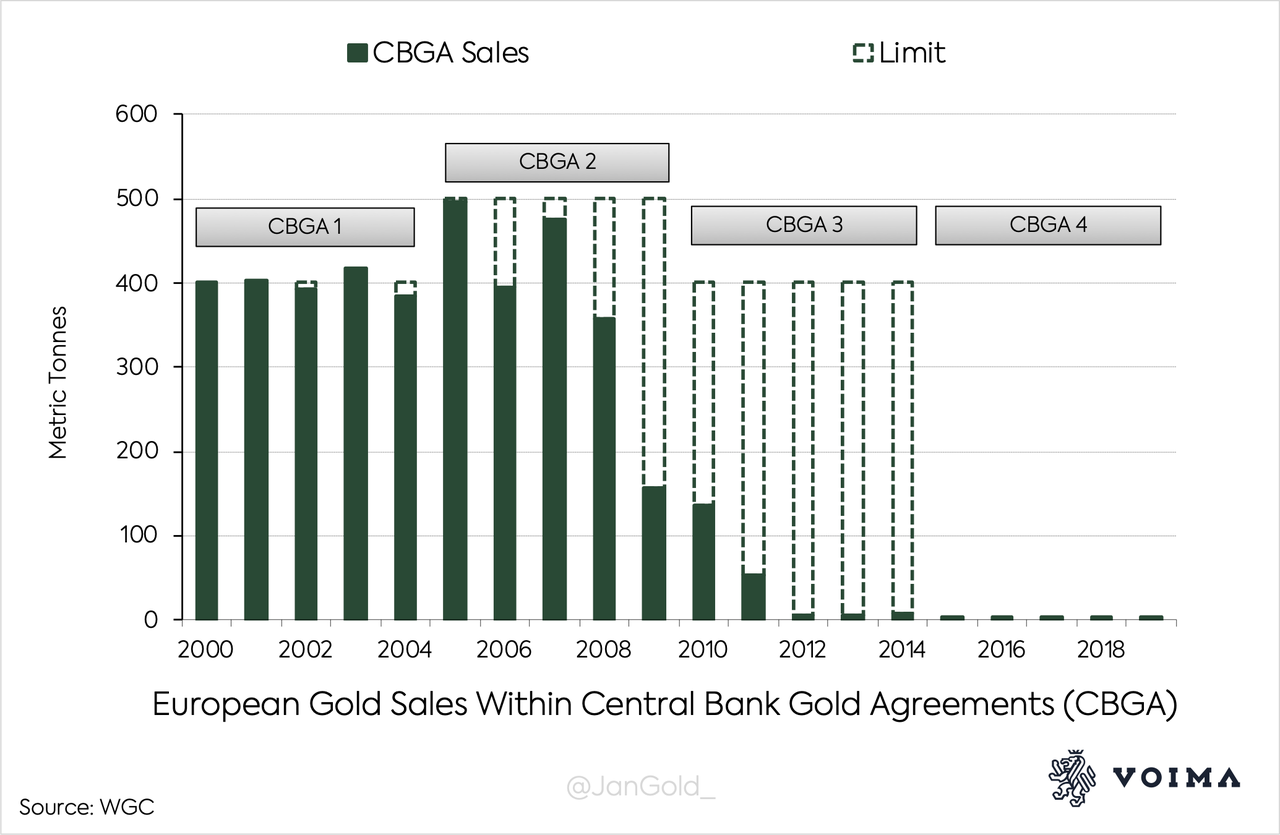

Other central banks in Europe have done the same as the Dutch central bank. In 1999, fourteen (Western) European central banks surprised the gold market with a statement regarding a “concerted programme of [gold] sales over the next five years.” The program was dubbed the Central Bank Gold Agreements (CBGA), and the signatories declared:

Gold will remain an important element of global monetary reserves. … Annual [aggregated] sales will not exceed approximately 400 tons and total sales over this period will not exceed 2,000 tons. … This agreement will be reviewed after five years.

Gold sales were tightly coordinated. In the knowledge Europe wanted to balance gold reserves internationally (more proof below) this statement makes perfect sense.

The World Gold Council interpreted CBGA as removing “concern that uncoordinated central bank gold sales were destabilising the market, driving the gold price sharply down.” It’s true that some European countries sold significant amounts of gold before CBGA, which drove the price down, and right after CBGA was announced the gold price started to rise. Mission accomplished, I would say.

Eventually, CBGA was extended three times, and ten more European countries joined. During CBGA 1-4 a little over 4,000 tonnes were sold, virtually all of which before 2009.

One of the members of Voima Gold’s Advisory Board is Pentti Pikkarainen, who was Head of Banking Operations at the central bank of Finland—one of the signatories of CBGA—from 2001 until 2010. When I asked Pikkarainen if in addition to the Dutch central bank, others had sold to bring their “relative gold holdings more in line with other important gold holding nations” as well, he answered:

It is true that some central banks compared their gold holdings with those of other central banks and came to that type of conclusion.

So, multiple central banks in Europe sold gold to equalize reserves internationally.

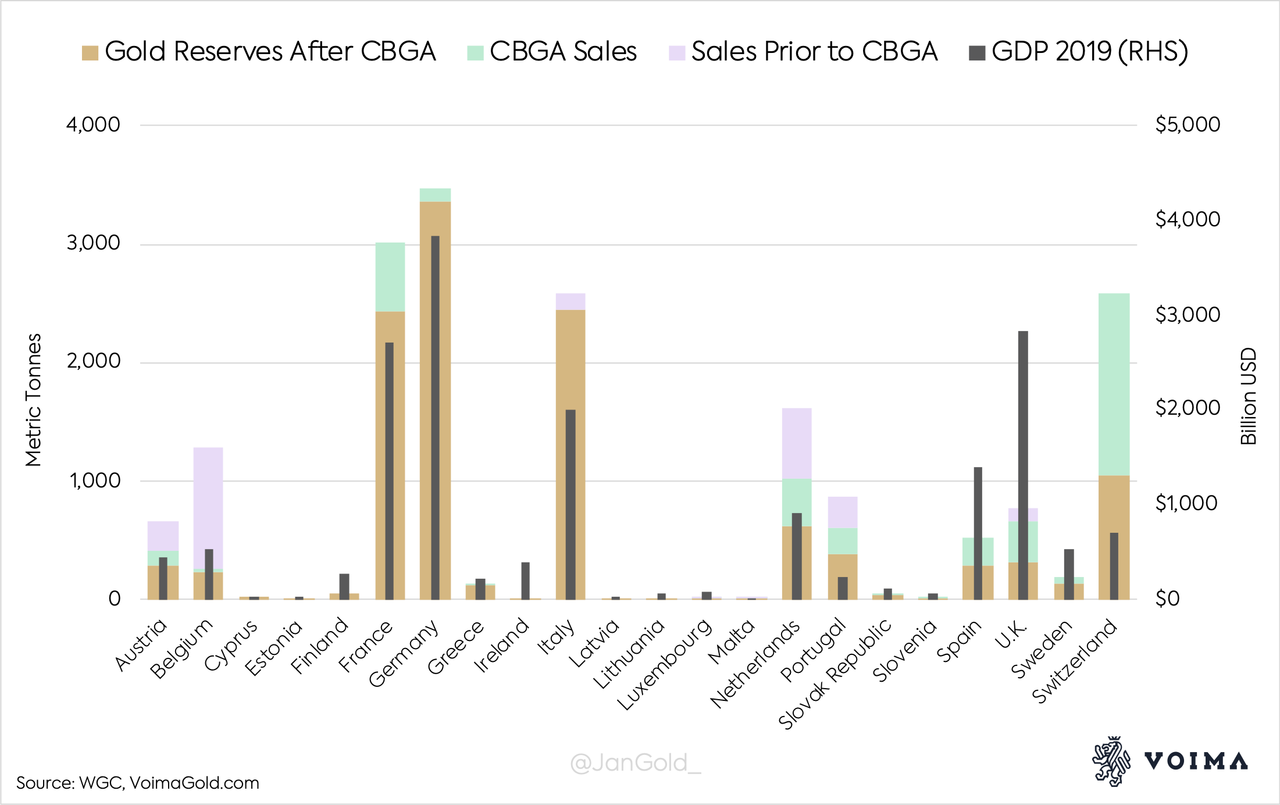

To get a sense of the equalization process within Europe, I have made a chart showing gold sales per country before and during CBGA, current gold reserves, and Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Before and during CBGA, mainly medium sized economies sold gold to have an equal share relative to others. It’s not a perfect fit, but striking nonetheless. Still more, because Cyprus, Estonia, Italy, and Lithuania were signatories of CBGA, but didn’t sell an ounce of gold during the “concerted programme of sales.” Finland and Ireland were buyers during CBGA, albeit of small weights, which makes sense when comparing reserves across the board. It appears CBGA was not a concerted programme of gold sales, but a concerted programme of equalizing gold reserves. The main outlier is the U.K.

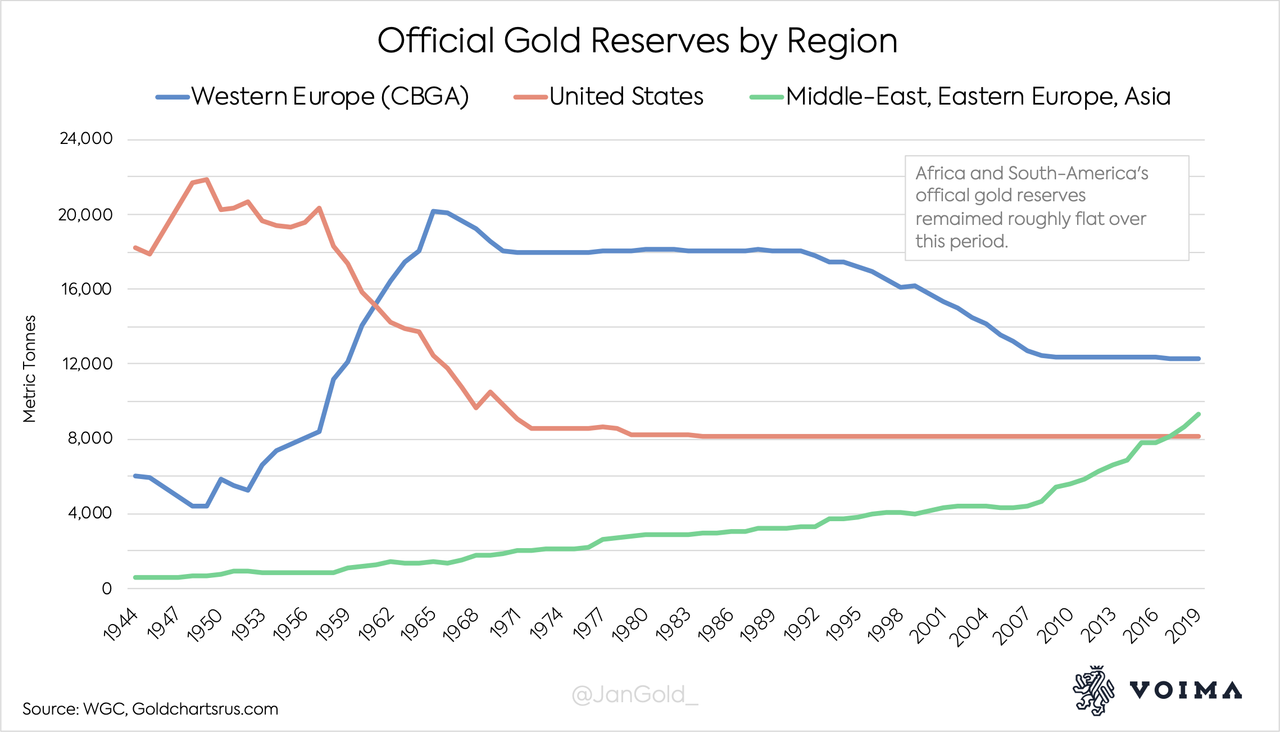

Official gold reserves around the world are spread more evenly since the 1970s. Eurasia minus Western Europe held 2,000 tonnes in 1971, versus 9,300 tonnes currently.

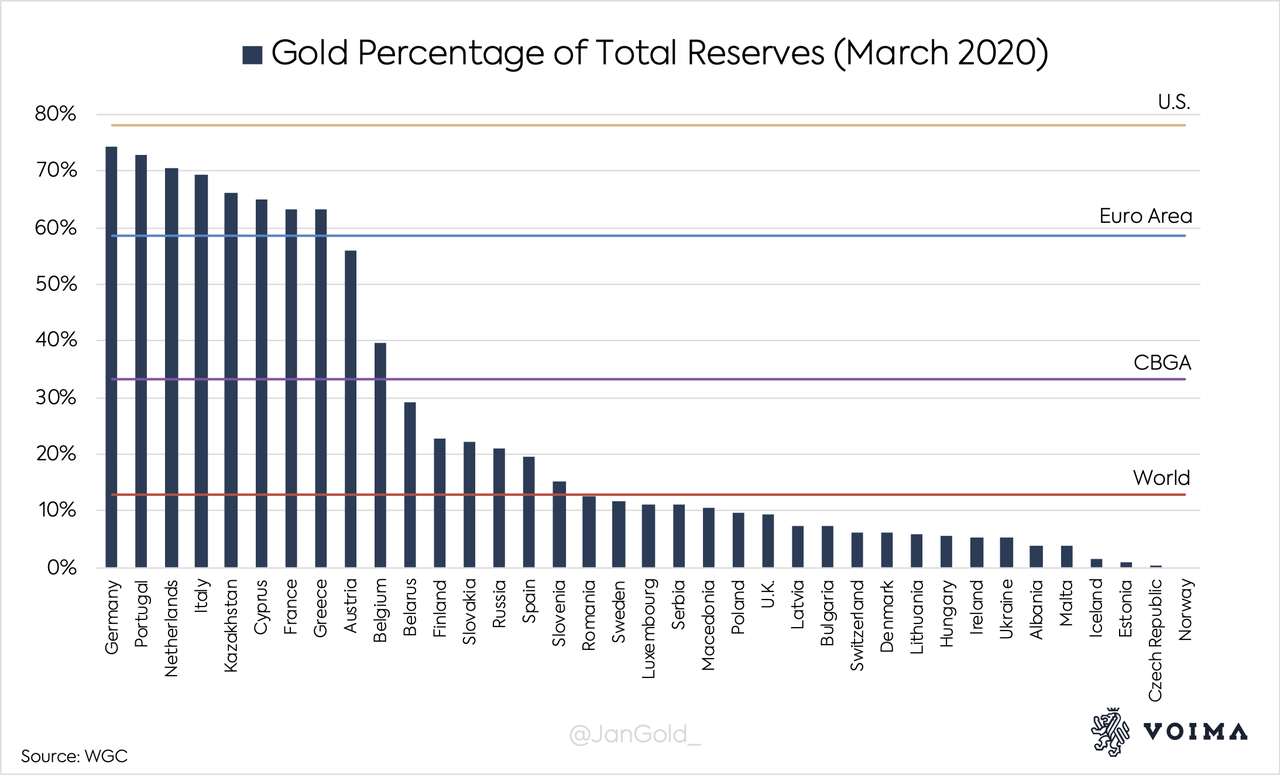

The equalization process continues until this day. In 2018, the central bank of Hungary (MNB) purchased 31.5 tonnes of gold, a tenfold in their official reserves. MNB disclosed it bought gold because “it may play a stabilising role … in times of structural changes in the international financial system,” but also to bring their gold reserves more in line to its peers. The Polish central bank (NBP) bought 125.7 tonnes in 2019 and stated the same:

the share of gold in NBP foreign exchange reserves was below the average for all central banks (10.5%) and significantly below the average in European countries (20.5%). The purchase of gold allowed not only to increase the strategic financial buffer of the country, but also to bring the NBP closer in terms of the share of gold in foreign exchange reserves to the average of all central banks (10.5%).

We undoubtedly read about preparing for a change in the international financial system, and balancing gold reserves proportionally. I’m aware de Jager, MNB, and NBP talk about leveling “gold reserves as a percentage of total reserves,” but I see a more significant pattern in gold reserves versus GDP. To be complete, below is a chart showing official gold reserves as a percentage of total reserves (foreign exchange, gold, and SDRs) for European countries.

Private Gold Ownership Distribution

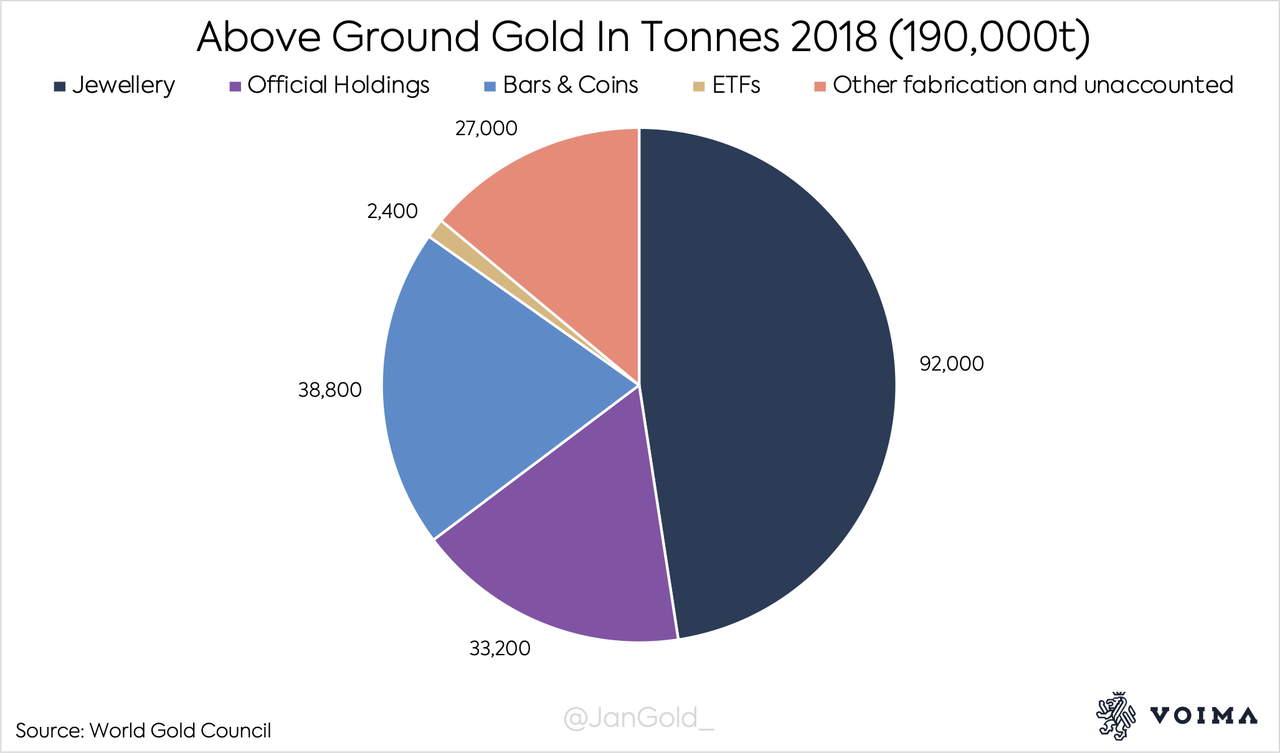

Private gold holdings make up a larger portion of total above ground stocks than official holdings, but it’s a lot harder to localize. Although the data is limited, private gold distribution shows to be roughly equal for “important gold holding nations.” (Of course, it can never be exactly equal.)

When the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took control over China in 1949 it effectively banned the private use of gold. Since the 1980s, Chinese citizens were slowly allowed to buy gold jewelry, and in 2002 the Chinese gold market was fully liberalized with the launch of the Shanghai Gold Exchange. Gradually, the CCP began stimulating its citizens to accumulate gold. In 2012, President of the China Gold Association, Sun Zhaoxue, elaborated on the importance of private gold ownership in the leading academic journal of the CCP’s Central Committee, Qiushi:

Practice shows that gold possession by citizens is an effective supplement to national reserves and is very important to national financial security. … We should advocate to ‘store gold among the people’ …

A year later Sun made a statement in the Wall Street Journal on how much gold Chinese people own on average:

Meanwhile, the average Chinese person “only holds 4.5gram of gold,” Mr. Sun said. “That is far below an average of 24 grams per person globally …

The Chinese government aims to elevate the amount of private gold per capita, to bring it more in line to the global average. China’s gold strategy matches Europe’s gold strategy in terms of equalizing reserves (next to the obvious reasons to own gold in the first place).

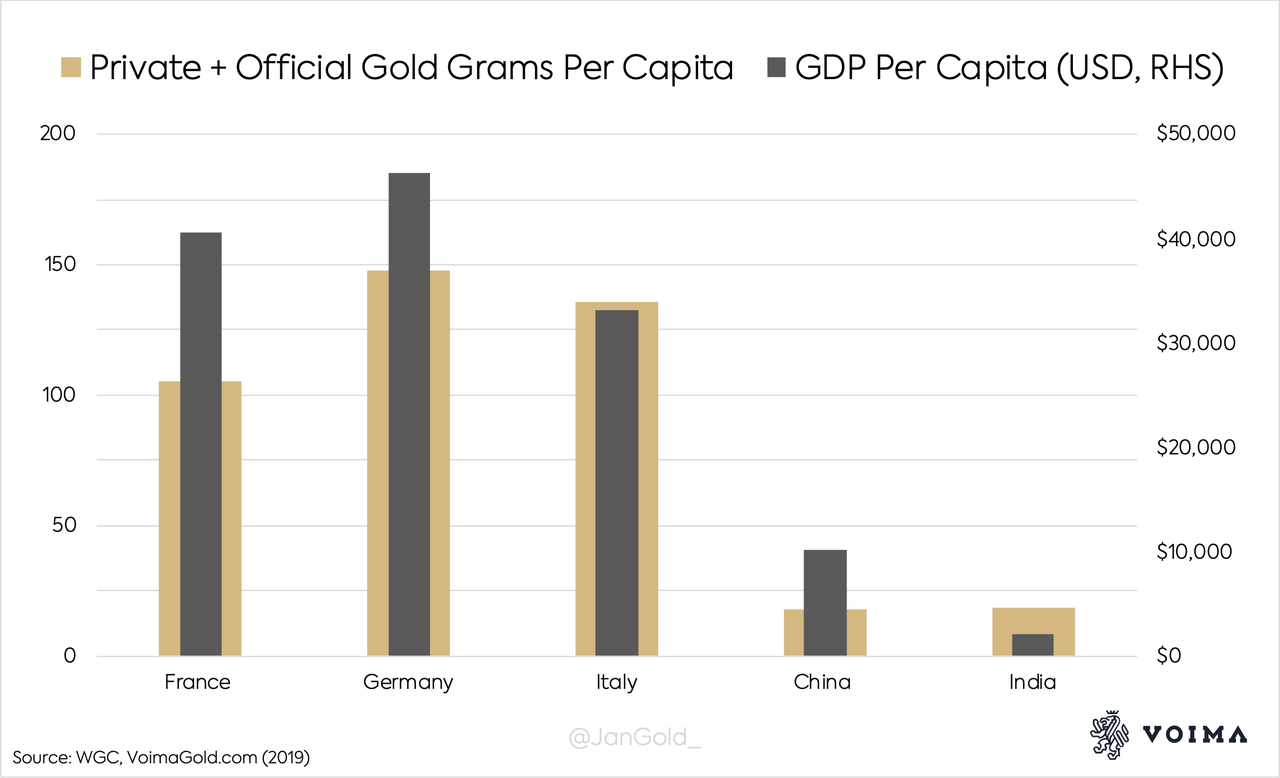

From previous research, I know approximately how much private gold is in India, China, France, Italy, and Germany. When I combine the private and official gold reserves of these countries, and compare it to GDP per capita, these measures appear to be quite close to each other.

The amount of gold each citizen owns on average, directly and via their central bank, is roughly equal to their economic income. At a gold price of about $10,000 dollars per ounce, that is. The biggest difference is between China and India.

It goes without saying that partially the gold distribution in recent decades has been organic.

The story of China and gold goes back further than many people think. On the website of Bank of China—a state owned bank—we can read:

From 1973 to 1974, Vice Premier Chen Yun … carried out special research on foreign trade issues. On June 7, 1973, when listening to a bank report, Vice Premier Chen Yun raised ten important questions in international economy and finance, … The ten research topics assigned by Chen Yun covered economy, finance, currency and other important aspects in the contemporary capitalist world, which were:

(1) How much money was issued in the U.S., Japan, UK, Federal Republic of Germany and France from 1969 to 1973? How much were their foreign currency reserves and gold reserves?

…

(6) In addition to political contradictions, what are the economic contradictions between the U.S. and UK, Japan, Federal Republic of Germany and France? What are the principal contradictions?

(7) What are the possible solutions to problems concerning trade and currency between the U.S. and Japan, UK, France and Federal Republic of Germany? Finance Minister Valery Giscard d’Estaing of France advocated the linkage between currency and gold. Can we reckon an approximate ratio between the total monetary flow and the total possession of gold in the world?

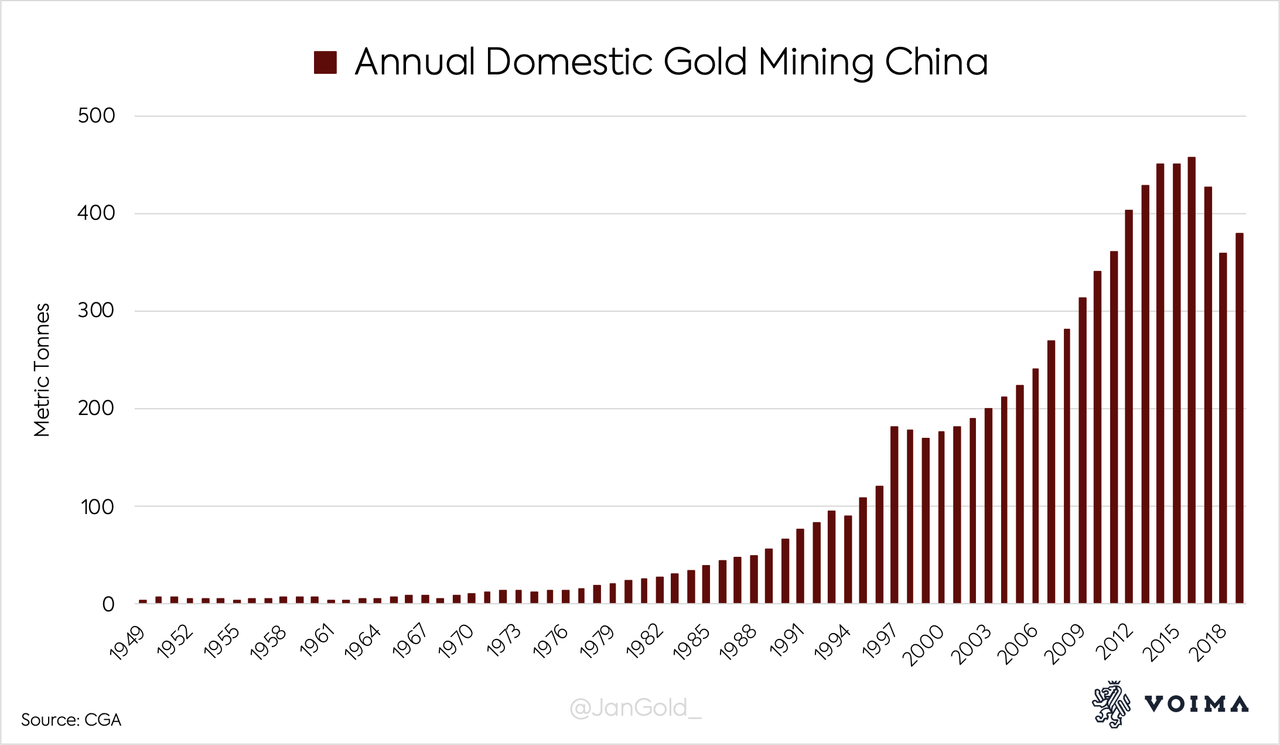

I don’t think it’s a coincidence the Chinese government started developing domestic gold mining in the 1970s, and is now the nation with the largest mine output. Don’t get me wrong, the Chinese didn’t become “gold bugs” overnight, but understood the strategic importance of gold. They anticipated gold’s role in international finance would anything but vanish, as the U.S. wanted the world to believe in the 1970s.

In 1979, the Chinese even set up a new military unit, called the Gold Armed Police, dedicated to gold exploration. This division of the Chinese army still exists.

Setting the Stage for a Gold Standard

After the GFC, Germany, the Netherlands, Hungary, Poland, Turkey, and Austria have repatriated gold from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and Bank of England. These countries show to assign greater importance to gold as a reserve asset versus fiat currencies, and their trust in the U.S. and U.K. as custodians has waned. In the words of the Polish central bank:

central banks usually strive to diversify their gold storage locations, … to limit geopolitical risk, the consequence of which could be, for example, loss of access or limitation of the free disposal of gold reserves kept abroad.

Storing gold on domestic soil is safer than abroad, but having some of it in trading hubs such as London allows the gold to be used more easily for, i.e., swaps and international settlement. According to the German central bank their repatriation scheme had three objectives: cost efficiency, security, and liquidity.

Another important indicator for what European countries have prepared for, is that after the GFC some have upgraded their official gold reserves to current wholesale industry standards. France, Germany, Sweden, and Poland, that we know of, have disclosed their gold bars to adhere to “London Good Delivery” standards. Consequently, their metal is liquid and ready for international settlement.

From the Banque de France:

Since 2009, the Banque de France has been engaged in an ambitious programme to upgrade the quality of its gold reserves. The target is to ensure that all its bars comply with LBMA [London Bullion MarketAssociation] standards so that they can be traded on an international market.

Europe is well prepared for a gold standard. The U.S. less so, because most of its gold does not comply to prevailing industry standards. Thereby, the audits of the U.S. official gold reserves have been executed with an “inadequate degree of integrity.”

Last but not least, after the GFC European central banks have started communicating gold’s unparalleled stable properties, and promote gold ownership. The French central banks states on its website gold is “the ultimate store of value.” According to the President of the German central bank, Jens Weidmann, gold is “the bedrock of stability for the international monetary system.” On the website of the central bank of Italy it reads:

Gold is an excellent hedge against adversity. … Another good reason for holding a large position in gold is as protection against high inflation since gold tends to keep its value over time. Moreover, unlike foreign currencies, gold cannot depreciate or be devalued …

Gold … is not an asset ‘issued’ by a government or a central bank and so does not depend on the issuer’s solvency.

The Dutch central bank states on its website:

A bar of gold always retains its value …

Gold is the perfect piggy bank—it’s the anchor of trust for the financial system. If the system collapses, the gold stock can serve as a basis to build it up again.

Let this sink in. These are central banks that issue their own currency, and are solely tasked to ensure economic stability. Yet, they openly state gold is superior to the currency they issue and advice people to own gold as protection against “high inflation,” “adversity,” and the possibility “the system collapses.” If fiat currencies would be safer than gold, these central banks wouldn’t recommend people to own gold as “the perfect piggy bank.” But they do recommend people to own gold, because, ironically, gold “is not an asset ‘issued’ by a government or a central bank and so does not depend on the issuer’s solvency.” European central banks are confessing their own paper money system is failing. They can’t say this explicitly because it would cause instant panic in financial markets, but how much more obvious can they make it?

In my opinion, these central banks are alluding to a new monetary system based on gold.

Conclusion

We have established that since the 1970s Europe has been countering the dollar hegemony and wanted gold back in the center of a new “equitable and durable system taking into account the interests of the developing countries.” Subsequently, they have equalized official gold reserves internationally, strategically allocated their gold, upgraded their gold to current industry standards, and are now promoting gold as the “perfect piggybank” and as “protection against high inflation.”

The trend in Asia is also increasingly against dollar dominance and in favor of gold. In May, 2019, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad mooted the idea of a new international currency pegged to gold. Reuters reported in April, 2020, that the “president of the Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE) called for a new super-sovereign currency to offset the global dominance of the U.S. dollar, which he predicted would decline long term, while gold prices rally.” The President of the SGE also said: “The global clout of the United States will reduce, while the status of the European Union and China will rise in global affairs.”

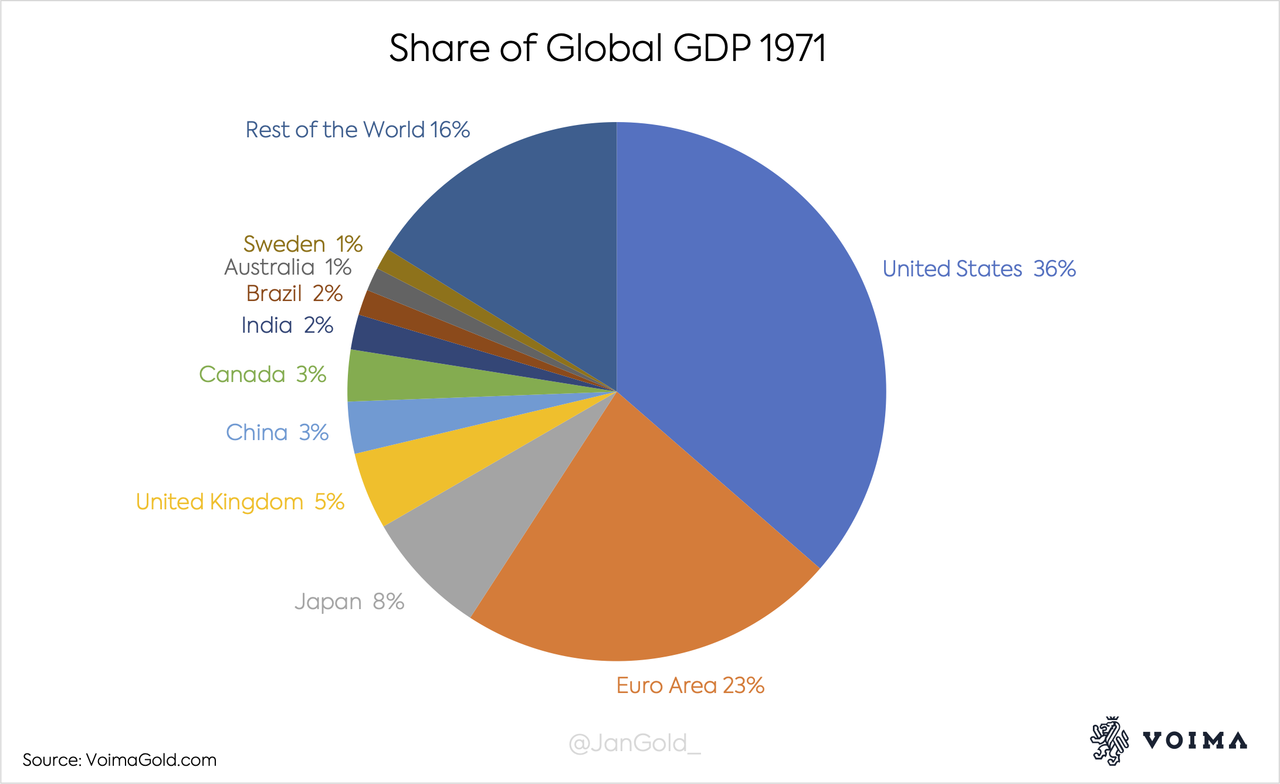

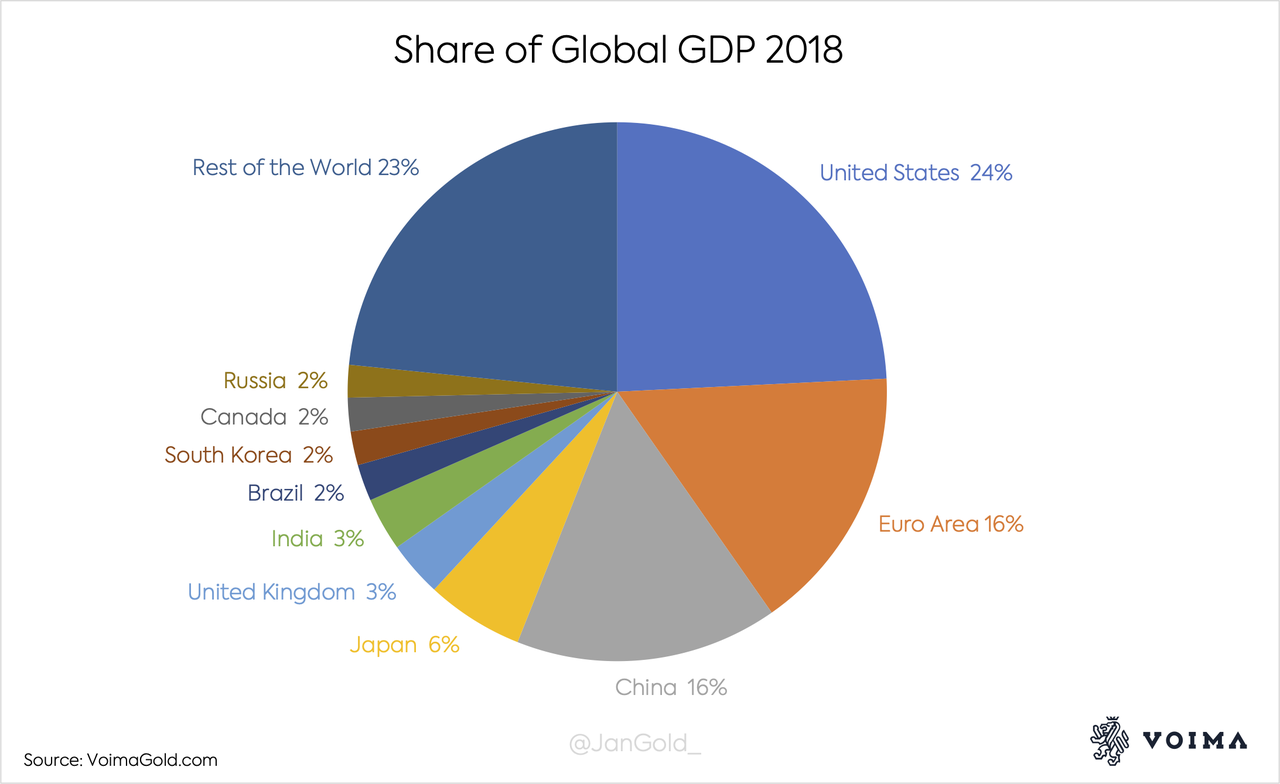

In line with the long-term trend discussed above is that economic strength is more equal than it was in 1971. Fifty years ago, the U.S. and Western Europe (Euro Area) accounted for 59% of global GDP; currently their share is 40%. This rhymes with Pompidou’s remark on “the existence of more centers of economic and political power makes things more complicated but in the longer term has greater advantages.”

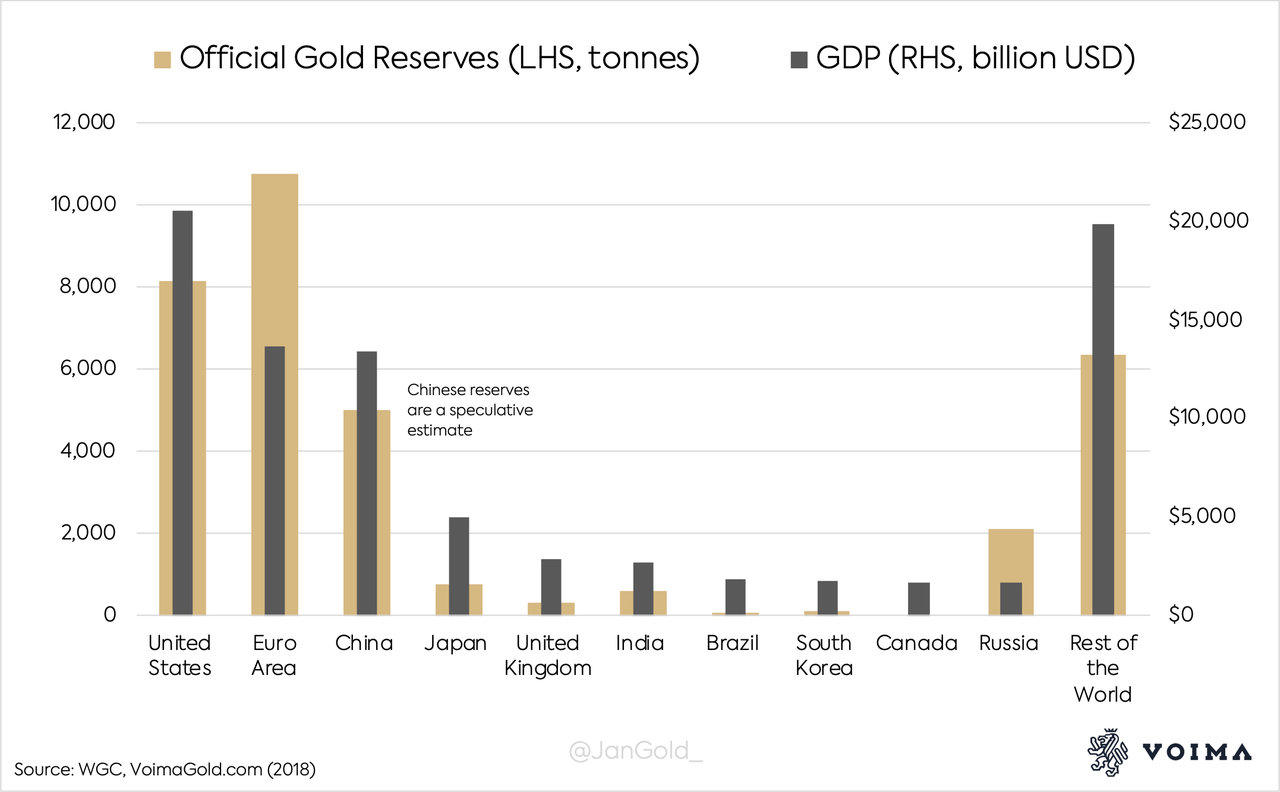

Stunningly, economic strength of the largest power blocks—the U.S., China, Euro Area, and Russia—is roughly in line with their relative official gold reserves, as you can see in the chart below. For China’s official gold reserves I have used a speculative estimate of 5,000 tonnes (in this post I explain how I have computed this number).

The importance of the chart above can be confirmed by an American memo dating from 1974. Sidney Weintraub, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for International Finance and Development, wrote to Paul Volcker regarding the gold issue that “the distribution of … world [gold] reserves would be highly inequitable, with eight wealthy countries getting three-fourths, while the developing countries would get less than 10 percent.” The Europeans thought about this problem, and they helped solving it by equalizing gold reserves internationally.

The essence of the chart is that economic output (GDP) is real, and gold is too. When fiat currencies are devalued to alleviate the global debt burden, gold and GDP distribution won’t change much, which is beneficial for a shift towards an equitable gold standard.

Likely, Japan and the U.K. have been pressured by the U.S. not to increase their gold reserves. In The Prospect for Gold: The View to the Year 2000 (1987) Timothy Green writes: “For many years the Bank of Japan, wishing to keep well with the US Treasury, deliberately avoided buying gold.” Japan’s official gold reserves have been flat since 1978, while it’s the largest foreign holder of Treasuries. India, Brazil and South Korea have all bought gold after the GFC. Why Canada has zero gold is beyond me, but it can be related to the fact that they have a lot of in-ground reserves.

Although it’s clear that Europe and other nations are prepared for a new monetary system that incorporates gold, it’s unknown how this system will look like. It can be similar to the classic gold standard, or it can be a new model. We will dive into the economics of this in a future article. In any case, I think that gold will get a prominent role in a forthcoming system. Needless to say, in such a scenario the nominal gold price will be significantly higher from where it trades today.

As we are currently witnessing, a monetary system without an anchor is bound to fail, and what anchor is more suitable than gold? Gold is internationally the most evenly spread financial asset without counterparty risk and its stability has a proven track record of 5,000 years.

There hasn’t been a lack of signals from Europe and “developing nations” for a monetary reset. Let me finish with an example from 2014. Cheng Siwei, chairman of the International FinancialForum (IFF), said at an IFF conference: “The world today is facing a revolution. It is imperative to construct a new global financial framework and to formulate new rules.” On the same conference Jean-Claude Trichet, former President of the European Central Bank and co-chairman of the IFF, stated: “The global economy and global finance is at a turning point, … new rules have been discussed not only inside the advanced economies, but with all emerging economies, including the most important emerging economies, namely, China.”

These statements are compatible with the international movement towards gold that keen observers will have noticed.

Sources (Books, Papers, and Articles):

- Bank of China, 1973. Punctual Delivery of Ten Research Topics Assigned by Vice Premier Chen Yun. (link)

- Bordo, M., Monnet, E., and Naef, A. 2017. The Gold Pool (1961-1968) And the Fall of The Bretton Woods System. Lessons for Central Bank Cooperation. (link)

- China Daily, November 5, 2014. Reform of World Financial Order Needs Strategic Thinking. (link)

- The China Times. Mysterious Gold Exploration Unit of People’s Armed Police. (link)

- Dam, K. D. 1982. The Rules of the Game: Reform and Evolution in the International Monetary System.

- Financial Express, May 20, 2019. In Gold We Trust: India’s Household Gold Reserves Valued at Over 40% of GDP. (link)

- Green, T. 1982. The New World of Gold.

- Green, T. 1987. The Prospect for Gold: The View to the Year 2000.

- Grabbe, J. O. 1998. Gold Market. (link)

- Jansen, K. July 20, 2017. PBOC Gold Purchases: Separating Facts from Speculation. (link)

- Mundell, R. A. 1997. The International Monetary System in the 21st Century: Could Gold Make a Comeback? (link)

- Nieuwenhuijs, J. November 25, 2019. German Central Bank: Gold Is the Bedrock of Stability for the International Monetary System. (link)

- Nieuwenhuijs, J. December 17, 2019. US Official Gold Reserves Auditor Caught Lying. (link)

- Nieuwenhuijs, J. January 15, 2020. China’s Gold Hoarding: Will It Cause the Price of Gold to Rise? (link)

- Nieuwenhuijs, J. February 28, 2020. What Is an SDR and Will It Be the Next World Reserve Currency? (link)

- Nieuwenhuijs, J. April 2, 2020. Germany Hoarding Gold to Prepare for Currency Reform, Italy Dishoards. (link)

- Nieuwenhuijs, J. June 24, 2020. Why Gold, and Why Now. (link)

- NewYork Times, September 27, 1972. Text of Shultz Talk Before International Monetary Fund and World Bank. (link)

- New York Times, September 24, 1973. Text of the European Economic Community’s Proposal on Relations With U.S. (link)

- Thiele, C. L. 2018. Germany’s Gold.

- Trachtenberg, M. 2010. The French Factor in U.S. Foreign Policy during the Nixon-Pompidou Period, 1969-1974. (link)

- Rueff, J. 1972. The Monetary Sin of the West. (link)

- Reuters, May 30, 2019. Malaysia’s Mahathir Proposes Common East Asia Currency Pegged to Gold. (link)

- Reuters, April 28, 2020. Shanghai Gold Boss Wants Super-Sovereign Currency for Post-Crisis Times. (link)

- Sun, Zhaoxue, August 1, 2012. Build a Secure Barrier for My Country’s Economy and Finance. (link)

- Wall Street Journal, June 30, 2013. Gold Standard? China Doesn’t Set It. (link)

Sources (Others):

- Answers from Minister of Finance de Jager inDutch parliament, September 19, 2011. Antwoorden van de minister van Financiën op de vragen van het lid E. Irrgang (SP) over de goudvoorraad (kenmerk 2011Z17888, ingezonden 19 september2011). (link)

- Burns, A. June, 3, 1975. Memorandum For The President. (link)

- FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1969–1976,VOLUME XXIV, MIDDLE EAST REGION AND ARABIAN PENINSULA, 1969–1972; JORDAN, SEPTEMBER 1970. 168. Memorandum From the President’s Assistant forInternational Economic Affairs (Flanigan) and the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs (Kissinger) to President Nixon. (link)

- FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1969–1976, VOLUME III, FOREIGN ECONOMIC POLICY; INTERNATIONAL MONETARY POLICY, 1969–1972. 131. Action Memorandum From the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs (Kissinger) to President Nixon. June 25, 1969. (link)

- Pompidou, G. and Nixon, R. February, 24, 1970. Memorandum of Conversation. (link)

- FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1969–1976, VOLUME XXXI, FOREIGN ECONOMIC POLICY, 1973–1976. 16. Conversation Among President Nixon, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve System Board of Governors (Burns), the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (Ash), the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers (Stein), Secretary of the Treasury Shultz, and the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs (Volcker). March 3, 1973. (link)

- FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1969–1976,VOLUME XXXI, FOREIGN ECONOMIC POLICY, 1973–1976. 61. Note From the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for International Finance and Development (Weintraub) to the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs (Volcker). March 6, 1974. (link)

- FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1969–1976, VOLUME XXXI, FOREIGN ECONOMIC POLICY, 1973–1976. 63. Minutes of Secretary of State Kissinger’s Principals and Regionals Staff Meeting. April 25, 1974. (link)

- Kissinger, H., Simon, W. March 14, 1973. Telephone call. (link)

Stay up to date, subscribe to Voima Insight—click here

The views expressed on Voima Insight are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official views or position of Voima Gold.

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com