Death, Taxes, & COVID-19: Things That Cannot Be Avoided

Tyler Durden

Fri, 09/18/2020 – 05:00

Submitted by Louis-Vincent Gave of GaveKal

In March, when Covid-19 began to rear its ugly head across the western world, national policy responses differed widely.

-

Denmark was the first European country to go on full lockdown, before the virus even really emerged in the country. As soon as news broke that Italian hospitals were being overwhelmed, Denmark shut its borders (in defiance of European Union laws), and shortly after, on March 11th, confined its population at home. Within two months, however, by May 11th, the Danish authorities gave shops, restaurants, bars, sports clubs etc. the green light to reopen.

-

France imposed possibly the most stringent lockdown in the western world. For two months, French citizens were only allowed to leave their homes for essential shopping—and only within a limited radius. Anyone stopped on the street had to produce a pass showing the time of departure from home, with no one allowed outside for more than an hour.

-

Sweden, in contrast, argued that lockdowns were a medieval response to the health problem. Instead of cowering behind closed doors, communities should look to build “herd immunity”. An economic shutdown would trigger other problems (suicide, alcoholism, drug abuse etc.) while locking people inside their homes could also trigger longer term difficulties (child abuse, domestic violence etc.).

-

Switzerland, like Sweden, never embraced the dramatic lockdowns imposed by other European countries, preferring to trust individual citizens to do the “right thing”. Heavy social pressures and public campaigns meant that most elderly stayed at home, even though it was not mandatory.

-

In the US, the federal structure of government meant that the responses varied greatly between regions, from lockdowns in New York, to full freedom in Arkansas.

These different policy choices carried different economic costs. In the second quarter of 2020, Sweden (usually one of the more volatile OECD economies given its integration into the global industrial supply chain and its limited domestic consumer base) outperformed all other OECD countries. Unsurprisingly, France delivered the worst economic performance, its GDP falling by almost a fifth.

But the declared priority in France, as in other countries that embraced full lockdowns, was to save lives; the government always acknowledged that such altruistic behavior would have economic costs. In short, President Emmanuel Macron, like many other policymakers around the world, accepted the certainty of massive economic loss for the chance of saving an indeterminate, but potentially large, number of lives.

At the risk of sounding horribly cynical, it is time to ask whether the tradeoff was worth it. With six months of data behind us, we can now count the economic costs of the lockdown (see the chart above), and we can also attempt to estimate the number of lives saved.

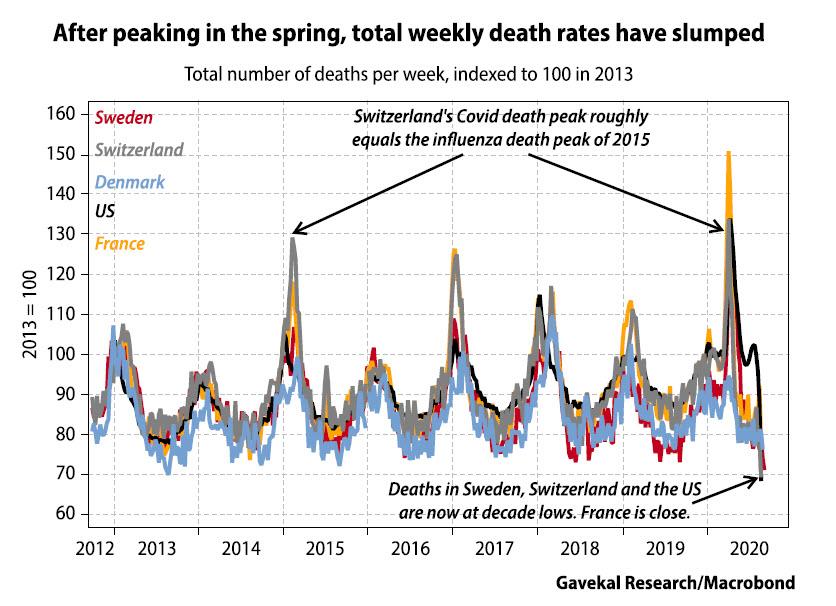

Comparing Covid-related death rates between countries is challenging, not least because different countries have adopted different standards for reporting Covid-related deaths—did the patient die of Covid, or with Covid? As a result, the least controversial way to review the impact of Covid on a country’s population is to look at the country’s total weekly deaths, and see how the numbers compare both to past years, and to the total numbers of deaths in other countries. Given the absence of wars and natural disasters, the assumption is that any “excess deaths” this year are mostly linked to Covid.

This approach is reasonable, because death, like taxes and policymakers’ responses to Covid, is one of those things that simply can’t be avoided—and governments are actually fairly competent at tracking the numbers of deaths that occur within their borders. In short, total death numbers are hard to fudge. Of course, the populations of Denmark, France, Sweden Switzerland and the US are vastly different. So to put every country on an equal footing, the data in the chart overleaf shows weekly numbers of deaths for each of these five countries indexed to 100 in 2013.

The chart is interesting for a number of reasons.

-

In general, more people tend to die in winter. Notably, however, these winter peaks tend to be less pronounced in Sweden and Denmark than in other countries. My best guess is that this shows how effectively the Scandinavians have adapted to their long and inclement winters.

-

When lots of people die in the winter, fewer die in the summer: the taller the winter’s death peak, the shallower the following summer’s trough tends to be. When the Grim Reaper has your number, your number is going to get called. And if by chance your number doesn’t get called in the winter, the chances are greater it will get called in the summer. Here, the 2020 divergence between Sweden and Denmark is interesting: Sweden had an abnormally high death rate over the winter, while Denmark had a “normal” death rate. Fast forward to this summer, and Sweden registered a record low death rate, while Denmark registered a normal death rate. This would seem to indicate that a significant number of the people who died of Covid last winter may well have died of other causes come the summer.

-

The number of total weekly deaths is now hitting decade lows in Sweden, Switzerland and the US. France is not at a new low, but is close to one (France suffered a couple of significant heat waves over the summer, and unfortunately heat waves tend to take their toll of frailer old folk). So, for all the continued panic about the spread of Covid and the rising number of cases, it seems the pandemic is no longer killing people as it did back in the winter. This fall in the number of deaths may indicate that the virus is becoming less deadly (which is common with respiratory viruses), or that health systems have found ways to treat the disease, such as steroid injections. But whatever the reason, it seems that on the scale of the broad population, Covid is no longer the mass murderer it was. So, do we really need to maintain economically-crippling and socially-debilitating anti-Covid measures?

-

Covid has undeniably caused excess deaths. But the March-April peak was of the same order of magnitude as recent “bad winters”. In Switzerland, which adopted a light touch approach to lockdowns, total weekly deaths at the peak of the crisis were similar to numbers at the worst of the 2015 winter. For France, Sweden and the US, the peaks were more pronounced, although not statistically dramatic (as Didier Darcet highlighted in April, see Modeling Projections For The Covid-19 Epidemic). In other words, it seems likely that in the age before social media, 2020 would have been considered a “harsh winter,” much like 1968-69 with the Hong Kong flu, or 2009 with the H1N1 pandemic. Most of us would have simply gone on with our lives.

-

It seems that France has managed not only to deliver the worst economic results, but the worst death toll. This may be a harsh assessment; the differences in the Danish, Swedish, Swiss, US and French death peaks are not that significant statistically. But despite following different policies, four out of these five countries delivered roughly the same outcomes. The exception was Denmark, which shut down much earlier than anybody else. This would seem to indicate that shutting the economy down only makes sense if it is done early. Otherwise, there is little point in closing the stable door when the horse has already bolted.

Aside from imposing a preventative early shutdown, the various differences in policy responses seem to have had little impact, neither reducing nor multiplying fatalities. This seems partially to vindicate the Swedish position that taking away civil liberties and shooting your economy in both feet made little sense, whether on human, economic, political or social grounds. The only exception appears to be if you do all these things very early on in the evolution of the disease. As the example of France (or the US, or the UK) shows, lockdowns do not appear to work if done too late.

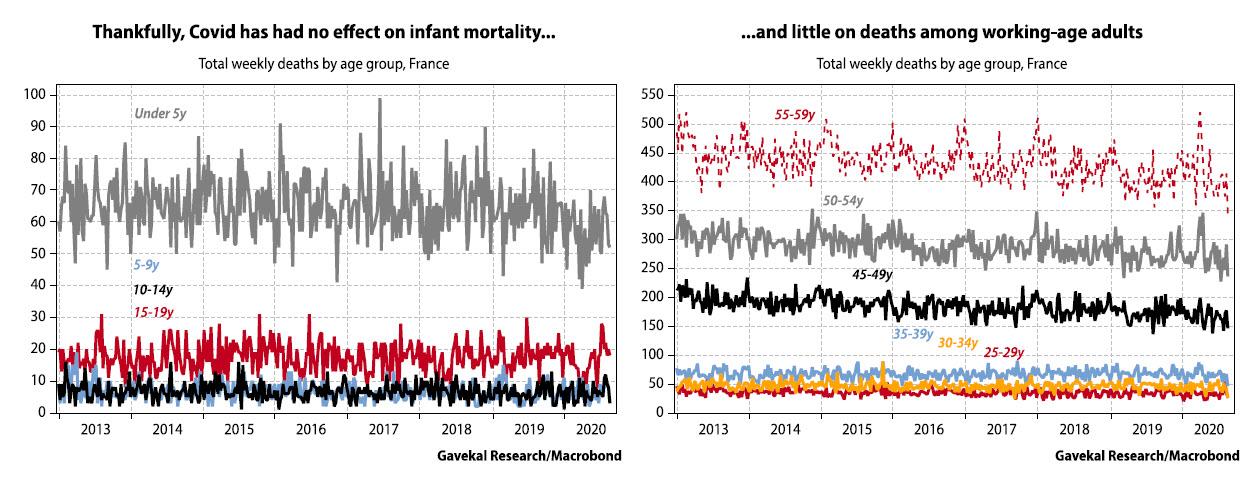

Another important point to highlight is that the disease has been (but no longer appears to be) a potent killer of old folk, but has broadly left children and working-age adults unaffected. The charts below show the data for France, but the data for other major western countries look broadly the same.

1). Thankfully, there is genuinely no sign that the Covid outbreak has had any impact on weekly deaths among French children.

2). There also seems to be no surge in deaths among France’s working-age population (most people in France, at least those that do not work at Gavekal, tend to retire at around 60).

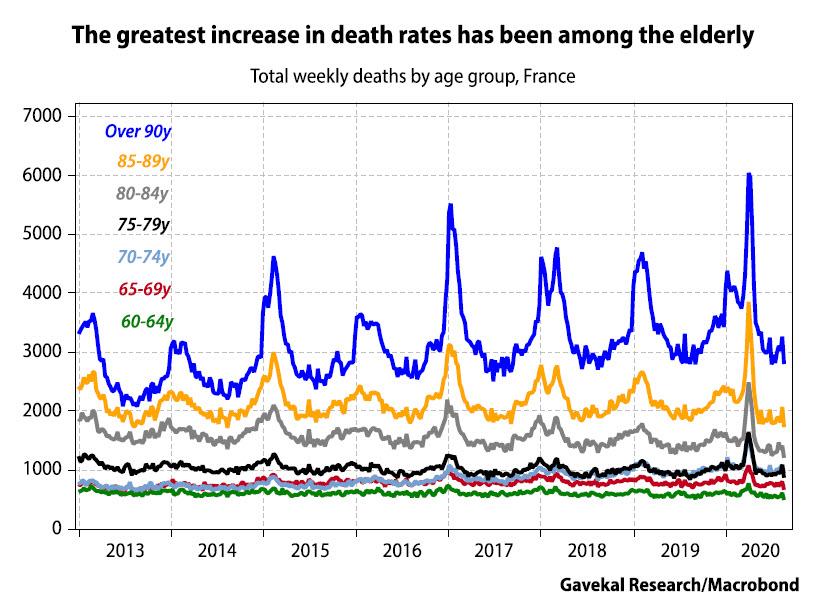

3) This means that the great surge in deaths occurred among retired folks. As the chart above makes clear, the statistically meaningful peaks in death rates occur in the 70-90-year-old age brackets, with the largest increase in deaths occurring among those aged over 90 (but that appears to be a feature of every winter).

So, given that death rates are now at long-term lows, and that the disease only seems disproportionately to kill folks coming to the natural end of their lives, why are policymakers still bickering about the reopening of schools (the UK), whether restaurants should be allowed to welcome patrons (New York), whether kids should be forbidden to go trick-or-treating this Halloween (Los Angeles), whether organized sports should even take place, and over the resumption of a dozen other everyday activities?

1) The first possible explanation is that policymakers are consciously making the choice to protect the old, even at the economic expense of the young. And they are doing this out of political calculation, because old people are more likely to vote than the young. However, this explanation runs counter to Hanlon’s razor, which states: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

2) The second possible explanation is that policymakers, having stumbled into this crisis, have now seized on the Rahm Emmanuel dictum “never let a good crisis go to waste.” For the last decade, lackluster growth across the western world has led to events as unfortunate (for policymakers) as the Brexit vote, Donald Trump’s election, the rise of the French yellow jacket movement, and the rise of the AfD in Germany and of Matteo Salvini in Italy. In other words, the sort of “pre-revolutionary” grumblings Gavekal warned of almost a decade ago (see Are We Entering Revolutionary Times?) are becoming ever-louder.

Disconcerted by this increasing roar, a number of policymakers have concluded that western economies are suffering from a lack of government intervention, combined with a shortage of fiscal spending, and insufficient money-printing. But cometh the crisis, cometh the moment to embark on the sort of Keynesian orgy Anatole has lately been applauding (see Why I Was Wrong To Turn Bearish and Why I Was Right To Turn Bullish). If to a hammer every problem looks like a nail, then to a large section of western policymakers, the answer to every problem increasingly seems to be more money-printing and more money-spending.

Of course, the real problem may not be Covid, but something else entirely. But then policymakers will use the pandemic as the pretext to embark on policies to fix the “something else”. This means they need to keep Covid humming in the background. How else could they justify the gradual introduction of some form of universal basic income funded by modern monetary theory or MMT (the magic money tree)? Combine this with a healthy dose of Parkinson’s Law at work, and governments have little incentive to walk back on any of their panic-mongering. Now that government commissions have been formed and funded to deal with the pandemic, are these commissions going to be in any rush to declare the pandemic over? Or are they more likely to insist that Covid remains a major threat, and that they need more funding to counter it?

3). Finally, the third and most likely explanation is that western governments were panicked into taking dramatic decisions. This panic was likely driven partly by the increased weight of social media in decision-making. Not that the absence of social media in the early years of the 21st century helped the US government take the right decisions in the aftermath of 9/11; the invasion of Iraq was one of the greatest policy failures in a generation. Now it is likely the Covid lockdowns will rank alongside Iraq in the policy failure “hall of shame”. We know from Adam Smith’s remark that “there is a great deal of ruin in a nation.” But at what point do repeated policy failures start to take their toll?

Staying with the Iraq analogy, one sure giveaway that policymakers realize lockdowns were a mistake is their insistence that they will not go down the full lockdown path again. And they say this even as they argue that the first lockdowns were essential to save countless lives. To me, this sounds a lot like Tony Blair’s insistence that the Iraq war was necessary, even as he claimed that if he had to make the same decision over, he would not send troops to Iraq again.

Another way in which the Iraq parallel may be appropriate is that policymakers do not know how to get out of the mess they’ve created. By invading Iraq, the US and the UK got involved in a war they soon found they could never fully “win”. And it was a war that drained large amounts of blood and treasure, at least until the US government decided to turn its back, and move on to the next thing. Today, policymakers face a similar problem: how can they declare victory over Covid and move on? Having stirred up fear and paranoia to new heights (dwarfing fears that Saddam Hussein could unleash chemical weapons against Europe), how do they now walk the fear back?

All this brings me to three possible conclusions:

-

For whatever reason, the virus, which now no longer seems to be killing people in anything like the numbers of last spring, flares up again, sending disproportionate numbers to (somewhat) early graves (let’s not forget that so far Covid has only been disproportionately deadly for older folk). However, given the recent data, there are no obvious reasons to think that this is a big risk.

-

Policymakers accept that they made a mistake and start to roll back their restrictions on civil liberties, schools, sports, businesses and so on. If so, voters could either (i) accept that the politicians meant well and let them off the hook, or (ii) decide to punish the incumbent politicians at the polls, with the democratic system continuing to gently tick over, ensuring that the incompetents are regularly thrown out of office (to be replaced by a different bunch of incompetents).

-

Instead of accepting that their restrictions are no longer relevant to the situation on the ground, Western politicians refuse to accept that they may have panicked at precisely the wrong time. But as the costs of doing business continue to rise and profits disappear, as parents stay stuck at home attempting to school their children, as families and friends find it impossible to gather, resentment against laws and regulations that no longer make sense starts to grow. This fosters disrespect for the government, disrespect for the regulators, and disrespect for the rule of law. Among a growing segment of the population, the maintenance of nonsensical Covid rules feeds the pre-revolutionary discontent that was already mounting in the years preceding Covid. It further fuels the anger in the countryside and second tier cities which already feel culturally, politically, and socially distant from the major cities were power resides and decisions are made.

* * *

My fear is that most Western countries, including my own—France—are now heading firmly down this third avenue: continued lockdowns, at the risk of engendering ever more contempt for government institutions. To put it simply: for politicians to pursue policies that ever-growing proportions of their populations are bound to reject is bad politics. We saw that much in last weekend’s yellow jacket demonstrations in Paris.

Still, against this bleak assessment, the one saving grace has to be that in most Western countries, today’s “swing voter” happens to live in the very countryside and second tier manufacturing cities that seem most inclined to reject the Covid-related laws handed down from on high. The hope has to be that democracy will continue to work, and that the policymakers who, like bad money managers, refuse to cut their losses and instead continue to “double when in trouble” will eventually find themselves fired at the ballot box.

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com