“Ridiculous”: $1 Trillion In Orders For $7 Billion Chinese Bond

In recent years, hardened bond market cynics snickered when insolvent European nations such as Italy or Greece saw 4, 5, or more times demand for their bond offerings than was for sale, whispering to themselves that such oversubscriptions for potentially worthless debt assure a very unhappy ending. Yet not even the biggest cynics were prepared for what just happened in China.

When Shanghai Pudong Development Bank sold $7 billion in convertible bonds last month, investors placed more than $1 trillion worth of orders, making this a 140 times oversubscribed offering, enough to shock even the most seasoned China investor, the FT reports.

That $1 trillion in bids was almost as large as the entire stock-market capitalisation of Apple or Microsoft — the two biggest companies in the world. “It was a ridiculous amount,” said Gerry Alfonso, head of research at Shenwan Hongyuan Securities in Shanghai. It is also a testament to how desperate the world has become in chasing yields and return, as well as just how much excess liquidity there is in the market at the moment

While new issue oversubscriptions have become the norm in recent years, this absurd case had several Chinese market unique characteristics, reflecting a surge in issuance of such equity-linked instruments in China — a rise helped by what the FT called “an unusual embrace of the product by policymakers better known for cracking down on financial innovations to ensure stability.”

So far this year, Chinese companies have issued a record $40bn in convertible bonds, up more than 80 per cent from the full-year total in 2018, according to Dealogic.

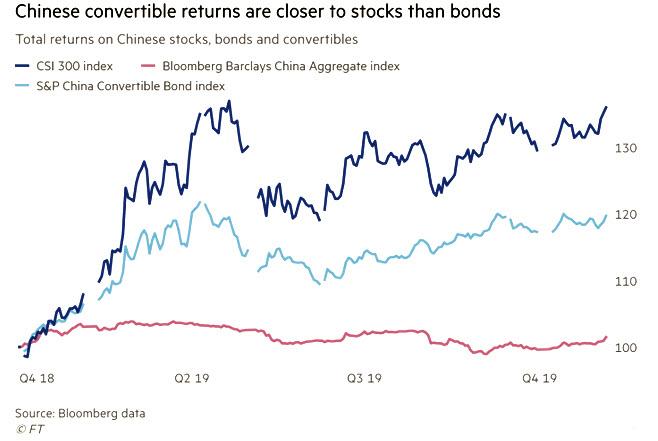

It now appears that converts have become the latest Chinese bubble due to their hybrid characteristics: while they carry a (lower) coupon payment they also offer investors the right to switch them for equity if a company’s shares rise to a certain price. For companies, convertibles offer a way to raise money more cheaply than by issuing regular debt and do not immediately dilute shareholders’ equity.

Ronald Wan, chief executive at Partners Capital in Hong Kong, said Chinese convertibles had become more attractive to investors thanks to this year’s stock rally, while the government was promoting the instruments as a way to rein in financing done off-balance sheet, or through a fragile shadow banking sector. Naturally, Wan cautioned that convertibles’ performance “depends on the quality of the issuer”, with investors typically prefering large banks and big blue-chip companies over small and mid-sized issuers, especially in a time when China’s smaller banks are either hit by bank runs or outright getting bailed out.

Shenwan’s Alfonso meanwhile warned that while large issuers such as Shanghai Pudong have seen ample liquidity in their convertibles after listing, investors in smaller issuers faced the prospect of taking heavy losses in the event of a sell-off.

“The liquidity is bad but there is liquidity,” he said. “The thing is, the price you’re going to get there is pretty horrendous.”

That, however, is not preventing every investor scrambling to be allocated a piece of the original bond in hopes of an early pop which can then be sold.

Some history: China’s first domestic convertible bond was issued in November 1992, two years after the Shanghai Stock Exchange opened. The bond, which never converted to stock, was the only onshore convertible issued for more than half a decade. Today’s market is different, as Chinese convertibles carry special features that set them apart from those in the US or Europe. For one, conversion levels can be reset after a bond is issued, significantly increasing the chances it will switch into stock.

But the biggest reason why there is unprecedented investor demand for convertibles right now is that – as of this moment – they tend to be looked on favorably by regulators because they are treated as debt until conversion, meaning investors have a better chance than equity shareholders of getting some form of repayment if the company goes bust. Bitcoin enthusiasts are well aware how violently prices can move depending on what Chinese regulators say.

Furthermore, Chinese companies are normally required to wait at least 18 months between offerings of shares, which makes convertibles a useful way to gain access to new funds quickly. “The process of [convertibles] approval still takes time — half a year or so — but it’s faster than an IPO or secondary offering,” said Yulia Wan, a senior analyst at Moody’s in Shanghai.

Ultimately, Chinese investors – well known for their propensity to jump from one bubble to another without giving it a second thought – are now rushing into converts due to hopes for quick capital appreciation. Wan said that because convertibles usually have a maturity of five to six years, a company’s shares have plenty of time to rise high enough for conversion.

The convertibles’ equity-like features mean they offer higher returns to investors than regular debt. But that alone does not explain the huge over-subscriptions common to the local market.

Alfonso of Shenwan Hongyuan said some of the rush is down to scarcity. Because existing shareholders are entitled to a large chunk of any convertible bond that is issued, the number of lots a company can offer more broadly is limited.

As such, those who want to get even a modest allocation have no choice but to submit massive bids in hopes of getting on the underwriter’s good side. Ultimately, investors know that they will get only a fraction of what they request. And because no money is required up front to make an offer, there is no reason not to bid as much as possible to maximise the odds of a successful purchase. “You put up as much as you can and hope for the best,” Alfonso said.

After all, what is the downside: it’s not like the Chinese are known to ever break a promise…

Commenting on the issue, Shard Capital’s Bill Blain writes that the Chinese converts remind him “of the glory days of the Japanese Equity Warrants market back in the 1980s. Ah, these were the days. How we played in stuff in we barely understood. Japanese companies we’d never ever heard of being the hot deal of the day, rumors of backhanders to ensure allocations and all kinds of shady goings on. These were the days….”

Much the same thing seems to be going on in Chinese convertibles – investors know they are hot so they put in vastly inflated orders in the hope they get some bonds. The future is a mobius strip loop of endless repeat moments.

Here’s the punchline: Shanghai Pudong’s insane 140x oversubscription is not even the biggest on record. As the FT notes, before regulators banned buyers from bidding through multiple accounts in March, it was not unusual for convertibles to be even more heavily over-subscribed. As such, the largest issuance on record of nearly $6bn, from China Citic Bank, was about 5,500 times oversubscribed, according to local media. That means that there were $33 trillion in orders for the bond offering, roughly three times the size of China’s entire economy.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 11/12/2019 – 20:45

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com