QE Or Not QE? Here Is The Market’s Answer In One Simple Chart

After a month of constant verbal gymnastics by the Fed – and its army of sycophants who can’t think creatively or originally and merely parrot their echo chamber in hopes of a blue checkmark and likes/retweets – that the recent launch of $60 billion in T-Bill purchases is anything but QE (whatever you do, don’t call it “QE 4”, just call it “NOT QE” please), two weeks ago one bank finally had the guts to say what was so obvious to anyone who isn’t challenged by simple logic: the Fed’s “NOT QE” is really “QE.”

As we reported on November 15, in a note warning that the Fed’s latest purchase program – whether one calls it QE, QE4, QE ∞ or NOT QE – will have big, potentially catastrophic costs, Bank of America’s Ralph Axel wrote that in the aftermath of the Fed’s new program of T-bill purchases to increase the amount of reserves in the banking system, the Fed made an effort to repeatedly inform markets that this is not a new round of quantitative easing, and yet as the BofA strategist notes, “in important ways it is similar.”

But was it QE? Well, in his October FOMC press conference, Fed Chair Powell said “our T-bill purchases should not be confused with the large-scale asset purchase program that we deployed after the financial crisis. In contrast, purchasing Tbills should not materially affect demand and supply for longer-term securities or financial conditions more broadly.” Chair Powell also gave a succinct definition of QE as having two basic elements: (1) supporting longer-term security prices, and (2) easing financial conditions.

Here’s the problem: as we have said since the beginning, and as Bank of America wrote, “the Fed’s T-bill purchase program delivers on both fronts and is therefore similar to QE,” with one exception – the element of forward guidance.

The upshot to this attempt to mislead the market what it is doing according to Bank of America, is that:

- the Fed is continuing to “ease” even though rate cuts are now on hold, which is supportive of growth, higher interest rates and higher equities, and

- the Fed is loosening financial conditions by increasing the availability of, and lowering the cost of, leverage, which broadly supports asset prices potentially at the cost of increasing systemic financial risk.

And while we have repeatedly argued why we think that, stripped of all its semantic veneer, the Fed’s latest asset purchase program is, in fact, QE, BofA effectively confirmed why we are right.

Which brings up a tangential, if just as important question: Why is the Fed so concerned about not signaling QE, and why are so many Fed fanboys desperate to parrot whatever Powell is saying day after day? Simply said, there are several reasons why the Fed is making a great effort to let the world know that its security purchases are not QE and are not reflective of any change in monetary policy stance.

The first is the obvious issue of signaling concern around the economic outlook which would run counter to its cautiously optimistic and often upbeat assessment. After all, why do QE if the economy has “never been stronger”, and the Fed was hiking rates as recently as a December. Included here are the concerns about running out of ammunition at the zero lower bound of rate policy. With negative rates increasingly off the table – until push comes to shove of course and the Fed is forced to join the ECB, BOJ and SNB in going subzero – QE is meant to be reserved as dry powder for a rainy day when conventional tools are exhausted (even if QE is in fact taking place this very instant).

A less obvious concern for the Fed is connecting monetary policy to bank demand for Fed liabilities, which as BofA admits, “is not something that fits neatly within its dual mandate”: last January, the Fed made a “momentous decision” to run an “abundant reserve regime” also known as a floor system, where the central bank decided not to return to its pre-crisis days of zero excess reserves. As such, the central bank now views the proper level of excess reserves (a Fed balance sheet liability) not in terms of its dual mandate for inflation and employment, but in terms of how banks prefer to meet regulatory liquidity requirements and how this preference impacts repo and other markets.

In short, the Fed’s dual mandate has been replaced by a single mandate of promoting financial stability (or as some may say, boosting JPMorgan’s stock price) similar to that of the ECB.

Here BofA ominously added that “by deciding to dynamically assess bank demand for reserves and reduce the risk of air pockets in repo markets, we believe the Fed has entered unchartered territory of monetary policy that may stretch beyond its dual mandate.” And the punchline: “By running balance-sheet policy to ensure overnight funding markets remain flush, the Fed is arguably circumventing the most important brake on excess leverage: the price.“

So if NOT QE is in fact, QE, and if the Fed is once again in the price manipulation business, what then?

According to BofA’s Axel, the most worrying part of the Fed’s current asset purchase program is the realization that an ongoing bank footprint in repo markets is required to maintain control of policy rates in the new floor system, or as we put it less politely, banks are now able to hijack the financial system by indicating that they have an overnight funding problem (as JPMorgan very clearly did) and force the Fed to do their (really JPMorgan’s) bidding.

While it is likely that beyond year-end, the additional tens of billions in reserves will have the required soothing effect, what is less clear is that the Fed can make sure the bank repo lending footprint is resilient to dips in the bank credit cycle.

And this is where BofA’s warning hits a crescendo, because while repo is fully collateralized and therefore contains negligible counterparty credit risk, “there may be a situation in which banks want to deleverage quickly, for example during a money run or a liquidation in some market caused by a sudden reassessment of value as in 2008.”

Got that? Going forward please refer to any market crash as a “sudden reassessment of value”, something which has become impossible in a world where “value” is whatever the Fed says it is… Well, the Fed or a bunch of self-serving venture capitalists, who pushed the “value” of WeWork to $47 billion just weeks before it was revealed that the company is effectively insolvent the punch bowl of endless free money is taken away.

To Bank of America, this new monetary policy regime actually increases systemic financial risk by making repo markets more vulnerable to bank cycles. This, as the bank ominously warns, “increases interconnectedness, which is something regulators widely recognize as making asset bubbles and entity failures more dangerous.“

Think of this as Europe’s infamous “doom loop”, only in the US and instead of linking bank equity values with the price of sovereign debt, it uses repo as a risk intermediary – one which is both used to grease the financial system, and which henceforth will also be an indicator of systemic bank stress.

In short, not only is the Fed pursuing QE without calling it QE, but by doing so it is implicitly raising the odds – more so than if it simply did another QE and rebuilt reserves to abour $4.5 trillion or more by purchasing coupon bonds – of another market crash.

It was, however, BofA’s conclusion that we found most alarming: as Axel writes, in his parting words:

“some have argued, including former NY Fed President William Dudley, that the last financial crisis was in part fueled by the Fed’s reluctance to tighten financial conditions as housing markets showed early signs of froth. It seems the Fed’s abundant-reserve regime may carry a new set of risks by supporting increased interconnectedness and overly easy policy (expanding balance sheet during an economic expansion) to maintain funding conditions that may short-circuit the market’s ability to accurately price the supply and demand for leverage as asset prices rise.“

In retrospect, we understand why the Fed is terrified of calling the latest QE by its true name: one mistake, and not only will it be the last QE the Fed will ever do, but it could also finally finish what the 2008 financial crisis failed to achieve, only this time the Fed will be powerless to do anything but sit and watch.

All of this, and more, we discussed previously in “One Bank Finally Admits The Fed’s “NOT QE” Is Indeed QE… And Could Lead To Financial Collapse.”

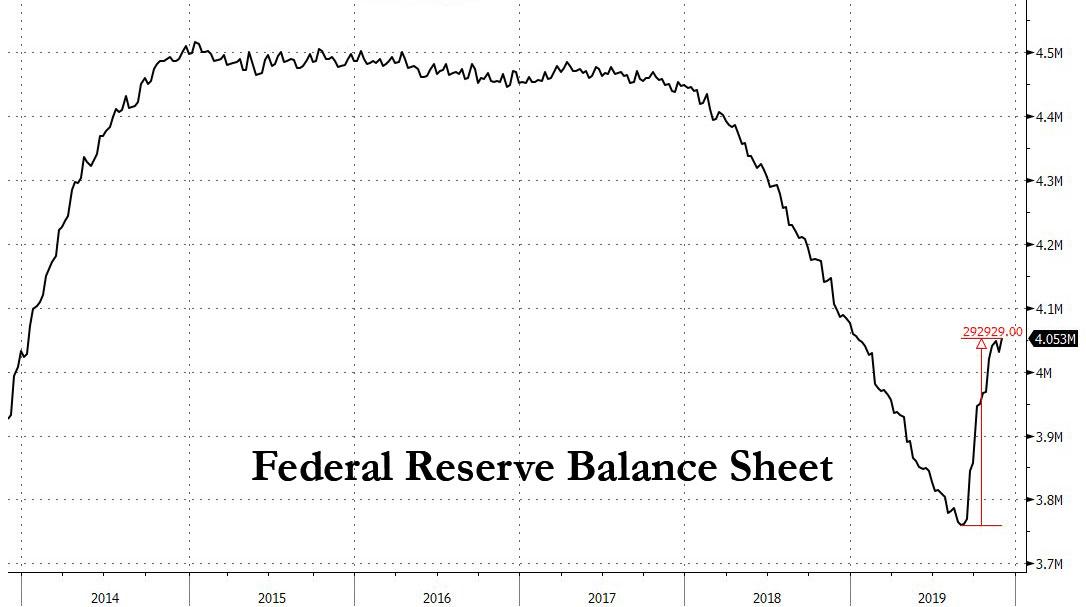

The reason we bring up this especially critical topic again today, is because we now have almost two full months of data since the start of NOT QE, which IS QE, and which conveniently gives us a snapshot of how the market – not we, not Bank of America, not pro or anti-Fed pundits – are responding to the expansion in the Fed’s balance sheet, which between repos, term repos, and permanent open market operations, has grown by $293 billion in just under the past three months.

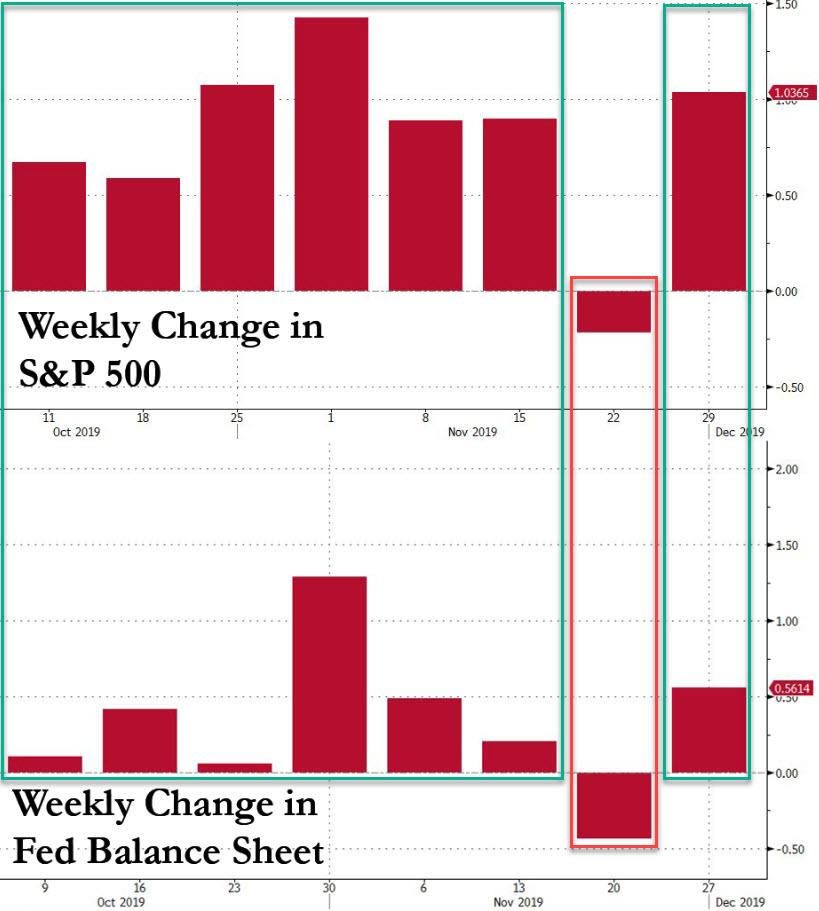

The simple answer is the following: whether one wants to call it QE or not QE, ever since the Fed announced on Oct 11 that it would start purchasing $60 billion in T-Bills each month until “at least into the second quarter of 2020” – being careful to note that “these actions are purely technical measures to support the effective implementation of the FOMC’s monetary policy, and do not represent a change in the stance of monetary policy“, i.e., this is not QE, the Fed’s balance sheet has grown for 7 out of 8 weeks.

The market’s response? Just like during the POMO days of QE1, QE2, Operation Twist, and QE3, stocks have risen on every single week when the Fed’s balance sheet increased, following the three weeks of declines that led to the October 11 announcement. What about the one week when the Fed’s balance sheet shrank? That was the only week in the past two months since the launch of “NOT QE” when the S&P dropped.

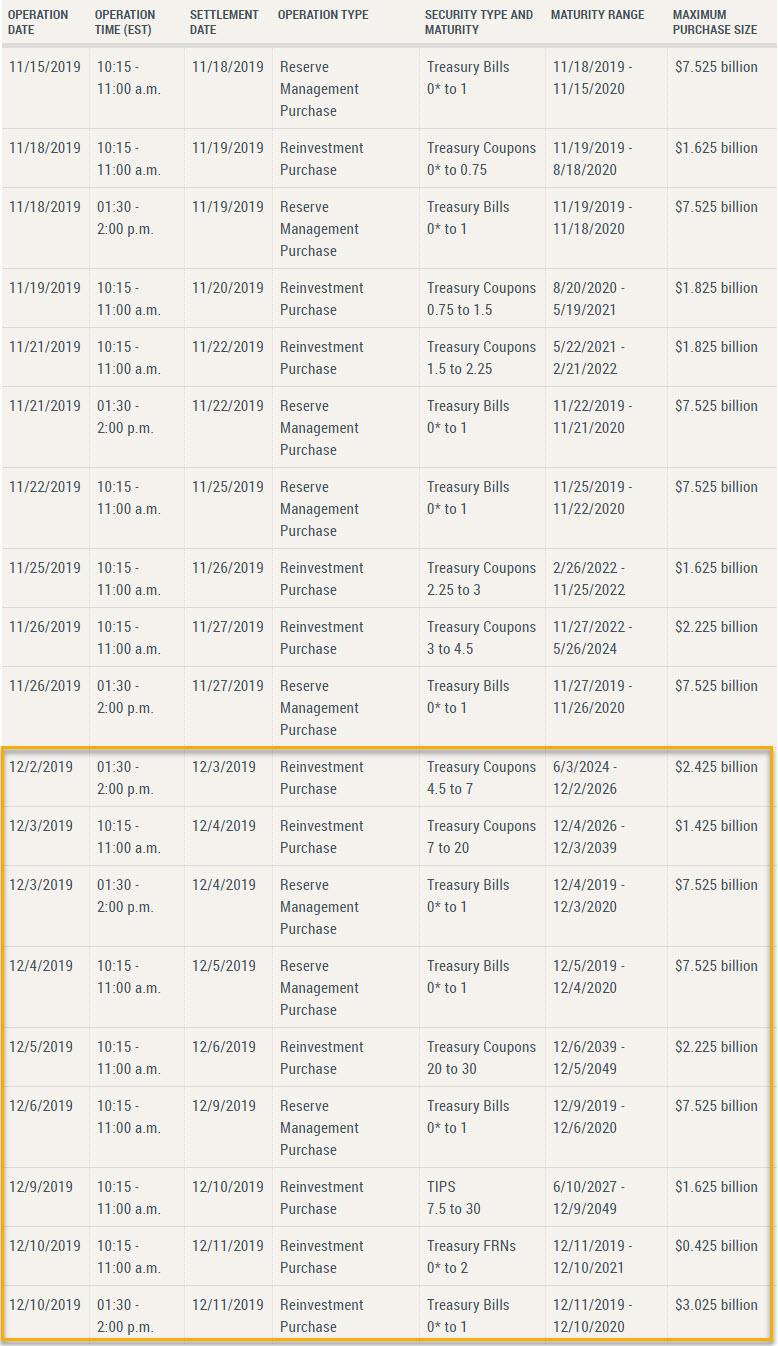

So while Fed watchers, pundits, strategists, rank amateurs and virtually anyone else can debate whether or not what the Fed is doing is or is not QE, the market has made up its mind: if the balance sheet is rising, so are stocks, and vice versa. And since only POMO matters – so to speak – as it did back in the days of QE1 through QE3, we will do what we did back then, and list a schedule of all the upcoming days in which the Fed conducts liquidity injections – regardless of how one wants to call them (the latest schedule can always be found on the following page).

One final point for all those who despite the above, will still claim that just because the Fed is not purchasing coupon Treasuries, and thus is not changing either the duration of securities in the open market or investor risk preference, it is not, not, not QE, here is a snippet of what JPMorgan’s Nikolaos Panagirtzoglou wrote in his latest Flows and Liquidity newsletter:

… we see the Fed likely to conduct some of its balance sheet expansion next year via Treasuries.

Translation: some time in 2020, the Fed will stop pretending it is “NOT” QE.

Case closed.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 11/30/2019 – 17:00

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com