China’s “Moment Of Reckoning” Arrives: $38BN State-Owned Giant Announces Largest Dollar Bond Default In Two Decades

Two weeks ago we previewed what we said would soon be a D-Day for China’s bond market, as a massive commodities trader and Global 500 state-owned enterprise was set for an “unprecedented” bond default.

As of last week, this historic default is now in the history books after Tewoo, the closely watched Chinese commodities trader, became the biggest dollar bond defaulter among the nation’s state-owned companies in two decades, in what Bloomberg called a “moment of reckoning” for Beijing as China struggles to contain credit risk in a weakening economy, as bond defaults hit an all time high and are set to keep rising in the coming years.

Last Wednesday, Tewoo Group announced results of its “unprecedented” debt restructuring, which saw a majority of its investors accepting heavy losses, and which according to rating agencies qualifies as an event of default. As a result of the default, until recently seen as virtually impossible for a state-owned company, investors’ perceptions are undergoing a dramatic U-turn about government-owned borrowers whose state-ownership had for years offered an ironclad sense of security.

No more: The fact that a state-owned enterprise such as Tewoo has now defaulted on repaying its dollar bonds in full, confirms that Beijing will no longer bail out troubled SOEs, let alone private firms, perhaps due to the strains imposed by the economy which while growing at just below 6%, is slowing the most in three decades. It also raises concerns over the Chinese province of Tianjin, where Tewoo is based, following a series of rating downgrades and financing difficulties suffered by some of the city’s state-run firms. The metropolis near Beijing also has the highest ratio of local government financing vehicle bonds to GDP in China.

As a reminder, Tewoo ranked 132 in 2018’s Fortune Global 500 list, higher than many other conglomerates including service carrier China Telecommunications Corp. and financial titan Citic Group Corp. It had an annual revenue of $66.6 billion, profits of about $122 million, assets worth $38.3 billion, and more than 17,000 employees as of 2017, according to Fortune’s website. Tewoo is owned by the Tianjin government and operates in a number of industries including infrastructure, logistics, mining, autos and ports, according to its website. It also has footprints in countries including the U.S., Germany, Japan and Singapore.

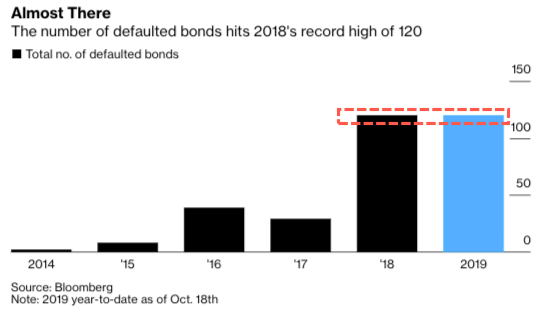

Putting last week’s “unprecedented” event in context, since the first SOE bond default emerged in China’s domestic market four years ago, 22 such firms have failed to make good on a combined 48.4 billion yuan ($6.9 billion) onshore bonds as of the end of October, according to Guosheng Securities. However, despite periodic scares such as late repayment, Chinese SOEs had yet to suffer any high-profile default in the dollar bond market since the collapse of Guangdong International Trust and Investment Corp. in 1998.

Tewoo is precisely that default.

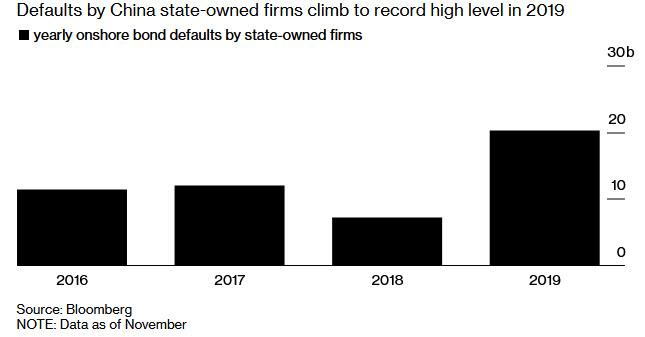

Furthermore, Tewoo’s exchange offer, which has bondholders accepting a major haircut on their bonds, is seen as a road-map for resolving similar debt crises in the future as the prospect of more failures by state-backed firms looms. 2019 has already seen over 20 billion in SOE bond defaults, nearly triple 2018’s total and the highest on record.

Specifically, the former Fortune Global 500 company from the northern port city of Tianjin said dollar bond investors representing 57% of the the total $1.25 billion have agreed to be paid just 37 to 67 cents on the dollar, depending on the maturity of the bonds. Additionally, bondholders representing 22.6% of these bonds voted to exchange their debt for new bonds with sharply lower coupons to be issued by Tewoo’s offshore debt manager, a state asset manager from Tianjin.

“This is one form of default based on our definition,” said Moody’s analyst Ivan Chung, pointing out that the debt restructuring has resulted in losses for investors.

The distressed exchange offer which concluded hastily last week represents a “first of its kind” debt restructuring plan for the relatively immature Chinese bond market and for a state-run enterprise in the dollar bond market. It was rushed ahead of $300 million dollar bond maturity on Dec. 16, one of the four notes covered by Tewoo’s debt restructuring plan.

To be sure, the market was not surprised: late last month, Tianjin State-owned Capital Investment and Management, Tewoo’s offshore debt manager, said on an investor call that Tewoo is very likely to default on this paper. That explains why Tewoo’s bond prices were largely unchanged after the exchange offer.

Meanwhile, investors who turned down the company’s forced exchanges face even steeper losses; their dollar bonds will be grouped into a comprehensive debt plan involving Tewoo’s onshore debt, according to Tianjin State-owned Capital.

Tewoo said settlement of the debt restructuring offers are expected to be on or about Dec. 17.

As Bloomberg summarizes, “Tewoo’s failure in the dollar bond market, the biggest for a Chinese SOE since the collapse of Guangdong International Trust and Investment Corp. in 1998, is a sign that the worst economic slowdown in three decades is limiting Beijing’s capacity to bail out its weaker state firms. As a result, the authorities appear increasingly willing to use a more market-oriented approach to clean up the mess.”

“Tewoo’s default is a landmark case, and demonstrates a growing tolerance for defaults by distressed SOEs,” Cindy Huang, an S&P Global Ratings credit analyst said in a note.

Needless to say, Tewoo’s crisis comes as a wake-up call for investors, many of whom had expected to never incur losses in China’s offshore (dollar) bond market where until now, moral hazard had been the only game in town. Alas, that game is now changing.

“This is a poor outcome for investors that bought the bonds at par. That said, there is now some track record as to the severity of loss for an SOE-related entity,” said Charles Macgregor, head of Asia at Lucror Analytics. “Hopefully, these types of restructures will bring more discipline to the market and result in investors properly pricing for the apparent risk,” he added hopefully, although with developed nation central banks engaging in precisely the kind of moral hazard boosting activity that China is now desperately seeking to distance itself from, we doubt that any investors will learn any lessons, and if anything, creditors will only demand even bigger bailouts in the future.

* * *

What is perhaps just as concerning is that as we noted last month, the Tewoo default is a harbinger of the crisis facing China’s insovent local governments themselves. Tianjin “is not an exception” and other local governments with deteriorating fiscal conditions might also see eroding support for their less competitive SOEs, S&P warned.

It all started with the bankruptcy of Bohai Steel Group in 2018 which triggered systemic risk in Tianjin’s financial market. The incident involved a large number of local companies and financial institutions, which recorded huge amounts of bad debt. Financial institutions became more conservative in their lending standards, and this resulted in liquidity issues for a number of Tianjin enterprises.

At the same time, Beijing’s deleveraging and capacity reduction reforms made it difficult for a traditionally highly-leveraged company like Tewoo to raise financing. The default in May 2018 by Hsin Chong Group Holdings Limited, a company controlled by Tewoo, showed further signs of financial problems at Tewoo Group.

While normally such a critical company as Tewoo would be quietly bailed out by either Beijing or the local province, investors told Bloomberg that the company’s excessive debt levels would limit Tianjin authorities’ ability to lend support to the city’s troubled firms. They were right, and in July, Tianjin Binhai New Area Construction & Investment Group postponed plans to sell a three-year dollar bond offering amid such concern.

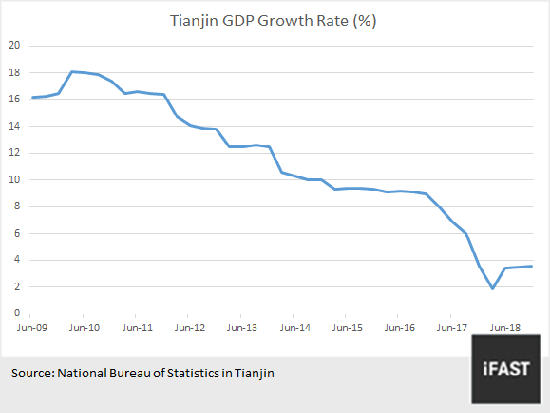

Tewoo’s debt issues that had surfaced from its current crisis may be only the tip of the iceberg. Tianjin’s economic growth has slowed down sharply since the beginning of 2016. GDP growth dropped to 1.9% in the first quarter of 2018. Even as it started to rebound thereafter, the outlook is still pessimistic, with GDP growth in 2018 less than 4%, which ranked last in the country according to iFast.

On the other hand, according to a 2016 report released by ratings agency Moody’s, state-owned enterprises in Tianjin recorded an aggregate liability-to-fiscal revenue ratio of more than 600%, which was the highest in the country.

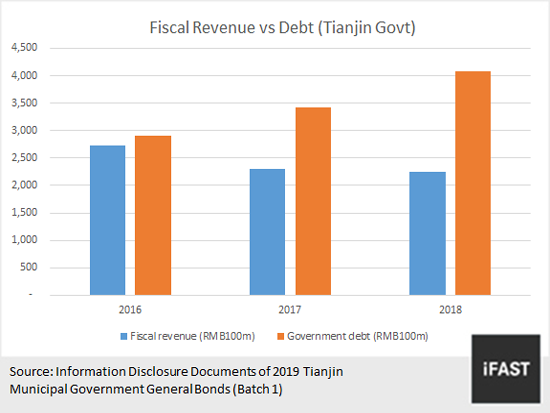

At the same time, as shown in Tianjin municipal government’s most recent three-year revenue and debt data, Tianjin government’s fiscal revenue has declined significantly since 2017. Fiscal revenue fell by close to RMB40 billion in 2017, while government borrowings rose rapidly. By the end of 2018, debt owed by the Tianjin government was almost double its fiscal revenue.

The bankruptcy of Bohai Steel, a Tianjin SOE, in 2018 may also be a sign that the Tianjin government has lost control over the local debt crisis. Other than Bohai Steel and Tewoo, there have been a number of state-owned companies in Tianjin that are fighting to stave off insolvencies, such as Tianjin Real Estate Group Co. Limited, which owes RMB200 billion in debt. From the above observations, we think that in the event of a default by Tewoo, the company is likely to go into bankruptcy reorganization in a similar way as Bohai Steel, which has brought in capital from the private sector for its corporate restructuring. But for bondholders, recovery of their investments may be difficult, and potential loss heavy.

With Tianjin failing – or simply unable to step up, in the aftermath of Tewoo’s debt restructuring which confirms that Beijing will no longer bail out even SOEs, investors’ skepticism about state support for such state-linked firms will collapse, and the default will have wide, and dire, implications on how investors assess and price their bonds in the future, said Judy Kwok-Cheung, director of fixed-income research at Bank of Singapore. It will certainly have a chilling effect on demand for Chinese bond issuers as investors will actually have to perform due diligence to find out just what they are buying.

“Investors would be going back to basics in assessing credit risk in that the company’s stand-alone ability to repay is the first line of defense when it comes to non-repayment risk,” said Kwok-Cheung.

In short, “investors” would be reacquainted with a thing called “fundamentals.” The horror, the horror.

* * *

It gets worse: should Tewoo’s default spread to provincial-backed debt, an already ugly situation could quickly turn catastrophic as Tianjin has the highest debt burden among mega-cities and provinces in China according to S&P. Earlier this year, Fitch cut ratings on several government-related entities from the city, which is reliant on heavy industry and commodities trading. As a result of having the highest debt, Tianjin also has to slowest growth – Tianjin’s local economy grew by just 3.6% last year, the slowest in China; at the end of last year, Tianjin’s government had 407.9 billion yuan worth of debt outstanding, or about 22% of the size of its economy, said the Chinese credit risk assessor.

And just in case the Tewoo default isn’t troubling enough, Moody’s said that it expected the number of Chinese defaults to jump further in 2020 as economic growth sputters and the government attempts to rein in support to indebted companies. Specifically, Moody’s expects 40-50 new defaults in 2020, up from 35 this year, according to Ivan Chung, which will make next year another all time high.

“The regulators’ intention is to reduce moral hazard” while at the same time ensuring any defaults “won’t undermine socioeconomic stability or trigger systemic risks,” Chung said on Wednesday, who added that whereas state support may be available for companies engaged in social welfare projects, for those that are more commercial in nature, “government support may not be so forthcoming,” he said.

So what happens next?

Now that a Tewoo event of default is in the history books, the next question is what will bondholders of China’s other SOE’s – those who bought bonds on the assumption that China will always bail them out – do next? A flurry of aggressively selling may be just the catalyst that cracks the market if it emerges in the extremely illiquid days just before Christmas.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 12/14/2019 – 20:00

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com