China Faces “Systemic Risk” From Debt Cross-Default “Chain Reaction”, Top Central Bank Advisor Warns

Just days after China’s “moment of reckoning” in the dollar bond market arrived, when China was rocked by not only the biggest dollar bond default in two decades but also the first default by a massive state-owned commodities trader and Global 500 company, when Tianjin’s Tewoo Group announced the results of its “unprecedented” debt restructuring which saw a majority of its bondholders accepting heavy losses, and which according to rating agencies qualified as an event of default, last week a top adviser to China’s central bank warned of a possible “chain reaction” of defaults among the country’s thousands of local government financing vehicles after one of these entities nearly missed a payment this month.

As the FT reported, Ma Jun, an external adviser to the People’s Bank of China, called on the government to introduce “intervention mechanisms” to contain the risk associated with LGFVs — special entities used in the country to fund billions of dollars of roads, bridges and other infrastructure.

“Among the tens of thousands of platform-style institutions nationwide, if only a few publicly breach their contracts it may lead to a chain reaction,” Ma said in an interview published on Wednesday in the state-controlled Securities Times newspaper, adding that “measures should be created as soon as possible to prevent and resolve local hidden debt risks to effectively prevent the systemic risks of platform default and closure.”

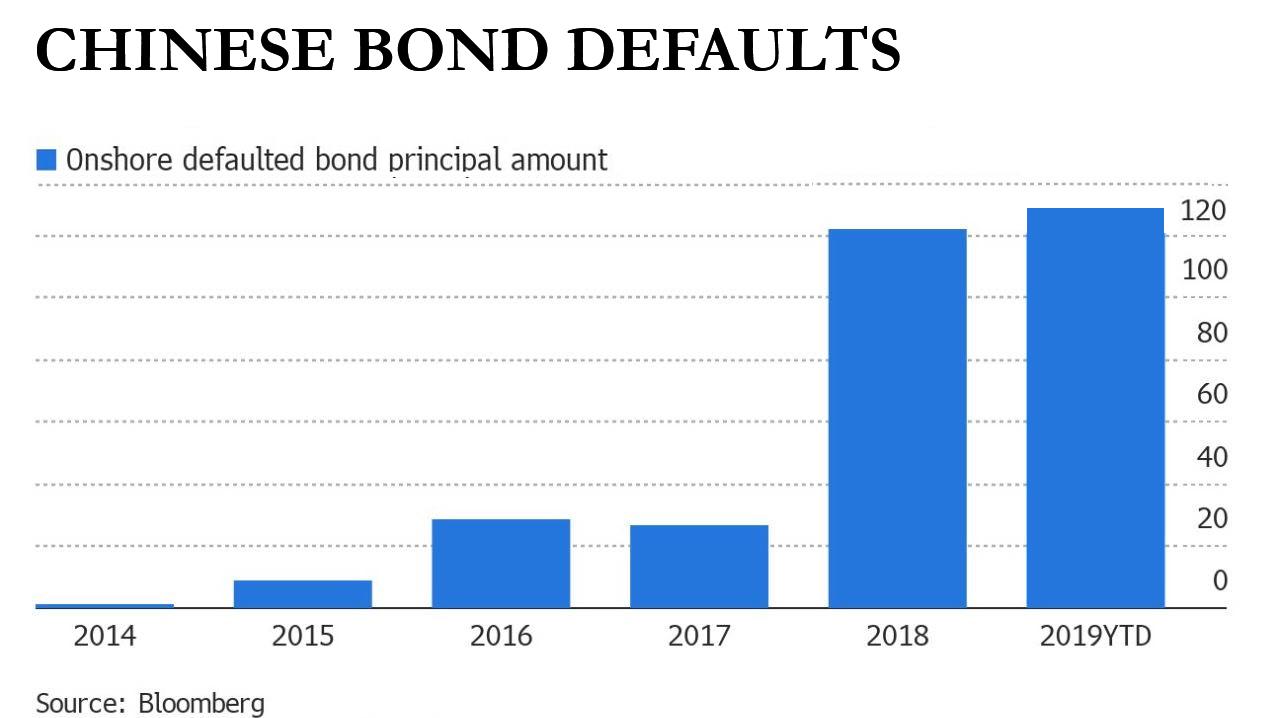

Ever since Beijing allowed local corporations to fail, China has seen a surge in corporate defaults in local currency and US dollar bonds as economic growth grinds to a 30-year low. As we reported recently, China is set to hit another dismal milestone in 2019 when a record amount of onshore bonds are set to default, confirming that something is indeed cracking in China’s financial system and testing the government’s ability to keep financial markets stable as the economy slows and companies struggle to cope with unprecedented levels of debt.

After a brief lull in the third quarter, a burst of at least 20 new defaults since the start of November have sent the year’s total to 131 billion yuan ($18.7 billion), eclipsing the 121.9 billion yuan annual record in 2018.

While this still represents a tiny fraction of China’s $4.4 trillion onshore corporate bond market, the bad news is that the rapidly rising number is approaching a tipping point that could unleash a default cascade, and in the process fueling concerns of potential contagion as investors struggle to gauge which companies have Beijing’s support. As Bloomberg notes, policy makers have been walking a tightrope as they try to roll back the implicit guarantees that have long distorted Chinese debt markets, without dragging down an economy already weakened by the trade war and tepid global growth.

Meanwhile, that “tipping point” could arrive much faster if a surge in government-linked defaults creates a crisis of confidence in China debt markets, which have long been protected by implicit state guarantees.

Besides the record number of default in the local bond market and the recent groundbreaking default of the dollar bonds issued by the state-owned Tewoo, concern has grown in recent months over the vast accumulation of debt in LGFVs, especially after the near default of one such financing platform, Hohhot Economic and Technological Development Zone Investment Development Group, in the Chinese autonomous region of Inner Mongolia earlier this month.

To avoid a cascading collapse in confidence among China’s creditors, Ma proposed one potential measure to allow for distressed LGFVs to be taken over by healthier one, very much similar to how a record number of China’s small and medium banks were “resolved” in 2019, despite at least two bank runs being triggered last month as previously reported.

The comments by Ma, a former Deutsche Bank economist, come as concerns grow in China’s central government about rising systemic risk. At a high-level planning session in Beijing earlier this month, at which many of the next year’s economic challenges are discussed among senior officials, the avoidance of systemic risk was listed as a priority.

“At the meeting, China’s top policymakers stressed stable macro policy with flexible fine-tuning, and pledged to prevent systematic financial risks,” Mizuho Securities economist Serena Zhou said in a report to investors this month, noting that “such a pledge came the same day as Hohhot Economic and Technological Development Zone Investment Development Group, a LGFV 100 per cent owned by the Hohhot local government, reportedly missed its bond payment.”

And while the Hohhot group’s repayment deadline was eventually extended after the group failed to repay a 1 billion yuan ($142 million) privately placed bond earlier this month, the situation grabbed the attention of both creditors in other similar LGFV situations as well as analysts.

As the FT notes, China’s LGFVs have been key drivers of economic growth in China since the mid-1990s, backing many of the local infrastructure projects that have boosted growth rates in recent years. But they are also closely connected to China’s shadow banking sector, making it difficult for central authorities to fully assess the risk connected to the groups.

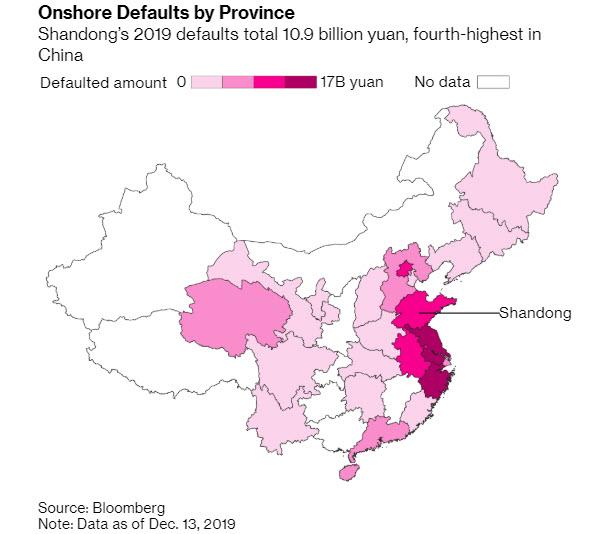

Meanwhile, adding to Beijing’s list of “default domino” default woes, in addition to rising fears about the stability of LGFVs, Bloomberg points out that the rising default tide is now impacting even one of China’s wealthiest provinces, namely Shandong, where six privately owned companies have defaulted on their debt or come close to doing so in the last three months. With 68.1 billion yuan ($9.7 billion) in outstanding debt among those six companies alone, “the distress in Shandong has rattled even seasoned investors.”

Of course, the problem isn’t the defaults themselves, as many other provinces have seen more and worse – just last month we showed how cash-strapped Tianjin could soon be ground zero for a Chinese default quake in 2020. The far greater risk as Bloomberg notes, is the practice common among Shandong companies of guaranteeing each others’ debts. As firms don’t have to make public such “off balance sheet” liabilities, investors are left in the dark who’s on the hook and for how much. And with China’s once-strong industrial economy flagging, the murky ties between the province’s private companies threaten to drag them all down together.

And with a sharp rise in defaults in both the local and dollar bond markets, and LGFVs teetering, it’s still unclear how the government will intervene in Shandong and elsewhere. Policy makers have been increasingly willing to let weak companies fail, but they’re also under pressure to keep the economy growing and the markets stable.

As of now, Shandong’s city and local governments have stepped in with piecemeal relief. It’s uncertain whether the provincial government will do the same. As a result, the province’s firms risk entering a vicious cycle that “spreads solvency risks to the entire region, swamping the good credits along with the bad,” according to an October report from S&P Global Ratings.

While the default rate for bonds issued by non-state companies across China jumped to a record 4.5% in the first 10 months of 2019, Fitch Ratings warned in a Dec. 3 report that the figure might understate the true level of defaults given that some borrowers settle with bondholders privately rather than through clearing houses. The rate for state-owned companies was just 0.2% thanks to financial support from the government and better access to funding from banks, Fitch said, but even that is set to surge in 2020 following the closely-followed Tewoo bankruptcy.

As Bloomberg notes, Shandong is one of China’s oldest economic centers, built first on trade, then agriculture, mining and oil drilling. Not long ago, the economy was still booming, credit was cheap and private firms were on a spending spree, restrained only by limited access to capital. In communist-run China, state-owned banks tend to favor state-owned companies for loans.

So city governments encouraged the private sector to support itself. Cross-guarantees were one solution. They also concentrated the financial risks, says S&P analyst Cindy Huang.

“Cross-guarantees tend to be clustered around certain cities and regions rather than across the province,” she said. “They’re often between private, unlisted companies from either the same city, same sector or where CEOs know one another.”

So to loosely paraphrase Ernest Hemingway, “How did you go bankrupt? Two ways: Gradually and then suddenly… and when you do, you take down all your friends down with you.”

That’s precisely what China has in store for bondholders of its massive $40 trillion financial sector in the coming years.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 12/21/2019 – 18:00

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com