“It Will Be Really, Really Bad”: China Faces Financial Armageddon With 85% Of Businesses Set To Run Out Of Cash In 3 Months

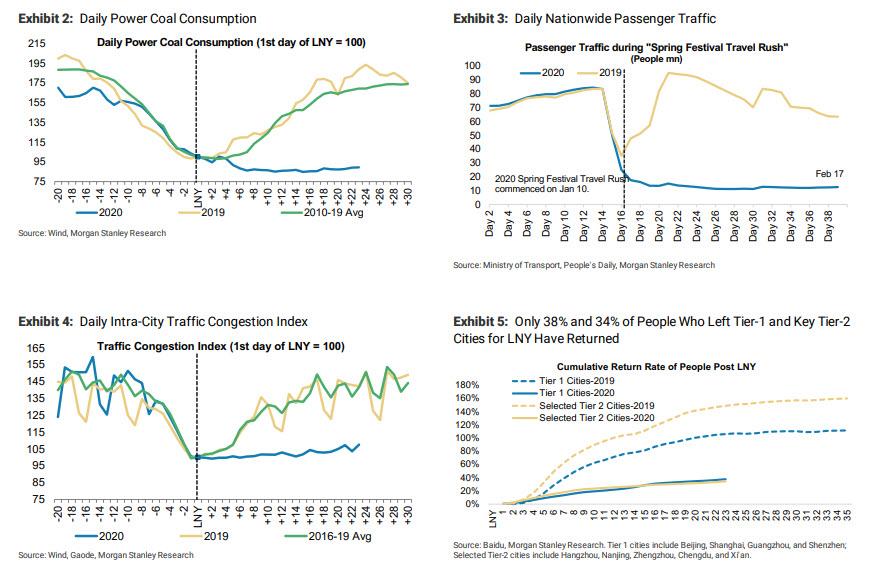

For the past two weeks, even as the market took delight in China’s doctored and fabricated numbers showing the coronavirus spread was “slowing”, we warned again and again that not only was this not the case (which recent data out of South Korea, Japan and now Italy has confirmed), but that for all its assertions to the contrary, China’s workers simply refused to go back to work (even with FoxConn offering its workers extra bonuses just to return to the factory) and as a result the domestic economy had ground to a halt as we described in:

- China Has Ground To A Halt: “On The Ground” Indicators Confirm Worst-Case Scenario

- China Is Disintegrating: Steel Demand, Property Sales, Traffic All Approaching Zero

- Terrifying Charts Show China’s Economy Remains Completely Paralyzed

Unfortunately, it’s not getting any better as the latest high frequency updates out of China demonstrate:

Also unfortunately, it is getting worse, because as we explained several weeks ago, China is now fighting against time to reboot its economy, and the longer the paralysis continues, the more dire the outcome for both China’s banks and local companies. And since it is no longer just “scaremongering” by “conspiracy blogs”, but rather conventional wisdom that China may implode, here is a summary of how the narrative that “it will all be over by mid-March” is dramatically changing.

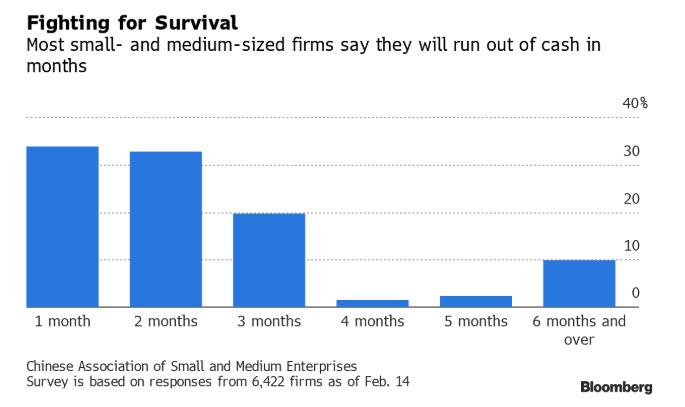

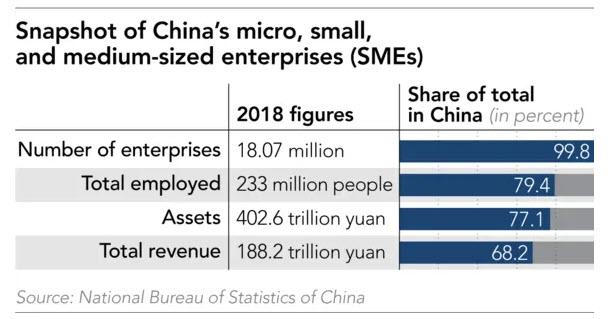

Let’s start with Chinese businesses: while China’s giant state-owned SOEs will likely have enough of a liquidity lifeblood to last them for 2-3 quarters, it is the country’s small businesses that are facing a head on collision with an iceberg, because according to the Nikkei, over 85% of small businesses – which employ 80% of China’s population – expect to run out of cash within three months, and a third expect the cash to be all gone within a month.

Should this happen, not only will China’s economy collapse, but China’s $40 trillion financial system will disintegrate, as it is suddenly flooded with trillions in bad loans.

Take the case of Danny Lau who last week reopened his aluminum facade panel factory in China’s southern city of Dongguan after an extended Lunar New Year break. To his shock, less than a third of its roughly 200 migrant workers showed up.

“They couldn’t make their way back,” the Hong Kong businessman said. Most of his workers hail from central-western China, including 11 from Hubei Province, the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak that has killed more than 2,000 people. Many said they had been banned from leaving their villages as authorities race to contain the epidemic.

Lau’s business had already been hurt by the 25% tariff on aluminum products the U.S. imposed in its tit-for-tat trade war with China. Now he worries the production constraints will give American customers another reason to cancel orders and switch to Southeast Asian suppliers. The virus is making a bad situation “worse,” he said.

Lau is not alone: this same double blow is hitting small and midsize enterprises across China, prompting a growing chorus of calls for the government to step in and offer lifelines. The stakes could not be higher: These smaller employers account for 99.8% of registered companies in China and employ 79.4% of workers, according to the latest official statistics. They contribute more than 60% of gross domestic product and, for the government, more than 50% of tax revenue. In short: they are the beating heart of China’s economy.

Companies like Lau’s that have resumed some production are the lucky ones. Many factories and other businesses remain completely stalled due to the virus. Many owners have no other choice but pray that things return to normal before they careen off a financial cliff.

And here is the stark reality of China’s T-minus 3 months countdown: 85% of 1,506 SMEs surveyed in early February said they expect to run out of cash within three months, according to a report by Tsinghua University and Peking University. And forget about profits for the foreseeable future: one-third of the respondents said the outbreak is likely to cut into their full-year revenue by more than 50%, according to the Nikkei.

“Most SMEs in China rely on operating revenue and they have fewer sources for funding” than large companies and state-owned enterprises, said Zhu Wuxiang, a professor at Tsinghua University’s School of Economics and Management and a lead author of the report.

The problem with sequential supply chains is that these also apply to the transfer of liquidity: employers need to pay landlords, workers, suppliers and creditors – regardless of whether they can regain full production capacity anytime soon. Any abrupt and lasting delays will wreak havoc on China’s economic ecosystem.

“The longer the epidemic lasts, the larger the cash gap drain will be,” Zhu said, adding that companies affected by the trade war face a greater danger of bankruptcy because many are already heavily indebted. “Self-rescue will not be enough. The government will need to lend help.”

So where are we nearly two months after the epidemic started? Wwll, as of last Monday, only about 25% of people had returned to work in China’s tier-one cities, according to an estimate by Japanese brokerage Nomura, based on data from China’s Baidu. By the same time last year, 93% were back on the job.

And making matters worse, as we first noted several weeks ago, local governments around the country face a daunting question of whether to focus on staving off the virus or encourage factory reopenings, as the following tweet perfectly captures.

Banner 1 says: “If you go out messing around now, expect grass on your grave to grow soon.“ Banner 2 says, “Sitting at home eats up all your have, hurry up go out & find a job.” The slogan changes as frequently as they change the criteria for #COVID19 diagnosis. #coronavirus pic.twitter.com/2VnB5jZ0zz

— 曾錚 Jennifer Zeng (@jenniferatntd) February 23, 2020

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

As long as the national logistics network “is still in shambles,” Nomura’s chief China economist, Lu Ting said, there might be little to gain from rushing restarts, whereas “the cost of a rebound in infections might be quite high.” He expects economic activity to pick up again in a couple of months, although the longer Beijing fails to confidently put an end to the pandemic, the longer it will take for activity to return to normal. Meanwhile the 3 month countdown clock is ticking…

Don’t tell that to Zhou Dewen, the chairman of the Small and Medium Business Development Association in the city of Wenzhou, who knows this and agrees that this crisis is worse than SARS. Far, far worse. In fact, he said, it is “the most severe” of any crisis in the 40 years since China embarked on major economic reforms. He sees not a double but a “triple whammy,” factoring in the economic slowdown the country was experiencing even before the trade conflict and the virus.

Wenzhou, on the coast of Zhejiang Province, was the first city outside Hubei put into full lockdown in an attempt to stop the pathogen. As of last week, Zhou said, only factories that produce medical supplies had been allowed to resume work.

“What entrepreneurs need is confidence,” Zhou said. “But first they need to survive.” He is hoping the government will offer fiscal support and tax breaks to buy more time for small businesses. Some local governments have already responded to such pleas by waiving electric bills and delaying taxes, social security payments and loans. But for some businesses, such relief measures are little consolation.

Worse, last Sunday the communist party’s mouthpiece, the Global Times, suggested that instead of waiting for fiscal bailouts, Beijing will have no choice but to cut spending and unleash austerity, a move that would have catastrophic consequences for China. But even if Beijing does ease fiscally, it is unclear just what it can do short of printing money and handing it out to everyone. “A tax reduction doesn’t help if you don’t even have income,” said Zhu, who must somehow scrape together around 700,000 yuan ($100,000) for rent and the salaries of about 40 employees.

Zhu reckons her company will lose about 3 million yuan in profit over the two months. Besides the postponements, couples that were looking at wedding options before the outbreak have put their planning on hold. There is little room, it seems, to think about love in the time of the coronavirus.

“This is the most difficult time I have ever experienced” after 11 years of running the company, Zhu said. The worst part might be the uncertainty: She has no idea when the authorities might lift the ban or whether she can make it that long. “All of this is unknown to us,” Zhu said.

She is not alone: Wu Hai, owner of Mei KTV, a chain of 100 Karaoke bars across China, took to the nation’s premier outlet of discontent, social media platform WeChat, to voice his despair. KTV’s bars have been closed by the government because of the virus, choking off its cash flow. The special loans from the authorities will be of little help and no bank will provide a loan without enough collateral and cash flow, he said on his official WeChat account earlier this month. On WeChat , Wu gave himself two months before he has to shutter his business.

* * *

It’s not just Japan’s flagship financial publication and owner of the Financial Times, the Nikkei, that is dramatically changing the narrative away from “all shall be well.” In its headline article today, Bloomberg writes that “Millions of Chinese Firms Face Collapse If Banks Don’t Act Fast” and described the plight of Brigita, a director at one of China’s largest car dealers, who is also running out of options. Her firm’s 100 outlets have been closed for about a month because of the coronavirus, cash reserves are dwindling and banks are reluctant to extend deadlines on billions of yuan in debt coming due over the next few months. There are also other creditors to think about.

“If we can’t pay back the bonds, it will be very, very bad,” said Brigita, whose company has 10,000 employees and sells mid- to high-end car brands such as BMWs. She asked that only her first name be used and that her firm not be identified because she isn’t authorized to speak to the press. With much of China’s economy still idled as authorities try to contain an epidemic that has infected more than 75,000 people, millions of companies across the country are in a race against the clock to stay afloat.

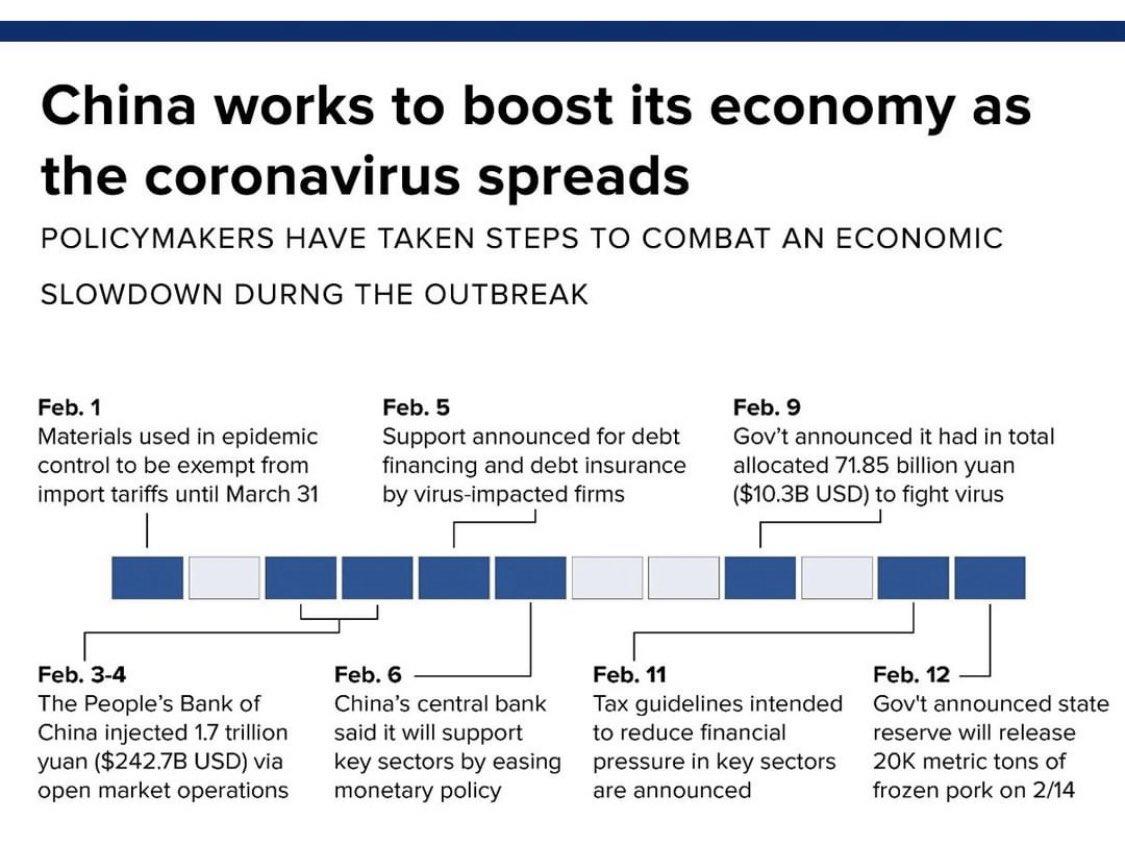

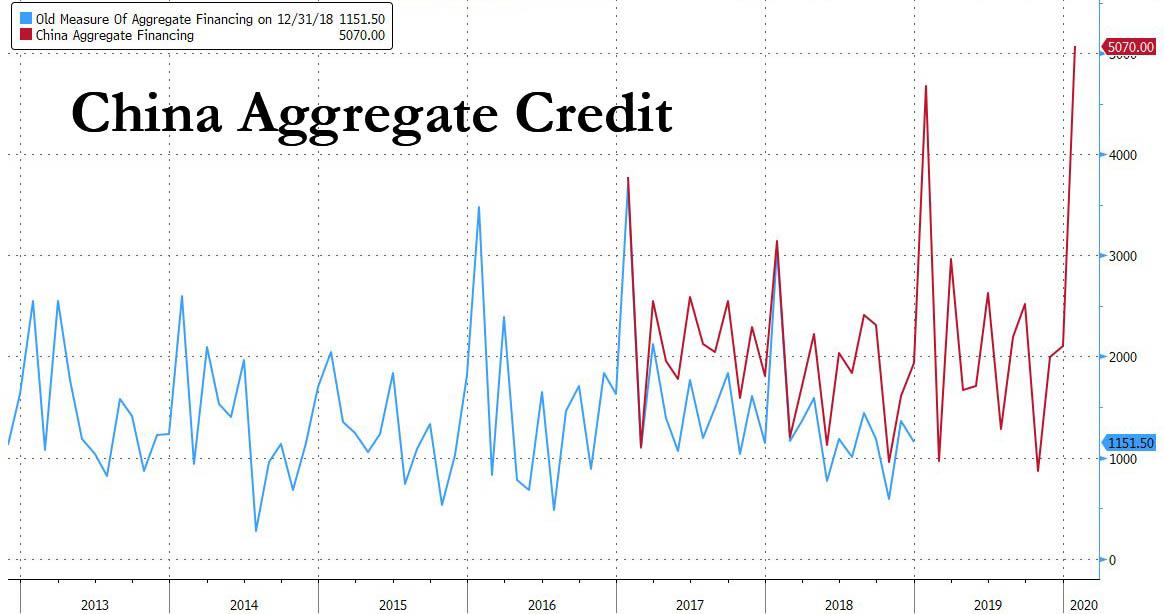

The irony, of course, is that all this is happening even as China has in fact eased dramatically in recent weeks, from cutting rates, to engaging in a barrage of mini stimulus measures, to injecting massive amounts of liquidity, to cutting taxes, to supporting virus-stricken companies…

… to flooding the economy with a record 5 trilion in loans and shadow debt in the last month.

Yet while China’s government has cut interest rates, ordered banks to boost lending and loosened criteria for companies to restart operations, many of the nation’s private businesses say they’ve been unable to access the funding they need to meet upcoming deadlines for debt and salary payments. Without more financial support or a sudden rebound in China’s economy, some may have to shut for good.

“If China fails to contain the virus in the first quarter, I expect a vast number of small businesses would go under,” said Lv Changshun, an analyst at Beijing Zhonghe Yingtai Management Consultant company.

Said otherwise, unless China reboots its economy, it faces an economic shock the likes of which it has never seen before. Yet it can’t reboot the economy unless it truly stops the viral pandemic, something it will never be able to do if it lies to the population that the pandemic is almost over in hopes of forcing people to get back to work. Hence the most diabolic Catch 22 for China’s social and economic system, because whereas until now China could easily lie its way out of any problem, in this case lying will only make the underlying (viral pandemic) problem worse as sick people return to work, only to infect even more co-workers, forcing even more businesses to be quarantined.

Some, like Bloomberg, blame the banks.

As a group, Chinese banks had offered about 254 billion yuan in loans related to the containment effort as of Feb. 9, according to the banking industry association, with foreign lenders such as Citigroup Inc. also lowering rates. To put that into perspective, China’s small businesses typically face interest payments on about 36.9 trillion yuan of loans every quarter.

In an emailed response to questions from Bloomberg News, ICBC said it has allocated 5.4 billion yuan ($770 million) to help companies fight the virus. “We approve qualified small businesses’ loan applications as soon as they arrive,” the bank said

Alas, it is not that simple: as we explained two weeks ago in “China’s Banks Face $6 Trillion Coronavirus Cataclysm If Epidemic Is Not Contained Soon“, China’s banks are rapidly retrenching well-aware that they face an explosion in bad debt as the bulk of Chinese companies face collapse. As such, it makes little sense for them to throw good money after bad, and instead most are hunkering down in anticipation of the coming shock.

Indeed, as even Bloomberg concedes, banks are hardly any better off themselves: “Many are under-capitalized and on the ropes after two years of record debt defaults. Rating firm S&P Global has estimated that a prolonged emergency could cause the banking system’s bad loan ratio to more than triple to about 6.3%, amounting to an increase of 5.6 trillion yuan.”

The bottom line is that for both companies and their bank lenders (and sources of potential rescue financing), there is one commodity in very short supply: trust. Trust that the counterparty will do the right thing; trust that the government will treat everyone fairly instead of just bailing out a handful of connected politicians. Trust, which in China in general has been lacking for years, as the formerly communist country succumbed to crony hypercapitalism with Chinese characteristics, one in which knowing who to bribe and who to lie to meant the difference between success and failure. Trust was never cultivated. And now that lack of trust is about to cost China dearly.

In any case, the lack of far more funding means that China’s smaller businesses whose revenue have suddenly collapsed, have just weeks if not days of liquidity left. Brigita, whose firm owes money to dozens of banks, said she has so far only reached an agreement with a handful to extend payment deadlines by two months. For now, the company is still paying salaries. But those will stop too.

And that’s when the real crisis begins as hundreds of millions of workers suddenly find themselves unemployed.

For some the crisis has already begun. Wang Qiang, a 23-year-old migrant worker, has been unable to find work in Shenzhen after three weeks of searching. On top of the limited factory job openings, the Nikkei notes that he faces another major obstacle: his identification labels him a native of Hubei.

His home province, where the virus originated, accounts for the vast majority of the 74,000-plus mainland infections and most of the deaths. “The labor dispatch companies told me that the factories don’t want people from Hubei,” he said. The fact that he did not go home for the Lunar New Year holidays seems to make no difference.

Wang spends his nights sleeping on the floor of an uncompleted building. “I’ll wait and see if the situation gets better when companies restart work on Feb. 24.”

In a few short hours Wang will be greatly disappointed. He won’t be the last one, however, and if China’s doesn’t find some miraculous solution to the current coronavirus crisis, in two months China will face a financial, economic and social cataclysm the likes of which it has never seen in its modern history.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 02/23/2020 – 14:45![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com