“Ich Bin Ein Berliner”? Germany’s “Donut Disturb” Economic Problem

By Michael Every, Global Strategist, Elwin de Groot, Head Macro Strategy, and Erik-Jan van Harn, Macro Strategist at Rabobank

Summary

- In 1963, US President JFK stood behind Germany, saying “Ich bin ein Berliner!

- Europe now risks another potential bifurcation, and sides need to be taken once again

- Germany’s economic role has, like a ‘Berliner’ jam donut, been sweet for decades

- However, the more illiberal world is forcing liberal Germany to either change or be changed

- We plot four paths –and donuts– for Germany’s future and their economic and market impact: regrettably, none are as sweet as the current model, but some have far less jam

- The path/donut that Germany chooses will have huge ramifications for both itself and the EU for years to come

“Ich Bin Ein Berliner”

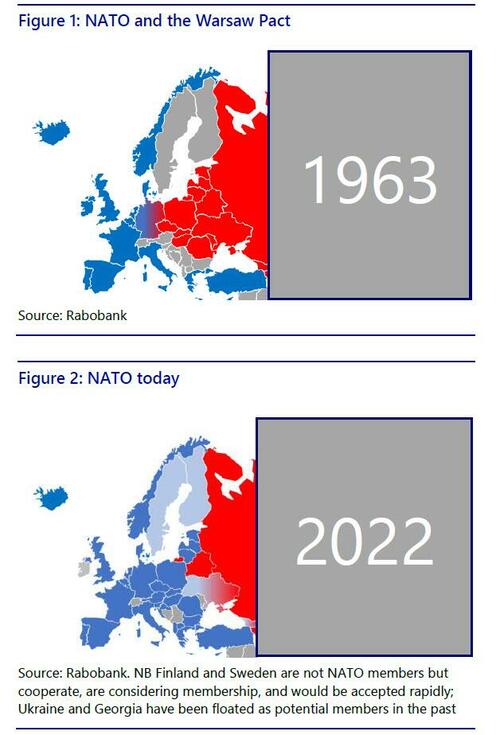

In June 1963 the Berlin Wall divided that city and Germany and Europe were split between a Russian-east and a US-backed west (Figure 1). US President Kennedy stood before a huge crowd in West Berlin and stated: “Ich bin ein Berliner!” Urban legend says he misspoke by calling himself a jam donut (also a ‘Berliner’), but he didn’t: his historic speech underlined the firm US commitment to West Germany and Western Europe.

After the end of the Cold War Germany and Europe was mostly reunified and at peace: the EU and NATO expanded in tandem (Figure 2) all the way to Russia’s borders.

However, Russia attacked Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, and Europe stands on the brink of the largest military action since WW2 over Ukraine again. Russia demands a new European security architecture that gives it a large role and the US a far smaller one. Worse, Russia and China have declared a global alliance to support each other’s positions. Europe risks another potential physical, economic, financial, and political bifurcation.

Enormous decisions loom for the EU – and Germany as its heart. The US stood with Berlin during the Cold War: will Berlin stand with the EU and US now? We will show that doing so means Germany could lose the economic jam from its current donut; yet thinking only of Berliners risks making Germany the hole in an economic ring donut.

Map of Europe on the Table?

To underline the scale of the crisis playing out, former politician Bruno Maçães writes in Time: “What Happens Next in Ukraine Could Change Europe Forever”.

He repeats an argument we have made since 2017: “We no longer live in the old liberal order where rules must be enforced, and violators punished. We live in a new order where power must be balanced with power…

The US must reflect on whether it can afford to reduce its presence in Europe before a proper counterweight to Russia has been created in Brussels. The pivot to Asia may need to wait for a solution to the European crisis. As for Europeans, they need to quickly prepare themselves for a new world, where their sovereignty and security may well be at stake…

The existing order is starting to buckle, and Washington needs to decide how best to replace it with new arrangements. Does it prefer to reach a grand bargain with Moscow whereby the two powers divide Europe among themselves? Or does it prefer to encourage and support the development of a new European pole capable of balancing Russian power?”

In short, massive geopolitical decisions are being taken – and potentially above Europe’s head.

Maçães concludes: “To me the choice seems an obvious one, but what is frustrating about the current crisis is how we keep avoiding the larger questions of political order. By hesitating we allow others to assume the role of reformers and innovators. Eurasia, the supercontinent, is being reshaped before our eyes.”

Indeed, this is a global metacrisis. The West is economically weak and politically divided; Afghanistan recently saw the US exit in dramatic fashion; China is looking at Taiwan; and China and Russia are developing sanctions-resistant financial infrastructure, meaning Western sanctions on Russia would need to be extended to China.

Indeed, the Foreign Policy Research Institute repeat that: “Beijing,…in a crisis might conclude it has no choice but to stand up to America’s extraterritorial sanction power. If so, Russia would find a valuable friend amid the crisis – and the West could find itself embroiled in a two-front financial war.” The US is now warning of that outcome too – and some fear a two-front physical war that the US cannot easily fight given the present array of forces.

Germany is already being dragged into a spat with China over Beijing’s treatment of Lithuania: far worse may be to follow.

No Tools in the Toolbox

Germany helped the EU deal with the Eurozone Crisis of 2012-13 and the Refugee Crisis of 2015 (both of which it also arguably helped drive), as well as Brexit in 2016. However, Russian pressure on Ukraine and eastern EU members represents a problem Berlin cannot readily solve using any of its traditional methods or policies of mercantilism and pacifism.

Germany chooses to play a passive geopolitical role to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. The current government’s stance so far reflects public opinion. In a recent survey, 73% of Germans were against delivering weapons to Ukraine; 57% think Russia won’t invade Ukraine; and 55% think they can rely on Russia to keep gas flowing despite the crisis.

Germany has no military strength. Back in the 1980s, West Germany had a powerful army. United Germany presumed it had no need to do so because Europe was at peace, and it sat under the US-backed NATO defence umbrella. However, we are clearly back to Great Power struggles globally. The US, increasingly focused on Asia, is not the relative superpower that it once was, and now faces a two-front challenge from Russia and China across both Europe and Asia.

Germany has huge fiscal resources but remains wedded to low government debt. This naturally reduces all its options in a crisis – or gives it huge options if it pivots.

ECB monetary policy is no use against a military threat. It could help only in conjunction with fiscal policy, to pay for higher defence spending. Yet war and/or sanctions on Russia/China would push German inflation much higher.

Germany is vulnerable on the import side due to reliance on Russian gas and the shut-down of its nuclear power.

Germany is vulnerable on the export side given net exports are a key GDP driver.

Unlike with Brexit, Russia is deliberately exacerbating these pre-existing differences within the EU and NATO rather than allowing unity against an external opponent.

Notably, while much of the West has rallied behind Ukraine, Germany has prevaricated. Berlin has wavered over imposing harsh sanctions; rejected sending even defensive arms to Kyiv; stalled EU efforts to send arms too; and will not spend more on its own defence regardless of longstanding US complaints. This is seeing rising tensions between Berlin and parts of the EU, even if the US is opting to downplay its own concerns in public.

Liberalism vs. Freedom

Russia is touching on member states’ deepest interests. For Germany this is usually economic, while for others it is now about national security. Sweden and Finland, the three Baltic states, Poland, Slovakia, Czechia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Romania all look at developments in Ukraine and the Balkans and feel existential threats: war on their borders; economic disruption; refugee flows; and if not outright invasion today, then potential Finlandization by Russia in the future. This transcends –and exacerbates– pre-existing EU differences along the dividing lines of EU vs. Eurozone, Eurozone core vs. periphery, as well as East-West geographical and cultural splits. Spats over rule of law are one thing: this is the law of the jungle.

As academic Timothy Garton-Ash writes: “If, faced with an aggressor who is prepared to use violent means to destabilise and dismantle a European state, you refuse to supply defensive weapons to Ukraine and rely only on OSCE monitors and diplomatic negotiations, you are in effect conceding Yalta while pretending to do Helsinki. You are making war more probable by failing to defend peace…[and the] muddled thinking, self-deception, and outright hypocrisy that this entails.” More conservatively, the German Council on Foreign Relations (DCGP) reports: “…for many allies, Germany seems to be once again a weak link and an unreliable partner in European defence.”

The fundamental duty of every state is to defend its territorial integrity and national sovereignty: the EU and NATO must be able to provide such structures or else they risk being superseded by new ones that do.

Yet that comes at a cost. Since 1945 and 1991, Germany has mightily benefited from the current Western architecture at relatively little cost: it has been the ‘jam’ in a European jam donut. However, things now need to change dramatically if Germany is not to become the hole in a European ring donut over time.

There are two easy ways to measure that German jam.

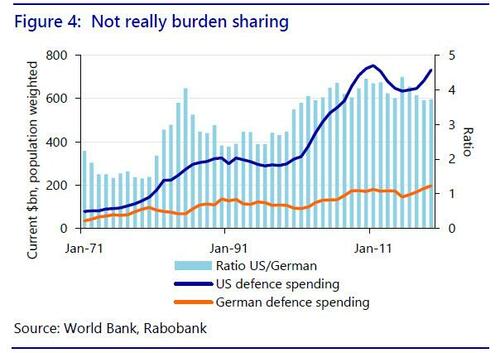

First, defence spending. If looking at US vs. German expenditure on a population-adjusted basis, the gap is obvious (Figure 4). The US spends almost 4 times more per person on defence than Germany does – and the results are clear in this crisis. The cumulative difference is $10.5 trillion since 1991. Germany would not need to spend that much given it is not trying to be a global hegemon. However, relying on the US umbrella has unarguably saved Germany vast sums: 20% of the gap would equal EUR 1.8 trillion, or EUR60bn annually since the end of the Cold War.

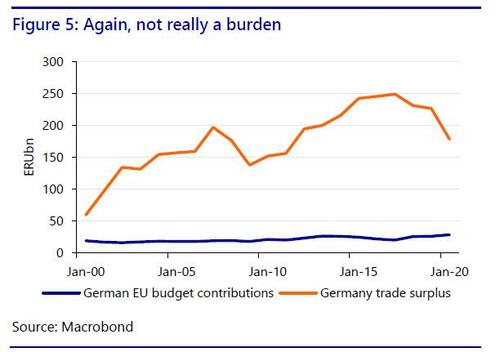

Moreover, while Germany is a generous (net-) contributor to the EU budget (Figure 5), the exchange-rate benefit it gets from being in the Euro –the overall lower exchange rate it enjoys compared to where it would be if it still had the Deutschemark– more than compensates in terms of its persistently large net export surplus.

Jam today, as they say, and for the last 30 years. However, while liberal Germany has not changed, the world has – in a far less liberal direction. As such, Berlin now needs a new economic model – and if it doesn’t choose one, one will be forced on it anyway. Either way, Germany, and the EU, are in for huge changes.

The Journey to the…?

We see four potential roads Germany can go down ahead:

- Muddle through, trying to please all sides and evade geopolitical confrontation as much as possible; a scenario that we will call “Status quo”.

- Re-align with the current EU/NATO architecture; a scenario that we will call “(Re)turning westwards”.

- Act in similar fashion, but on a pan-European basis without the US; a scenario that we will call “Strategic autonomy”.

- Actively choose to appease Russia and China; a scenario that we will call “Turning eastwards”.

We will now run through a broad description of each of them before then contrasting the impact each would have on the level and composition of German GDP growth, as well as on trade patterns, fiscal and monetary policy, the exchange rate, and intra-EU cohesion indicators such as Eurozone sovereign yield spreads.

1. “Status Quo”

Germany could try to muddle through with its current pacifist and mercantilist policies. Although that may limit economic damage in the short run, in the long run it could damage external European stability as well as cohesion. The path of least resistance in the near term is not without huge tail risks!

As Ivan Krestev now puts it in the New York Times: “Germany has not changed – but the world in which it acts has. The country is like a train that stands still after the railway station has caught fire.” We argued something similar.

Without clear EU crisis leadership, which requires Germany on board, countries could choose to work around Brussels; and if Germany does not play an active role in the EU’s defensive shield, NATO, then other member states may again choose to work around it and form new arrangements.

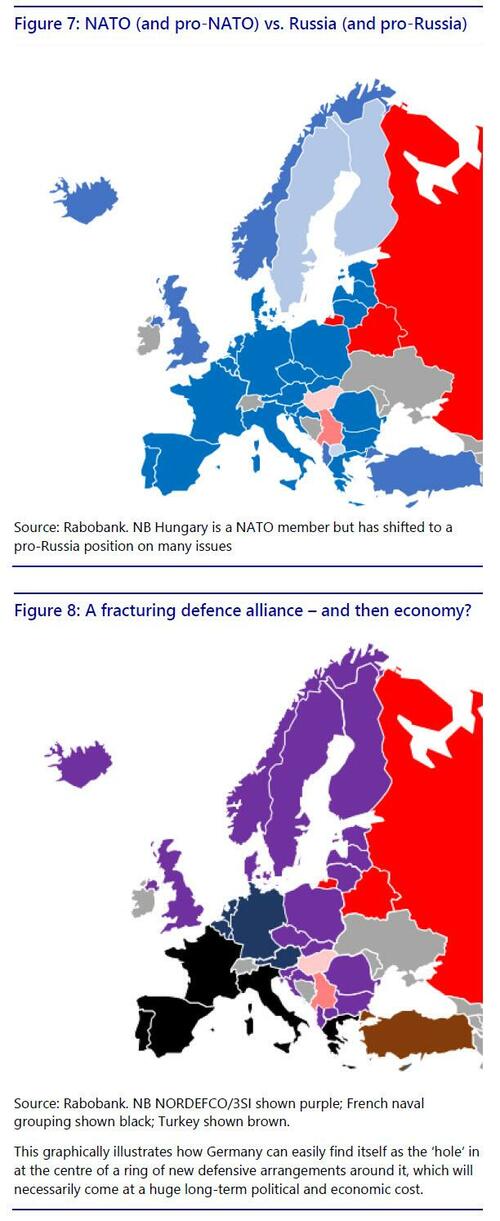

We already see signs of the latter happening. US generals are calling Polish, not German counterparts first; Poland is to double the size of its army; the UK to sign a defence treaty with Poland and Ukraine; Scandinavian states, the UK, and the Baltics are co-operating more closely through the NORDEFCO defence grouping; Romania is asking for more US F-35s; the US is backing the Three Seas Initiative running from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea and Mediterranean, and under former President Trump threatened to walk away from NATO; France is building Mediterranean ties with Italy, Spain, and Greece; Turkey is increasingly acting independently outside of NATO; and Hungary seems to be more pro-Russian than pro-NATO in this crisis. Germany is out of all these loops (see Figures 7 and 8).

Further inaction from Germany will see these cracks in the European defensive foundations becoming pronounced in the economy over time: and where defence leads, trade will eventually follow – that dynamic built the EU. ‘Hunters eat first’ traditions also imply new intra-EU powers for those with more muscles.

Ironically, a political stance that aims to maintain the status quo actually leads to its erosion: no less irony than that of Vegetius, who stresses Si Vis Pacem, Para Bellum (“Let he who desires peace prepare for war.”)

The status quo is therefore likely to see trust in EU and NATO cohesion erode, leading to higher peripheral Eurozone spreads – a single measure representing a broader divergence in economic performance and inflation in the long run.

2. “(Re)turn Westwards”

In this scenario, Germany embraces realpolitik. A clear commitment to the West and NATO will lead to even closer cooperation within the EU (closer to a political union) and with allies such as the US and the UK. However, there will be a strong bifurcation between the West and the East, much like we saw during the last Cold War.

A strong military will also be required. This major step towards European autonomy will cement the foundations of the Union and pave the way towards further integration along defence supply chains, economically, and national security trust, politically. International trust in the EU would also rise and, as a consequence, risk premiums such as peripheral spreads remain sustained at low levels, or fall.

This does come at a heavy price, however. There are direct up-front costs, such as far higher defence spending. Germany currently spends just 1.3% of GDP, and much of that is not directed to front-line equipment. The US and Russia both spend closer to 4% of GDP, and during the 1980’s Cold War the US figure was over 6%, and during the 1960’s, nearly 10%. As another example, Israel today spends 5.6%.

While the US might appreciate Germany finally meeting the previously mooted 2% of GDP NATO commitment, this was a ‘peace-time’ goal before Russia (and China) changed the European and global equation. Germany would need to at least match the US and Russian 4% of GDP military spending level, and maintain it for decades, to truly allow its military to catch up with Russia’s and so help support the US on the European front.

Given not all of these costs can be financed via an off balance-sheet investment vehicle, the extra 2.7% of GDP required would either mean deep cuts to other government spending or abandoning the Stability and Growth Pact’s fiscal limits – and across the EU, not just for Germany. That would be a real economic game-changer, and would initially face domestic opposition given the entrenched fear of inflation against the current backdrop.

Ironically, just as the US is now pushing Germany to spend more on defence, under this scenario Germany would probably then push other EU member states to spend the extra budget only on defence too, rather than social programs, etc. That would point to the deeper political cooperation inherent in this scenario.

Moreover, while Germany has the required technologies, and is already an arms exporter, it is unlikely it will be able to manufacture all the required defence equipment domestically, so imports would surge, presumably from the US, NATO’s key arms producer. Simultaneously, the production capacity reserved for defence equipment will crowd out the production of export goods, reducing export opportunities.

Germany would also see a sharp decline in exports to Russia and China, which currently make up roughly 7% of the total. It is unlikely that this loss could easily be absorbed by EU countries given Germany already has a large trade surplus with most of them – unless Germany produces more arms to sell them.

Energy security would be a challenge as well. Choosing to fully (re-)engage with the West would force Germany to seek energy outside Russia. An obvious option would be to restart the nuclear power plants, or to increase domestic production of coal (which would obviously clash with the green ambitions of the EU – underlying how geopolitics cuts through apparently domestic policy debates). However, it is very unlikely that Germany could become energy independent.

Gas imports from the US or the Middle East would therefore be necessary to fill the gap – but given Russian and Chinese interests in the Middle East, would again require a more ‘muscular’ EU presence. Notably, Germany does not currently possess LNG gas terminals to receive such shipments, underlining the scale of the challenges being proposed and the limited near-term room for manoeuvre.

The monetary policy response to this huge economic shift is hard to predict: however, once national security moves to the economic and political forefront, normal inflation-fighting strategies move to the background. We already saw an echo of this in the initial response to Covid-19 and the current energy crisis.

The flow-through effect to the exchange rate is ambiguous. Looser monetary policy would weaken the euro, but stronger cohesion in the EU could provide support.

3. “Strategic Autonomy”

A parallel scenario would see Germany shift away from the US and Russia in conjunction with EU partners – the so-called path of “Strategic autonomy”. This might be a deliberate choice, or taken in response to a future US decision to step back from European security.

The imperative for greater EU political coordination would hold truer, and the impetus on higher defence spending would be even higher. However, there would not be the same willingness to import armaments from the US. Instead, Germany would look to its and European suppliers, most notably France.

An extra 3-4% of GDP on EU-sourced defence goods would obviously see an even larger shift in production and consumption vs. exports – and inflation. The ECB would likely have to act. However, historically, rapid rearmament often sees controls over market pricing to help allocate key resources, e.g., price controls, rationing.

The trade impact would be mixed in that export opportunities would have to be passed over in favour of domestic consumption; and a ‘fortress Europe’ would find itself in realpolitik trade tussles with the US and Russia/China – and indeed, almost everyone in an even more zero-sum world.

Europe would also still find itself grappling with its underlying vulnerabilities over a lack of domestic energy (priced in dollars), its lack of physical control of supply chains, of the inputs for green technology, its lag in tech sector to date, and the often-overlooked Achilles Heel of its reliance on the US-centric Eurodollar system (previously covered in detail here).

In short, while perhaps superficially attractive, this path would be fraught with risks.

4. “Turn Eastwards”

Germany could also choose to fully embrace the East, reviving and reinventing Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik. Although it is still bound by European law, and therefore unable to negotiate any trade deals with non-EU countries, Germany could cooperate with Russia and China on specific projects in industry, energy, and technology, just as they did with Russia on NordStream 2. Additionally, Germany could frustrate the EU’s potential foreign policy shifts on China and Russia in order to favour Moscow and Beijing.

Obviously, there would be no EU cohesion here unless Berlin could drag the rest of the EU with it – which would almost certainly not be the case for eastern members. Germany would also no longer be seen as an ally by the US.

True, there would be no need for Germany to spend more on defence, meaning no need for fiscal stimulus. However, the net effect on the economy would not be positive given that although trade with China and Russia would increase slightly –if not on Germany’s terms, with imports rising more than exports– this would not be enough to offset a predicted sharp decline in intra-European trade and exports to the US.

Poland for example, has already opted to import gas via a pipeline from Norway, rather than Russian gas imported through the German Nordstream2 pipeline. If Germany looks east, could the current deep bilateral economic integration remain true over the long term? We believe true Ostpolitik would isolate Germany from the rest of Europe and could turn small cracks into a large fissure in the EU’s foundation.

This could also have significant economic consequences for the Union. More uncertainty regarding European cohesion would raise peripheral spreads, whilst investors may shun the euro to prevent getting caught in the political crossfire.

Only a little imagination is required to see how one could compare this scenario to the Euro crisis, when investors questioned the viability of the Euro project. The euro lost as much as 20% of its value against the dollar at that time, whilst peripheral spreads for most Southern European countries rose to 6%.

Such a development would put the ball into the ECB’s court, but EU fissures might travel in its direction. In this scenario, why would Germany continue to support policies that favour the EU’s most indebted member states? Or would it require them to look east too as a quid pro quo for support? One can see how geopolitical this would rapidly get – and then add in the risks from the US Eurodollar system again on top.

‘Donut Disturb’

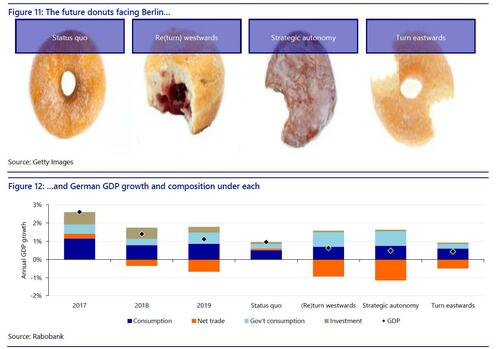

While Germany really wants to say ‘donut disturb’ to the world, its economic jam donut is going to be disturbed. In each of the four scenarios just described, the presumed rate of German GDP growth will differ markedly and the composition of GDP by demand will change with it, with some sectors benefiting and others losing out. To help simplify this categorisation we have also shown what new kind of donut they represent.

“Status quo” is a ring donut rather than the current jam-filled one because of the risks that we have already flagged of a gradual, and perhaps more rapid than forseen, collapse in EU and NATO cohesion. In this scenario, we project German GDP growth at 1.0% y/y as compared to 1.1% in 2019, but with risks clearly to the downside over time.

“(Re)turn westwards” is a jam donut…but one with a large bite taken out of it, or at least much less jam than before. The headline level of GDP growth is seen at 0.6%, around half of the level in 2019. Moreover, the composition of growth shows a marked shift, with net exports a much larger drag than normal and government (military) consumption a much larger share.

“Strategic autonomy” is a glazed jam donut, so loaded with sweetness –but potentially to the point where it causes economic diabetes– and with a large bite taken out of it. Inflation may soar in this scenario, but the huge disruption to the economy would likely see real GDP growth fall further vs. the previous trend, to just 0.5%. Moreover, the GDP composition changes even more compared to 2019, with even higher state spending and even more of a drag from net exports.

“Turn eastwards” is a ring donut because of the risks already flagged in walking away from the US and much of the EU. The scale of this economic and financial disruption shows a donut with two bites taken out of it. GDP growth in this scenaro is seen at just 0.4%, so almost a third of the 2019 total. There is no fiscal boost at all. There is therefore also no major drag from net exports assumed – but that could be an optimisic assesment if the EU and the US reject or tariff German goods, and Russia and China do not buy more to compensate.

Market Impact

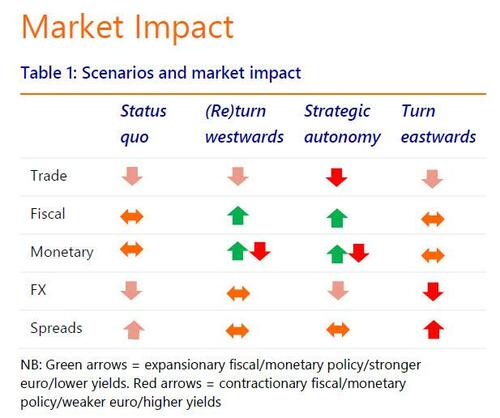

Beyond headline GDP, the presumed market impact of the four ‘donut’ scenarios are shown above in Table 1.

In terms of German trade, already partially captured via net exports in GDP, “Status quo”, a “(Re)turn westwards”, and a “Turn eastwards” are all negative compared to the pre-Covid norm. “Strategic autonomy” is far more negative than before.

In terms of German fiscal policy, “Status quo” and a “Turn eastwards” see net state spending unchanged, while a “(Re)turn westwards” and “Strategic autonomy” both see large fiscal expansion.

On monetary policy, or at least the German contribution towards it, “Status quo” and a “Turn eastwards” again see little for the ECB to worry about: yet a “(Re)turn westwards” and “Strategic autonomy” would both suggest either the ECB would need to raise rates faster given a vastly more stimulative fiscal policy, unless government price controls or industrial policy helped to ameliorate the inflationary effects; OR to lean towards some de facto form of fiscal-monetary support, e.g., by accepting that defence spending also qualifies for ECB bond purchase schemes. This would presumably also mean some form of financial repression. Over time, that could still mean ‘easy’ policy followed by ‘tightening’ policy, hence the green and red arrows.

On the FX front, “Status quo” and “Strategic autonomy” both imply a drift towards a weaker euro, at least short term, and a “Turn eastwards” a much weaker one, while a “(Re)turn westwards” would more neutral.

Regarding intra-EU yield spreads, “Status quo” sees spreads widen, and a “Turn eastwards” to spike; “Strategic autonomy” and a “(Re)turn westwards” would be neutral.

Mr. Donut

As the reader may have gathered, no future scenario is as sweet for Germany as things were until the Ukraine metacrisis started. But some clearly have less jam than others.

Regrettably, having failed to address the changing geopolitical reality over the past few decades means there is now going to be a high price for Germany to pay. It may be a heavy burden for the country that played such a key role in the post-WW2 economic build-up of Europe – but no other European country can do it.

We do –perhaps– see some movement from Germany already: but against China, not Russia. It is reported that:

- Chancellor Scholz is to prioritize engagement with democratic partners in the Indo-Pacific instead of China.

- Fully supports Lithuania against Chinese coercion, which the EU (and Australia and the UK) have already taken to the WTO.

- Foreign Minister Baerbock will be allowed to champion initiatives against China, and German diplomats in the Indo-Pacific are “being encouraged to push the envelope and resist old habits to self-censor” when developing new China strategies; and

- Germany is reportedly to declare China a “systemic rival” narrowing the EU’s confused troika of that tag as well as “partner” and “competitor” down to just one.

Obviously, this will exacerbate German-China economic tensions, and please the US. However, that still appears the bare minimum this US administration would expect rather than a German quid pro quo for ongoing US security: the US won’t change its pivot to Asia. In NATO and EU eyes, Germany must still do far more, now. It must also accept the risk of economic pain via sanctions, and certainly not block others from acting over Article 5, if needed.

After all, if you decided to turn your economy into your powerbase rather than into weapons, like Germany has, then it still involves taking hits for your allies: armies take damage in wars – economies take damage during economic wars.

In short, Germany must make an existential decision: to look westwards to the US again, and fill its defence gap; to look inwards at the EU, and fill its defence gap; to look eastwards to Russia, and not fill that gap; or to look away entirely, and face the consequences around it as others face up to the present crisis.

We will soon find out if Berlin are 1963 Berliners or not. The path Germany chooses will have huge ramifications for both itself and the EU for years to come.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 02/14/2022 – 03:30

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com