Life In The 1970s

Submitted by Nicholas Colas, founder of DataTrek Research

The economic history of the 1970s and early 1980s is getting a lot of attention these days as an analog to today’s period of soaring inflation (see our post from October “Is Stagflation Here: Comparing The 2020s With The 1970s“). For his latest Story Time note, DataTrek’s Nick Colas offers up 3 personal anecdotes to fill in some of the gaps on that fateful decade: food inflation was a huge issue, especially in the early 1970s. Second, unemployment was actually higher in the early 1980s than during the Financial Crisis. Third, Fed policy ran very differently from today, targeting money supply growth with dramatic swings in Fed Funds rates.

Some more details from Colas on Life in the 1970s:

#1: Going to the supermarket.

Once I turned 10 (which was in 1974), one of my household chores was to run errands to the local grocery store. My family lived in New York City, and the market was a short walk from our apartment. My mom gave me a list of things to buy, some cash, and sent me on my way.

On one such trip – I think it would have been 1975 – I got to the cash register with my items and a $10 bill. The cashier rang them up. The total was $11 and something.

“What do you want to put back?” the cashier asked. I had no idea. I had never come up short before. In the end she chose the lowest ticket items that would bring the bill down to below $10.

I walked home in shock. My family was not wealthy, but we had always had enough money to buy food and get change back from the transaction. What had just happened? Was it my fault?

That was my introduction to inflation. When I got home my parents thought I had been mugged, because I was so upset. They explained prices were going up a lot lately, and that’s just the way things were.

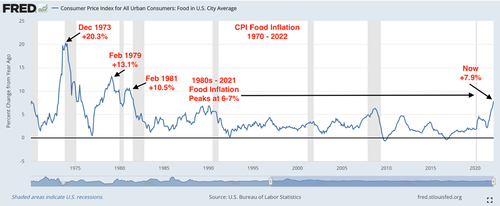

The chart below shows US CPI food inflation from 1970 to the present, and it shows just how different the world has been since then. The cost of food has risen most years since the early 1980s, but only in a band of 0 to 5 percent. Now, however, food inflation is 7.9%. That may not be back to the 1970s/early 1980s, but it is outside of the historical band since then.

Takeaway: when people say, “if you didn’t experience 1970s inflation, you don’t know how bad it can be”, food inflation is a big part of what they mean. Wages went up in the 1970s (+6-9 percent annually), just as they are now (+6-7 percent). But wages did not keep up with food prices then, and they are not doing so now. It is frightening, as a child or adult, to wonder if food prices will rise so quickly that you will only be able to afford the basics or even less. “What do you want to put back?” is an awful question to hear.

* * *

#2: “Your father is going to be a consultant, working for himself. He got fired.”

While the 1970s/early 1980s are now best known for inflation, they were also a period of very high unemployment and job insecurity. My own family went through that in the late 70s, when my father lost his job. He picked up work as he could, and we were OK eventually.

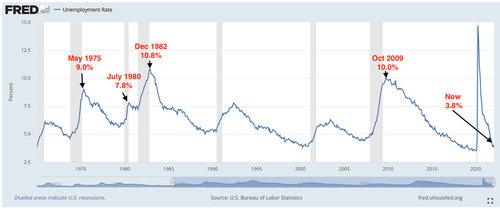

This chart shows just how bad US unemployment was in the 70s – early 80s. It never fell below 5.7% and was 8 – 11 percent during the 3 recessions of the period. At its worst in late 1982, unemployment got to 10.8 percent, higher even than the Great Recession.

Takeaway: with US unemployment now at just 3.8 percent, we are a long way from the 70s-early 80s experience. I do wonder how this will affect the Federal Reserve’s efforts to reduce inflation without causing a recession. At yesterday’s press conference, Chair Powell made it clear that his goal is to reduce the current labor market imbalance between openings (companies’ desire to hire) and unemployed workers (available labor supply). Cooling the economy through rate hikes should do that, but he and the Fed will have to strike a fine balance. The central lesson of then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s early 1980s rate hikes is that recession is the fastest way to reduce high inflation.

* * *

#3: “Watch the money supply”.

I first became interested in capital markets listening to the news in the morning before going to school. The local NYC station featured a fellow named Larry Wachtel at 7:55am every weekday morning. He was a market strategist before that was a popular job title, and he made the markets intelligible and even interesting to my teen aged ears.

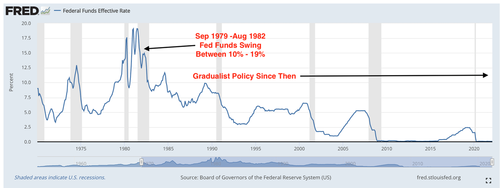

Larry would focus on the US money supply data to get an edge on market action. This was because in October 1979 Paul Volcker had made it a central focus of his fight against inflation. Back then, Fed policy was much more opaque. No post-meeting communiques, no press conferences, and no Fed-head interviews. Volcker needed to give investors a simple roadmap to explain the Fed’s goals. He chose the supply of money. Slow its growth, and lower inflation should follow.

This translated into both very high, but also very volatile, Fed Funds rates as the chart below shows. Volcker’s Fed, free of the communication requirements of today’s institution, moved Fed Funds aggressively and frequently to manage the supply of money by changing its cost as needed. It was shock therapy for the US economy, and it eventually worked.

Takeaway: where Paul Volcker’s Fed managed to a number (money supply) that it could directly influence by changing interest rates, Jay Powell’s Fed has chosen to strictly adhere to the “dual mandate” of measured inflation and unemployment. In 2020 – 2021, Chair Powell was fond of saying that the Fed has a great playbook for reducing inflation. Paul Volcker wrote that playbook, and it is expressed in the above chart. How much today’s Fed will follow it remains an open question. For clients interested in this topic, I recommend the link below. It summarizes Volcker’s inflation-fighting strategies and their costs on the US economy.

Sources: Paul Volcker and the US Money Supply: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/anti-inflation-measures

Tyler Durden

Sun, 03/20/2022 – 13:30

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com