Foreign Demand For US Treasuries Collapses Just As Fed Launches QT

With just days left until the Fed begins winding down its gargantuan, $9 trillion balance sheet, and as rates reset higher globally amid a growing panic that the Fed is so far behind the curve yields will soar much higher before inflation is contained, a problem emerges: investors have been increasingly focused on the risk of supply/demand imbalances in Treasuries, and are starting to freak out that there will simply not be enough foreign demand for US paper. It turns out, they are right to be worried.

As Goldman’s Avisha Thakkar writes, “the combination of a material reduction in negative-yielding debt, the diminished economic appeal of USTs versus domestic alternatives, and de-dollarization efforts by official institutions should see foreign demand wane in coming quarters.”

That said, two factors may mitigate the rates market impact in the near term:

- First, the combination of US supply and likely continued demand from other investors should attenuate supply/demand imbalances as foreign demand moderates.

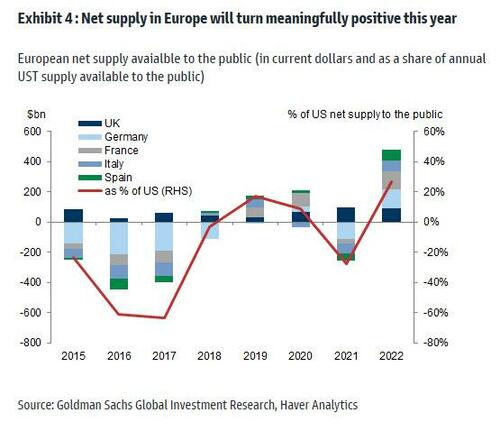

- Second, while European net supply available to private investors will swing positive this year given reduced ECB presence and rising deficits, free float will be rebuilding off very low levels and may therefore still be a near-term constraint on the set of viable alternatives to Treasuries.

A larger impulse to US yields would, in Goldman’s view, require either a faster rebound in free float, a further reassessment of global neutral rates, and/or a further upshift in EUR and JPY yield ranges. The latter could, for example, be driven by a resolution of the Russia/Ukraine war or a more decisive shift by the BoJ away from YCC — but not even Goldman expects either of these to take place in the near future.

But before we focus more on the consequences, let’s drill down some more on the core matter at hand: fading demand from that staple source of demand for US bonds over the past few years, foreign buyers.

To start, it’s worth exploring the foreign buyer base in greater detail. Overseas demand is typically split into two groups with distinct motivations for owning Treasuries: the private sector and the foreign official sector (which includes central banks, governments, and sovereign wealth funds).

- Foreign private investors’ considerations generally reflect a combination of rate differentials and currency movements, as they will buy on both an FX hedged and unhedged basis.

- Foreign central banks, in contrast, are less motivated by the expected return on Treasuries — instead, these flows can reflect liquidity/safe asset related demand or foreign exchange reserve management when intending to lean against significant currency moves. Indeed, foreign official holdings are sensitive to broad Dollar movements, though they are more responsive to structural trends rather than any short-term fluctuations.

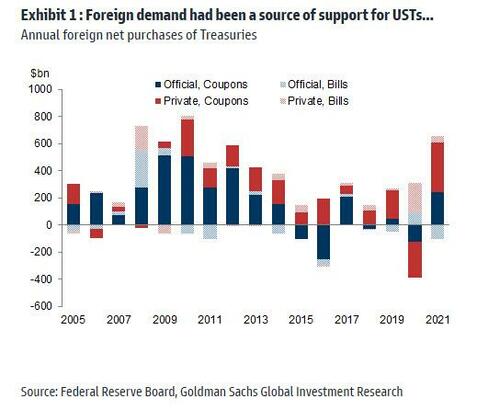

Last year, the majority of UST demand originated from private investors (Exhibit 1), though purchases from the foreign official sector turned modestly positive, supported by broad Dollar weakening.

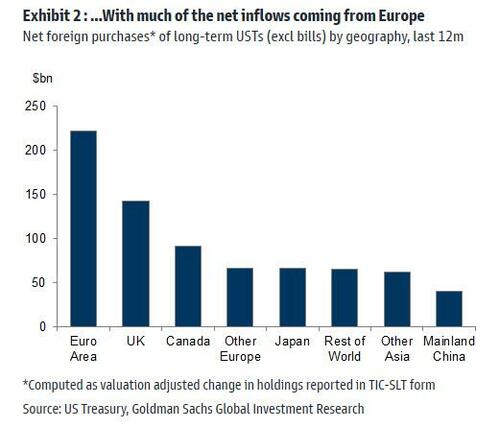

A geographic breakdown of UST demand, shown in the next chart, reveals European investors had been the marginal foreign buyer.

First, it’s worth acknowledging some of the flows could be driven by non-European demand showing up through financial centers (such as in the UK, Belgium, and Luxembourg). But for European investors, Treasury demand in part reflected a still substantial share of debt trading with a negative yield in the domestic market, likely deterring investors who did not want to incur potential capital losses from a longer holding period (which means that the ECB’s push to lift nominal rates positive may be a very negative development for US bonds). Further, a surge in domestic central bank buying of sovereign debt likely displaced private sector demand. It is also worth noting that European investors are the most clearly motivated by hedged yield spreads, which turned meaningfully positive last year. Over the next year, Goldman expects that “all three of these tailwinds to higher UST demand will unwind.” Needless to say, that’s not good for prices.

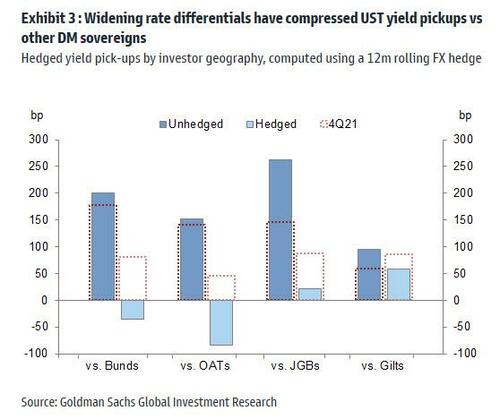

But one doesn’t have to wait until next year: already, the economics of investing in USTs has shifted meaningfully for FX hedged investors in large part due to the sharp rise in currency hedging costs as policy rate differentials between the US and other G4 markets have widened.

The chart below shows the compression in yield differentials when hedged for the currency risk of owning USTs. Assuming a 12-month rolling hedge, EUR hedged 10y USTs yield about 35bp and 80bp less than 10y Bunds and OATs respectively, and the yield pick-up of USTS vs. 10y JGBS has eroded to roughly 20bp.

Unless investors are willing to move further out on the credit spectrum — leaving USD corporate and agency debt a potential greater beneficiary of inflows on a relative basis— investors may be more incentivized to seek higher yields elsewhere, especially given incrementally less volatility. Meanwhile, for the Japanese investor, European sovereigns offer a far more attractive yield pick-up. Similarly, while the compression in yield pick-up has been much more modest for sterling investors, OATs and Bunds offer a much higher vol-adjusted return. While the chart above shows that unhedged yield differentials have actually remained wide in spite of the global rate sell-off, the significant weakening in external currencies may lead investors to refrain from adding UST positions, according to Goldman. Of course, to the extent investors feel comfortable taking currency risks (i.e., buying unhedged TSYs) and still need to maintain long duration exposure, this could attenuate the extent of any UST outflows.

Shifting away from private investors, for the foreign official sector, a resumption of Dollar strength should reduce intervention-related flows. More structurally, Goldman’s FX strategists have been highlighting that a number of countries have already been taking steps towards diversifying their reserve holdings, and they see recent geopolitical events raising the probability of official de-Dollarization efforts. On the other hand, the absence of a real alternative to the Dollar for capital market depth – at least for now – and global integration could mean efforts are ultimately quite gradual and measured. Further, the presence of the FIMA facility should, in periods of stress, reduce the risk of forced UST sales if institutions are looking to source Dollar funding.

Taking all this together, is Goldman “concerned” about an abrupt loss in foreign support for Treasuries driving a further sharp repricing of yields? Well yes, but since the bank can’t admit that without blowing up it bullish case for stocks (after all a surge in yields would crater risk assets), instead the bank writes that while it is penciling in a large drop in foreign private (and to a lesser extent foreign official) demand versus last year, it is not yet convinced that this will be a strong catalyst for a few reasons.

For one, Goldman has been arguing that UST supply is also heading lower on account of a declining deficit trajectory (good luck with that in a time when the “green deal” will require $5 trillion in annual capital spending), and there are other investors who may be willing to buy in place of foreigners (such as commercial banks and LDI accounts, although here too don’t hold your breath). More ominously, even Goldman admits that to the extent price sensitive buyers are more reluctant to absorb supply, yields will have to rise further.

Second, non-US supply constraints may limit the set of available investment alternatives investors can rotate into in the near term. To be sure, Goldman believes the trough in net European bond supply is behind us and

However, free float in these markets is quite low by historical standards and it will take time for it to rebuild from very low levels and for the scarcity premium on bunds to dissipate. For this reason, flows may lag the shifting economic rationale we have highlighted until supply accumulates. This is especially true in Germany, where the timing of new supply is somewhat uncertain as the Treasury still has a significant cash buffer that may limit the amount of near-term financing raised via public issuance and the DMO has made no modifications to its 2022 issuance plans as of yet.

Perhaps the biggest wild card is how investors respond to the end of the ECB’s NIRP – here Goldman’s models imply the spillover impact of NIRP has been incorporated in the recent sell-off. Over time, a larger impulse to US yields would require a further upshift in EUR and JPY yield ranges. While this could come through a resolution of the Russia/Ukraine war or a more decisive shift by the BoJ away from YCC — not even Goldman expects either of these to take place for a long time.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 04/21/2022 – 17:20

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com