How Bidenflation Was Made

Via Political Calculations blog,

In late 2020, the policy makers of the Biden administration and its partisan supporters started crafting a new COVID stimulus package. What they wrought set off a chain of events that ultimately led to the cost of living and banking system crisis we face today.

It didn’t have to be that way. When they started their discussions, the participants had modest goals for what an additional stimulus would look like. Considering the federal government had just enacted its fourth Covid relief package on 27 December 2020, totaling $900 billion, no one at the time was advising the Biden administration to pursue for another stimulus of similar size, much less one that was $1 trillion larger.

That changed quickly after 5 January 2021, when President Biden’s political party gained control of the U.S. Senate after runoff elections in Georgia came out in their favor.

With control of the U.S. Congress in hand, the most rabidly partisan among President Biden’s supporters quickly switched gears to exercise their new political power. Instead of linking the magnitude of any new stimulus package to the actual scale of the problem the U.S. economy was facing at the time, they decided they would “go big”, putting their fringe political agenda ahead of sound fiscal policy.

But in ditching sound fiscal policy, they opened a rift among those who had been crafting the new stimulus measure. That rift took the form of an academic controversy that erupted while they were developing what would ultimately become the American Rescue Plan Act, which the Biden administration rammed through Congress and signed into law on 11 March 2021.

The controversy involved an economic concept known as potential output, or potential GDP. Here’s a quick primer:

Potential output is an estimate of what an economy could feasibly produce when it fully employs its available economic resources. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates potential output by estimating potential GDP, which it describes as “the economy’s maximum sustainable output.” The word “sustainable” is important — it doesn’t mean that the entire working-age population is working 18 hours per day or that factories are operating 24/7. Rather, it means that economic resources are fully employed — at normal levels. Potential output (estimated as real potential GDP) serves as an important benchmark level against which actual output (measured as real GDP) can be compared with at any given time.

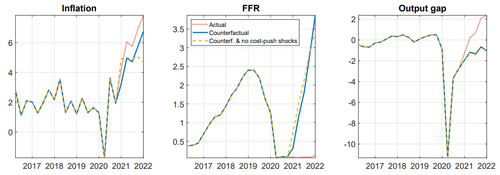

The difference between the economy’s potential output and its actual output is called the output gap, which economic policy makers must consider when shaping major fiscal policies. If they adopt policies that undershoot the gap, they will fail to obtain the full positive results they seek at the cost of greatly adding to the nation’s debt. If they overshoot the gap, they risk creating adverse economic conditions, like inflation, that can fully undermine whatever positive results they hoped to achieve.

These scenarios were known risks at the time the Biden administration was pushing the American Rescue Plan Act forward. In fact, because the stimulus package they were considering had swelled to $1.9 trillion, the risk of creating inflation became a primary concern among the more fiscally responsible members of Biden’s policy making team. But they lost the internal argument when President Biden sided with the most extreme elements among his supporters.

That victory didn’t make the likelihood the enormous new stimulus package would almost certainly overshoot the output gap and create persistent inflation go away. By Inauguration Day, the progressive activists who hijacked the stimulus development still needed to dispell that risk to ensure they could get the massive stimulus through a still closely-divided Congress. Their chosen path to achieve their political agenda would hinge on an assumption cooked up by the Biden administration’s most rabidly partisan supporters: that the nation’s potential GDP and output gap were much larger than the CBO estimated and thus, would not create inflation. That assumption would become the focal point of the controversy for how the stimulus bill could negatively impact the economy.

On 3 February 2021, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget discussed how the assumptions of the size of potential GDP and the output gap being put forward affected the forecasts of how much the stimulus could overshoot the output gap:

The output gap could differ from CBO’s projections. Many forecasts and experts suggest the economy will grow faster this year than CBO estimates. A one percentage point increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth would reduce the output gap to less than $200 billion, in which case the American Rescue Plan would be large enough to close eight to ten times the output gap based on the Edelberg and Sheiner numbers. On the other hand, many have argued that CBO is underestimating full employment and potential GDP. If potential GDP were 1 percent larger than CBO’s estimate, the output gap would total $1.3 trillion through 2023 and the America Rescue Plan would close 115 to 145 percent of the output gap.

The “Edelberg and Sheiner numbers” refer to a 28 January 2021 analysis of the Biden administration’s proposed stimulus produced by the nonpartisan Brookings Institute’s Wendy Edelberg and Louise Sheiner. Just a few weeks later, Sheiner would join with Brookings’ Tyler Powell and David Wessel to report on the controversy related to potential GDP that had erupted among those who were giving input to the Biden Administration’s first major economic policy initiative:

As President Biden and Congress negotiate the next fiscal stimulus package to aid the COVID-19 economic recovery, they will implicitly be making assumptions about the output gap. Analysis by one of us (Louise Sheiner) and our Brookings colleague Wendy Edelberg suggests that Biden’s $1.9 trillion package would result in GDP reaching its pre-pandemic path by the end of 2021 and exceeding it in 2022. In other words, some of the economic activity lost during the pandemic would be made up after the virus subsides.

Based on the CBO’s recent estimate of potential GDP, though, this would leave a large positive output gap—peaking at 2.6 percent in the first quarter of 2022. Some critics — including former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers — argue that pushing output this far above potential could drive up inflation.

Others, including Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, warn against putting too much emphasis on a projected output gap in determining the riskiness of a large fiscal stimulus. They note the significant uncertainty that surrounds any estimate of potential GDP. Indeed, by CBO’s estimates, the U.S. economy was operating above potential in 2019, yet inflation remained subdued and below the Fed’s 2 percent target. Moreover, there is little historical precedent to predict how the pandemic will affect potential output or consumer and business demand once the virus recedes.

With hindsight being 20/20, we know that Larry Summers’ view was correct. President Biden’s COVID stimulus overshot the output gap and created significant inflation, which quickly became evident after its enactment. Mainstream economists using different methodologies indicate the American Recovery Plan Act played a “sizable role” in causing inflation, adding anywhere from 2.6% to 3.5% on top of the inflation rate that would have been recorded without President Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus.

That inflation was allowed to fester for a full year because of a commitment the Federal Reserve made to hold rates near zero percent for as long as possible. It took Americans seeing prices inflate faster than their incomes to finally force the Fed to address the inflation they allowed to gain traction with a series of interest rate hikes beginning in March 2022. Flashing forward one year later, the actions to fix the inflation unleashed by the stimulus measure has had negative impacts on large sectors of the U.S. economy, such as the housing market, and directly contributed to the bank failures that became front page news during the last few weeks.

The Biden administration cannot say they were not warned. Here’s the prescient commentary from Larry Summers’ 4 February 2021 op-ed in the Washington Post:

… while there are enormous uncertainties, there is a chance that macroeconomic stimulus on a scale closer to World War II levels than normal recession levels will set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation, with consequences for the value of the dollar and financial stability. This will be manageable if monetary and fiscal policy can be rapidly adjusted to address the problem. But given the commitments the Fed has made, administration officials’ dismissal of even the possibility of inflation, and the difficulties in mobilizing congressional support for tax increases or spending cuts, there is the risk of inflation expectations rising sharply. Stimulus measures of the magnitude contemplated are steps into the unknown.

In another op-ed just two months later, Summers provided the epitaph for the inflationary failure of the Biden administration’s first major economic initiative with just a simple, understated clause:

Excessive stimulus driven by political considerations was a consequential policy error…

The Biden administration and its extremist political supporters chose to purposefully overshoot the output gap and pretend it would not create the adverse economic conditions that are undermining whatever positive results they hoped to achieve with their $1.9 trillion stimulus. Today, they’re expending much effort trying to avoid accountability for their roles in causing the catastrophic consequences of what is becoming the biggest policy error in generations.

Then again, if they weren’t honest about it from the beginning, why would they start being honest and take responsibility for their failings now?

References

Martin Wolf. Interview with Larry Summers: ‘I’m concerned that what is being done is substantially excessive’. Financial Times. [Online Article]. 11 April 2021. Here’s a video of the full interview:

François de Soyres, Ana Maria Santacreu, and Henry Young. Demand-Supply Imbalance during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Fiscal Policy. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review. First Quarter 2023, 105(1), pp. 21-50. [PDF Document]. DOI: 10.20955/r.105.21-50. 20 January 2023.

Francesco Bianchi and Leonardo Melosi. Inflation as a Fiscal Limit. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper No. 2022-37. [Online Article]. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.4205158. 21 September 2022.

Doreen Fagan. Understanding Potential GDP and the Output Gap. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Open Vault Blog. [Online Article]. 4 August 2021.

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. How Much Would the American Rescue Plan Act Overshoot the Output Gap. [Online Article]. 3 February 2021.

Wendy Edelberg and Louise Sheiner. The macroeconomic implications of Biden’s $1.9 trillion fiscal package. Brookings Institute Up Front. [Online Article]. 28 January 2021.

Tyler Powell, Louise Sheiner, and David Wessel. What is potential GDP, and why is it so controversial right now? Brookings Institute Up Front. [Online Article]. 22 February 2021.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 03/30/2023 – 14:40

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com