China’s 300% Debt And Dilemmas

By Teeuwe Mevissen, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

Summary

- China’s combined debt (Government, corporate and household) is more than 300% of GDP

- China’s local government debt has been rising sharply for years and is seen as a key risk among investors in Asia.

- With declining income from land sales and increasing expenditures to service these high levels of debt, financial risks for local governments are increasing.

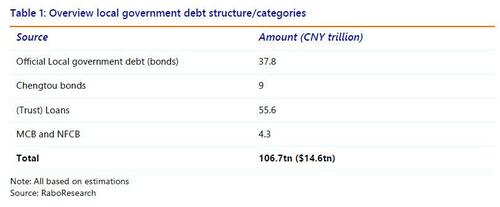

- Local government finance vehicles add to high levels of debt. We estimate that total local government debt is CNY 106.7 tn or USD 14.6 tn.

- Some local governments are scaling down government services and salaries of workers

- High levels of local government debt is likely to put a drain on economic growth for some time to come.

Introduction

Local governments have been a pillar of China’s economic growth model for decades. Land-sales for (commercial) real estate projects, infrastructure investments of all sorts and controlling the allocation of credit to State Owned Enterprises (SOE) have significantly contributed to economic growth. But recently, more and more investors and analysts alike worry about the sustainability of the high levels of local government debt. While the problems in the real estate sector have received much attention in the past two years, the high levels of local government debt have been somewhat overlooked, even as they are currently considered a key risk for economic growth and financial stability for 2023 and beyond. Indeed, the problems in the real estate sector are part and parcel of the problem that local governments are facing right now, but clearly there is a lot more to it. With local governments being responsible for the vast majority of total tax expenditures (estimated at almost 88% in 2023), this creates potential challenges for maintaining robust economic growth. Moreover, holders of local government bonds or bonds issued by local government finance vehicles (LGFV) might run significant credit risks.

This paper will specifically try to assess the financial situation of China’s local governments and tries to answer the question whether and to what extent the levels of local government debts are indeed alarming. We make an estimate of China’s total local government debt by comparing official data of local government debt (where available) with all outstanding local government bonds. We analyse over 11.000 securities to determine local debt to GDP for the relevant administrative levels and determine weighted average maturities and weighted average yields for the respective administrative levels. We also include all outstanding so called Chengtou bonds, i.e. urban construction development bonds. The next step is to look at corporate bonds which also include so called Municipal Corporate Bonds (MCB). We finalise our analysis by looking at balances from the financial sector (excluding the shadow banking sector) to estimate the amount of ‘hidden debt’. We conclude that for some regions there is cause for concern. At best, mitigating measures to deal with the high amount of debt is likely to weigh on China’s future growth potential.

China’s overall debt situation

China’s miraculous path of economic growth and development has received praise all over the world. Never in history was a country so successful in pulling hundreds of millions of people out of levels of absolute poverty. Clearly this could not have been realized without huge amounts of foreign and domestic investments. In other words, money was needed and lots of it. Money that also needed to be borrowed.

While borrowing money makes a lot of sense when the rate of return exceeds the costs including the costs of servicing this debt, this obviously is not always the case. In the case of China, some of the money that has been borrowed has ended up to be speculative borrowing. This includes the real estate sector, households (mainly real estate), poor investment projects by corporates and overambitious local governments that felt the need to simply make good on their economic growth targets by investing in real estate- and infrastructure projects.

Of course investing inevitably comes with risks attached and therefore some losses will have to be incurred. However, at certain levels of debt, the level itself can become a problem regardless of the quality of the loans that have been provided. Liquidity problems, for instance, can occur despite a high quality asset portfolio. Regardless, with a total level of debt of more than 300% of GDP it is clear that China’s fast rising levels of debt need to be brought under control. As can be seen from the graph below, in less than 20-years total debt-to-GDP more than doubled. Moreover, the metric shown in figure 1 is considerably lower both in the US and the Eurozone that -according to the BIS definition – have debt levels of respectively 265% and 255% of GDP

Local Government debt levels

No one knows the weight of another one’s burden

In April this year the total level of government debt was estimated at around USD 23 trillion or CNY 152tn. From this estimate, around 60% (CNY 91.7tn) is assigned as implicit government debt, i.e debt that doesn’t count as ‘official’ government debt. The absence of official data on borrowing by local governments via non-marketable assets has led to a broad range of estimates of what the total size of outstanding implicit debt issued by LGFVs could be.

According to the estimate above, CNY 60tn, or USD 9tn is to be assigned to LGFVs. An estimate by the Wall Street Journal amounts to USD 7tn, while the IMF estimated total LGFV debt at 50% of China’s GDP, which would also amount to approximately USD 9 tn. Wind estimated the total amount of outstanding LGFV debt at almost USD8tn at the end of 2021. The uncertainties that surround these estimates of the amount of implicit government debt plague both onshore and offshore bond markets for LGFV’s. These uncertainties also have received attention from China’s top leadership and recently it became known that China has started a nationwide effort to reveal the amount of hidden debt.

Doing the math: estimates, caveats and assumptions

Of course some of these differences between the estimates can be attributed to changes in the exchange rate, date of measurement or methodology. However, as we have flagged several times, China analysts often need to come up with proxies and estimates since fewer and fewer data is being published. So with this warning, we will explain our methodology, assumptions and estimates below.

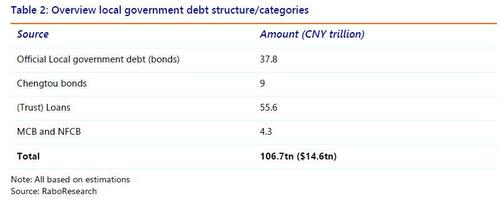

In order to estimate the total amount of local government debt we will add up:

- the total amount of local government bonds outstanding,

- the amount of Chengtou bonds outstanding,

- an estimate of outstanding MCB’s, and

- our proxy for non-marketable local government loans (via financial sector)

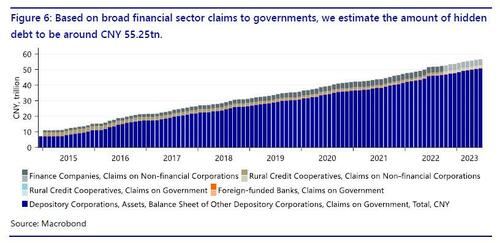

To estimate the latter, we look at banking balances of depository corporations, foreign funded banks, rural credit cooperatives, and finance companies. We then select their claims on governments and claims to non-financial corporations.

While we are aware of the fact that not all non-financial corporations are state-owned, the total amount is relatively small compared to the claims on governments (figure 5 below). Furthermore, we also acknowledge that there are more ways in which local governments can finance themselves so that simply looking at the financial sector’s claims on governments likely underestimates total non-marketable local government debt. Furthermore, we assume that all claims on government are claims on local governments and that the central government doesn’t fund itself via non-marketable loans. In the following four sections we will simply provide the outcomes of our analyses. For those interested in our methodology we refer to the appendix at the end of this publication.

Local government bonds

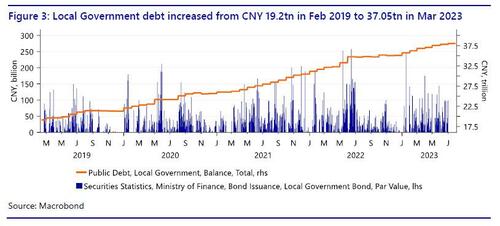

Official local government debt is measured by simply adding up all outstanding amounts of bonds issued directly by local governments. This debt adds up to CNY 37.05tn on March 2023.

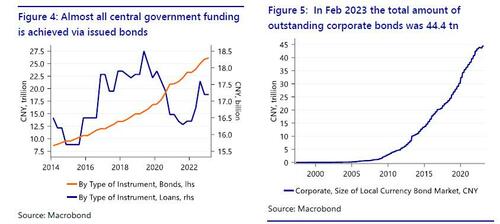

As we already mentioned above and as figure 4 shows, only CNY 17bn of central government debt is in the form of loans. Since this amount is negligible in comparison to the total we will not correct for this amount when analyzing loans to local governments. Figure 5 shows total outstanding corporate debt of which we assume that SOE’s account for 75% of outstanding corporate bonds. We further assume that 40% of these bonds can be assigned to LGFV.

Finally, figure 6 provides an overview of the financial sector’s claims on government excluding the shadow banking system which generally owns bonds which we exclude to avoid double counting since the bonds that they own are already included in our analyses. As with corporate bonds, we assume that 75% of financial claims on NFC can be assigned to SOE’s of which 40% can be assigned to LGFV. This adds up to CNY 55.6tn. When we add up all 4 separate categories the total amount of local government debt amounts to CNY 106.7tn or $14.6tn (based on a USD/CNH exchange rate of 7.3.

A double-edged budgetary sword

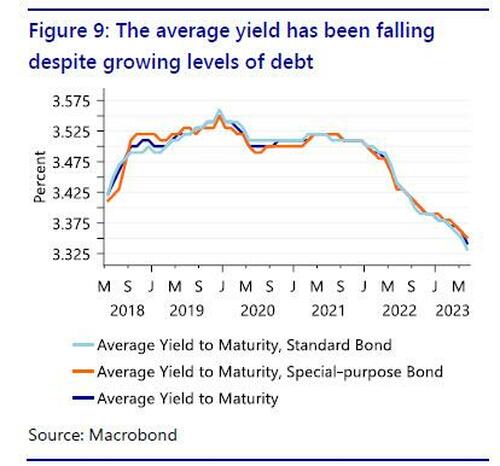

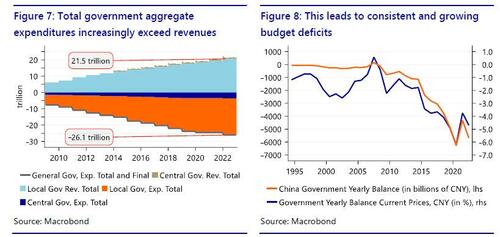

But for some local governments problems seem to go further than fast growing levels of debt. Local governments have consistently run budget deficits for years as can be seen from figure 7 and 8 below. With debt levels growing, so has the share of local government budgets that needs to be spent on interest payments on those debts. Moreover, with declining revenues from land sales as a result of the real estate crisis, local government budgets have become even more strained. While funding has generally become cheaper (see figure 9) it remains to be seen whether this trend will hold. Should market participants start to question the credit worthiness of local governments, this trend could quickly reverse.

Additionally, it is important to bear in mind that these lower levels of average yields have to be paid on a much larger amount of nominal debt. To be more specific, while in 2020 yields for standard bonds averaged around 3.50% and in 2023 approximately 3.35%, the total amount of outstanding debt went up from CNY 24tn to CNY 37tn.

This means that in 2020 total interest to be paid on outstanding standard government bonds amounted to CNY 840bn while in 2023 this would already be CNY 1,240bn. To summarize – total (interest rate) expenditures have gone up while (potential) revenues have gone down, creating a double-edged budgetary sword.

In some cases we now see that this leads to challenges for some local governments to continue to provide the usual level of government services. This could mean the delay of the salary payments for (local)government workers, lower pension benefits or downscaling of healthcare services. But local governments are also urging local companies to repay their (overdue) debts. More extreme incidents have also been reported, such as fining a restaurateur for $700 for serving a cucumber dish. For obvious reasons we assume that the more indebted regional governments run the highest risk of needing to cut expenditures or worse default.

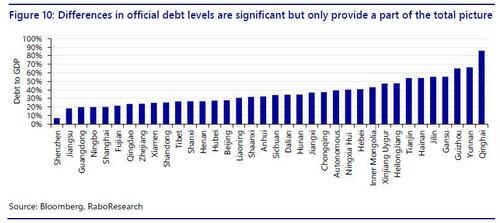

Figure 10 shows the ratio of debt to GDP for local governments. It is important to consider that China distinguishes different levels of local government. While the constitution identifies three levels of government, in practice there are five. Here, we mainly focus at the provincial level which includes provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities and special administrative regions. Furthermore we have included a few prefecture level cities that have issued their own bonds, such as Beijing and Shanghai.

From the graph above it becomes clear that official local government debt to local GDP ratios differ wildly, from less than 10% in Shenzhen to almost 90% in Qinghai. Furthermore, if we look at the financially more vulnerable regions in 2020, we see that in 2023 not much has changed. Qinghai, Yunnan and Guizhou are still the most vulnerable regions with debt to fiscal revenue reaching 1087% in Yunnan in 2022 meaning that it would require almost 11 years of revenues to pay off Yunnan’s local government debt. Most vulnerable regions are located in the North- and South-West of China, while China’s economically vibrant East coast are generally characterized by significantly healthier debt ratio’s. As such, these regions look a lot more able to raise tax revenues. They also have more valuable assets to sell if that would ever be needed.

It is important to realize that according to the local government debt risk emergency response plan article 4.1 ‘Local governments are responsible for repaying debts they borrow, and the central government implements the principle of no bailout’. In general, the debt emergency response is dependent on the severity of the specific debt risk event but we will not elaborate much further on the legal technicalities here. The key point is that a central government bailout of a local government that risks falling into default, is anything but certain.

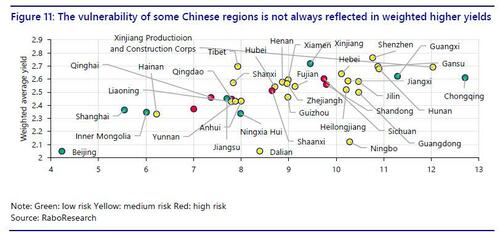

When we zoom in further on the amount of outstanding official local government debt, we see that, whilst there is a positive relationship between the average maturities and yields, the relative financial vulnerability of a region or province is not necessarily reflected in weighted average yields. An important reason for this is the assumption by investors that official local government debt has an implicit guarantee from the central government. But as we have concluded above, it remains to be seen whether and, if so, to what extent, the central government will bail out local governments.

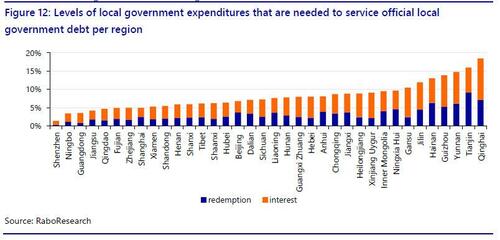

Having calculated the weighted average yield we can also obtain an estimate of the amount of interest that is needed to service these outstanding official local government debts. Since we also know the total level of local government expenditures – which amounts to CNY 23.67tn – we can obtain the average percentage of debt servicing expenditures compared to total expenditures.

Our calculations show that almost exactly 4% of total official local government expenditures is spent on interest of outstanding official local government debt. Needless to say that there are significant differences between regions. Since we do not have data about individual local government budgets we calculate our estimation of debt servicing costs per region by assuming that local government budgets are divided equally based on the weight that a certain region has in total GDP. This gives us the following estimates.

While it is clear that the assumptions that we made only lead to an approximation of the true financial situation for local governments, the most fragile local governments are the usual suspects. In a previous publication that investigated the link between higher rates and government finances we assumed that if a (local) government has to spend more than 10% of the total expenditure budget to service existing levels of debt, this starts to put (local) government finances under pressure. We apply this threshold on our analyses as well. As can be observed from our estimates this includes 7 of the 36 regions. Based on an average level of debt servicing of 7.2% which is the average level of bonds rated BB by Fitch, 19 regions would face financial challenges. However it is important to realize that we included redemptions for the whole of 2024. This means that if we had used a 12 month window the outcomes would be slightly lower.

Recent developments

Looking at the most recent developments, China appears to have decided to double down on the same path that we have become so accustomed to; i.e. let local governments borrow more money to spend more on infrastructure. Indeed, as recently as 31 August it became clear that local governments are accelerating the pace of borrowing (which is not visible in figure 3 above since these are the special bonds/Chengtou bonds discussed previously). Local governments are accelerating issuance to meet their 2023 targets and are expected to raise the remainder of the 2023 target of CNY 3.8tn before the end of this month according to minister of finance Liu Kun. This would mean that local governments still have to issue approximately CNY 800bn to meet this target.

Furthermore, local governments that have not used their quota in previous years are allowed to issuance additional bonds. It is estimated that this could free up an additional amount of CNY 1tn which would then be used for debt swaps, i.e. issuing a bond to pay of bank loans or other forms of non-standard/non marketable loans. However, as we have discussed in previous publications, new infrastructure projects increasingly provide diminishing marginal returns on investments made. Additionally, while refinancing can put further pressure on average yields (figure 8), the total amount of debt is likely to increase by another 1.8tn regardless.

So what is next?

Now that we have obtained an overview of the ins and outs of China’s local government debt situation it is time to reflect on what this means for China’s economy. First, we conclude that -based on our benchmark assumption that a (local) government that spends more than 10% of the total budget on debt servicing is financially fragile – a significant share of China’s local governments have or are approaching risky levels of debt.

If the current trend of increasing debt levels continues, we believe it is a matter of time before a significant share of local governments will run into financial difficulties. At this moment it is mainly the fragile liquidity position that local governments are struggling with. While the PBOC can provide for extra liquidity in the financial system by lowering the 7-day RRR for example, it should be clear that this will not offer a structural solution.

Although higher taxes would increase local government revenues, it could also put further downward pressure on consumer demand. Currently, total consumption is already at low levels contributing only 38% to total GDP growth. If Beijing would be serious about reforming their economic model from a purely export-based economy to an economy of dual circulation – i.e. remaining open for trade and investments (external circulation) while prioritizing domestic demand (internal circulation) – raising taxes is not a policy that would help achieving that goal. Remember that China also postponed the imposition of a real estate tax in order not to aggravate the real estate crisis. Increased revenues from land sales are also not to be expected in the foreseeable future. So, with limited possibilities to raise local government revenues we are left with a number of other options. In no particular order, these options are:

- cut local government spending

- blend and extend operations of the current outstanding debt

- a bail-out of highly indebted local governments by the central government

- defaulting on debt by local governments

To date, no bond defaults have yet occurred, but local governments have already defaulted on nonstandard debt in several cases. As long as there is no risk to the broader financial system we do not expect that Beijing will come to the rescue when a local government would not be able to service its debt obligations anymore.

While some local governments have reigned in spending as we discussed above, they are also pressed to issue more debt and prop up spending. So cutting local government spending does not seem to be Beijing’s preferred strategy. Indeed, we think that blend and extend operations will turn out to be the preferred and most likely policy.

In this case, major state banks will be asked to be lenient towards local governments and the PBOC will support those state banks. This could be done by adjusting interest rate policies and/or lowering the required reserve ratio – currently at 7.6% for relevant banks (not all banks have the same RRR as this depends on the size of the balance sheet). Indeed we do see an high chance of the PBOC lowering the RRR this month.

No crisis, but weighing on growth all the same

In other words, those who are waiting for a big bazooka will likely be disappointed. However, we also do not expect an uncontrolled crisis that would put the financial system as a whole in danger. First of all because it can simply be avoided. China still has considerable amounts of foreign reserves and also has the means to increase tax revenue if necessary. Although this would go at the cost of domestic consumption. Additionally, an uncontrolled collapse would come with socioeconomic instability which is something that Beijing wants to prohibit at all costs.

In the end the current local government debt situation is an example of “choose your poison”. Losses are likely to be divided between bond holders and banks. While the amount of offshore bonds is limited, the holders of those bonds are likely to be the first ones to get hit with a haircut as we have seen in the real estate sector already. So in the end we expect a combination of different measures. The tool of preference is likely to be blend and extent operations. Still, a blend and extent approach would mean that the fragile financial position of local governments will continue to weigh on economic growth for a long time to come.

We also expect some defaults to occur and here the hybrid bonds, which invest in multiple (commercial) projects, seem to be the most risky bonds given the fact that the government is less likely to save SOE’s. Indeed the bonds that are most likely to be eligible for a bail out are bonds that are officially regarded as local government debt. Regardless, China’s economy is likely to be at the start of a long process of deleveraging that will suppress economic growth for years to come.

Appendix

Methodology

Official local government debt (issued bonds)

Starting with the official total amount of debt for local governments we see that this stood at CNY 37.05tn (USD 5.17tn) in March this year. Again, this figure excludes so-called Chengtou bonds and non-standard/non-marketable products which are generally bank loans or private placements to local governments made by (local) banks.

When looking at the development of this narrow definition of outstanding local government debt we still see that the absolute level of debt has almost doubled over the last four years. While it is understandable that government debt has risen given the huge health care costs and the government stimulus that had to be provided during the Covid Pandemic, the current pace of increasing levels of debt is unlikely to be sustainable in the future.

Chengtou Bonds

When including Chengtou bonds, which unlike ‘normal’ local government bonds are often issued for specific urban construction development purposes, we obtain a more accurate picture of local government’s total amount of outstanding debt. Chengtou bonds can be separated in two different classes: quintessential and hybrid bonds. In both cases the ownership is in the hands of local government entities, but hybrid bonds hold more diversified assets and as such are more similar to SOEs. This means that a hybrid bond can invest in both public as well as in private projects.

The idea of issuing hybrid bonds was initially stimulated by the central government to raise revenues in order to decrease reliance on local government finances. However this also led to excessive risk taking. Furthermore, from the central governments point of view, hybrids are deemed less important than the quintessential bonds that solely finance collective projects. This heightens the credit risk on hybrid bonds. Until recently, there was a tendency to attract more capital from abroad via offshore Chengtou bonds, but the Fed rate hiking cycle has made this form of funding increasingly less interesting.

Bloomberg data suggest that at the moment of writing there are 11,517 outstanding onshore securities which amount to CNY 8,818bn. When we include offshore bonds this amounts to 12,047 securities, adding up to CNY 8,887bn. Together with the amount of official outstanding government debt this totals approximately CNY 46tn of debt or about USD6.5tn. This still falls way short of the estimates by other institutions.

Municipal Corporate Bonds (MCB)

This is largely because we have not included non-standard/non-marketable government debt and MCB. We will first outline our assumptions behind our estimation of the more hidden part of local government debt. First, when we look at how the central government funds itself, we see that the vast majority of central government’s cash intake comes from issuing bonds.

In figure 4 one can observe that, indeed, only a bit more than CNY 17bn is funded through (bank) loans. We therefore assume, for simplicity, that all net claims on government are bank loans to local governments. We also include all claims on non-financial corporations since many SOEs are qualified as non-financial corporations. Indeed the bonds that are issued via LGFV’s are also known as MCB’s.

While these bonds are initially traded via the interbank market, the majority are held by wealth managers and the shadow banking system. We exclude the shadow banking sector since we have already included all bonds that have been issued by local governments (see figure 3) and we are not focusing on credit exposure in this special. Moreover, we have no means to analyse this sector because (reliable) data is absent. Finally we also exclude debt secured by stocks given that it is not considered government debt for domestic creditors according to article 3.3.3 subsection 1 which says: … “Stock secured debt is not government debt. According to the Guarantee Law of the People’s Republic of China and its judicial interpretations, except for loans from foreign governments and international economic organizations, the guarantee contracts issued by local governments and their departments are invalid, and the local government and its departments shall not bear the liability for debt repayment”…

This leaves us with estimating which share of corporate bonds should be considered as local government debt. Many estimate that as much as 40%-50% of outstanding corporate bonds are related to local government debt. The total amount of outstanding corporate bonds in China is about CNY 60tn (based on Bloomberg data). However these outstanding corporate bonds also include many Chinese banks. The Asian Development Bank reports an outstanding amount of local currency bonds for the corporate sector at CNY 44.4tn so we use this amount for our analysis. According to a IMF paper from 2019, SOE’s account for 75% of non-financial corporate debt. This would imply that 75% of CNY 44.4tn is in scope. Staying on the conservative side, and in line with other approximations, we estimate that 40% of this debt is related to LGFV’s. This amounts to CNY 13.3tn of outstanding local government debt. However we have to subtract the outstanding amount of Chengtou bonds since these are incorporated in the total amount of outstanding corporate bonds. This leaves us with CNY 4.3tn of additional outstanding debt.

Non-marketable debt (loans by financial sector)

We can now come up with our estimate/proxy of the banking sector’s exposure to local government debt. In figure 5 it can be seen that depository corporations by far hold most claims on government. The total amount is CNY 51.1tn. We keep the claims on NFC constant since data is only available until 2022. Similar to the assumption that we made earlier, we include 75% of this debt (6tn) as exposure to SOE’s. This amounts to CNY 4.5tn in additional exposure. We estimate that the financial sector’s total exposure to local governments amounts to roughly CNY 55.25tn which is close to USD 7.6tn. This is actually very comparable with other estimates that we referred to above.

If we add this up to the numbers in our previous findings this would amount to a total amount of local government debt of CNY 106.7tn or close to USD 14.6tn. This is higher than the CNY 95tn (or USD 13.2tn) estimate based on an analysis by Goldman Sachs.

Breakdown of China government debt, all 152TN yuan of it. pic.twitter.com/H5C2Jw5U71

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) June 5, 2023

Clearly these changes can be explained by differences in methodology and a different time of measurement. As the graph below shows, the claims that depository corporations have on the government rose from CNY 47.6tn in December 2022 to 51.14tn in July 2023; an increase of almost 7.5%. This already explains almost CNY 4tn difference.

(Also available in pdf format to pro subs here)

Tyler Durden

Sun, 09/24/2023 – 20:50

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com