How The Race For A COVID-19 Vaccine Could Go Horribly Wrong For The Market

Tyler Durden

Tue, 08/04/2020 – 21:05

The research departments at Wall Street investment banks have every incentive to provide clients with a stream of worrisome (but not too worrisome) reports about the future trajectory of the global coronavirus outbreak. After all, too much unpleasant fearmongering, and they might instead go somewhere else, where another broker can tell them exactly what they want to hear. A lot of people are like that

Which is why a research note published by Goldman’s top economist Jan Hatzius, who made his bones with a set of bearish calls just before the financial crisis, is so interesting. With public officials in the US, UK, China, Russia and elsewhere promising that a workable vaccine is just around the corner – Dr. Fauci has reassured Congress on multiple occasions that an FDA-approved vaccine by the end of the year is a realistic timeline – the market appears to be pricing in the best-case scenario. Stocks greet every new headline – even headlines that are simple rehashes of previously released early clinical trial data – with a modest rally.

At the very beginning of Hatzius’s note, he points out that his ‘base case’ calls for a COVID-19 vaccine to be widely available throughout the US and Europe by the end of Q22021, or the end of Q32021, at the very latest. There are more than a hundred vaccine candidates in the making, but all the major candidates are targeting the same protein. This means that once a vaccine succeeds, there should be at least a modest surplus – though, to be sure, governments are striking deals for future vaccine supplies left and right.

This base case, in turn, supports Goldman Sachs’ ‘house view’ for “above-consensus” global growth in 2021 (after all, so much of economics is influenced by perception).

But since most of the vaccine candidates are focused on the same approaches and are working off the same assumptions – that is, everything we currently know, or think we know, about SARS-CoV-2 – there is, of course, a risk that some unforeseen obstacle could disrupt this timeline.

And if that happens, things could go south in a hurry.

Or as Hatzius puts it: “the risks around this vaccine baseline…are clearly skewed…toward the downside…”

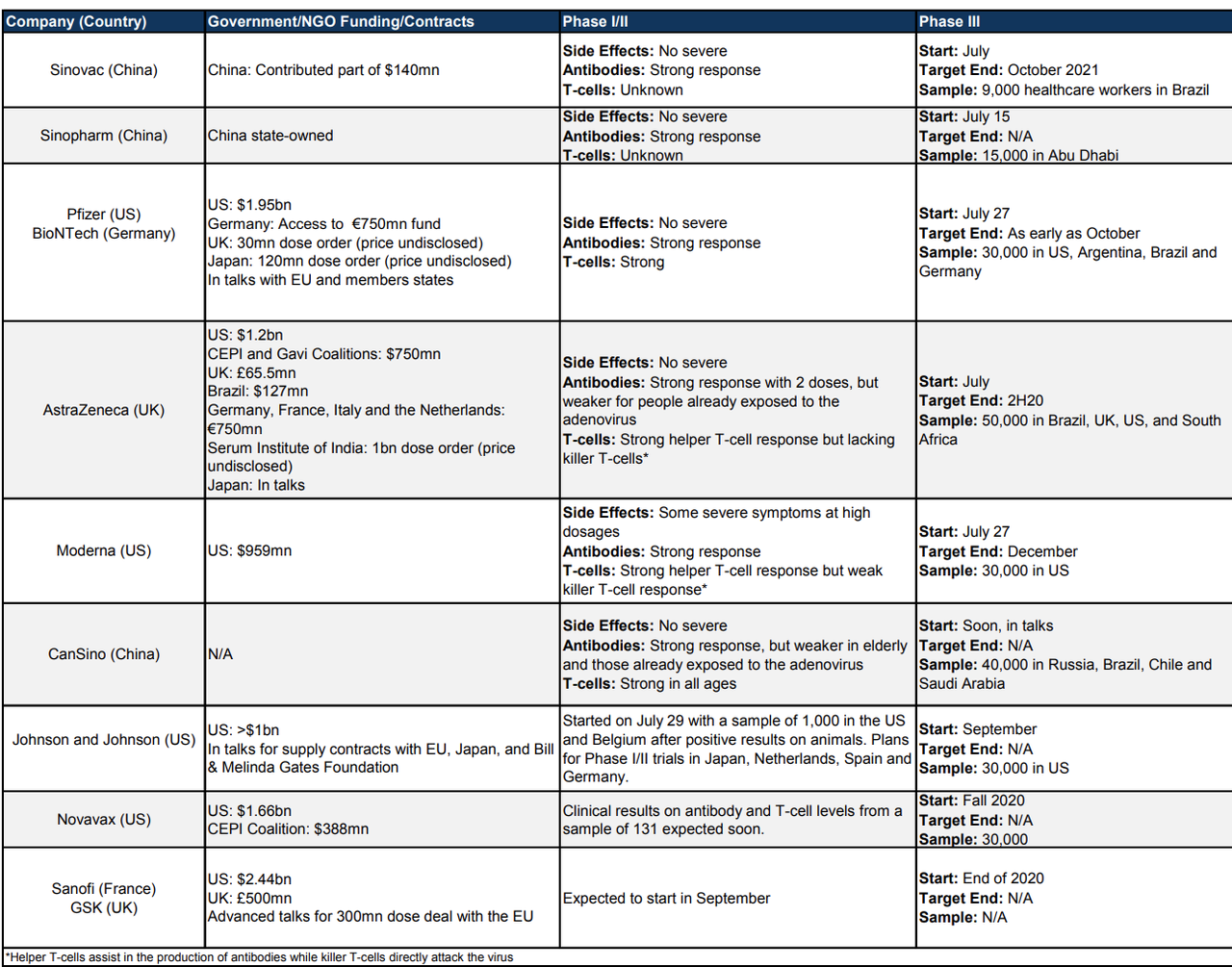

First, Hatzius starts off the note with a helpful summary of where most of what are seen as the biggest and most credible vaccine projects are at.

Then, Hatzius explains Goldman’s research on vaccine approvals. The firm found that the race to discover a vaccine for HIV was perhaps the best comparable example. Since in the beginning, many competitors were working on similar projects. Typically, the more parties are working on vaccine candidates, the more quickly a vaccine is approved by the FDA. But HIV was one interesting example where this wasn’t the case. Note: this isn’t the only time we’ve brought up HIV in our writings on COVID-19.

Since all the big vaccine projects are focusing on one of only a handful of approaches – for example, AstraZeneca/Oxford and Moderna are both focusing on vaccines that rely on messenger RNA (known as mRNA). Others are focusing on antibodies culled from the blood of survivors. Because the number of approaches is so small, the outcomes for these trials are likely highly correlated…

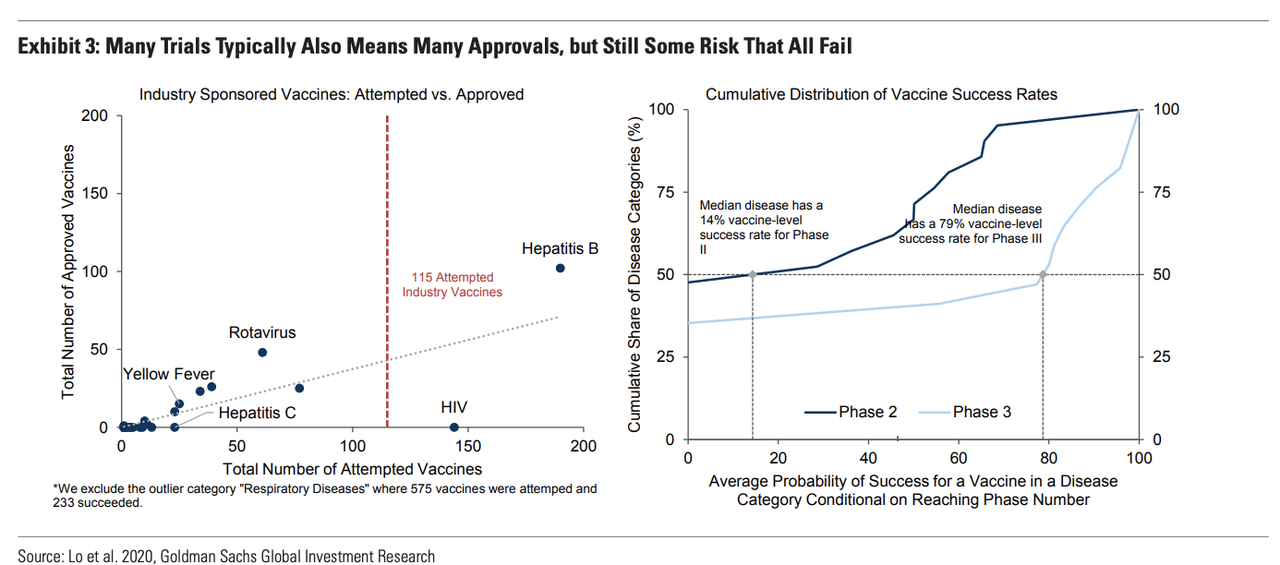

As the left panel of Exhibit 3 shows, a large number of industry sponsored vaccine attempts typically goes hand in hand with many approvals. This historical relationship would suggest an eventual approval of 43 vaccines. Furthermore, six candidates are already in Phase III. The historic approval odds of a given Phase III vaccine targeting the median disease is 79%. However, the history of trials and the fact that all major vaccines currently target the same spike protein also suggest that vaccine approvals are likely correlated, with either many succeeding or all failing, as for HIV.

We tentatively expect FDA approval of at least one vaccine this fall. First, six developers running late-stage trials following solid Phase II results are planning to seek approval in 2020Q4. Second, regulators have ramped up the transparency, flexibility, and speed. The FDA, for instance, has released specific safety and effectiveness standards, works directly with developers, analyzes interim results, and can provide Emergency Use Authorization as soon as studies have demonstrated safety and effectiveness. However, conflicting expert views on the odds of 2020 approval highlight the risk to our baseline timeline (Exhibit 4).

Increasing the risk of an outcome like what we see in the chart below for HIV.

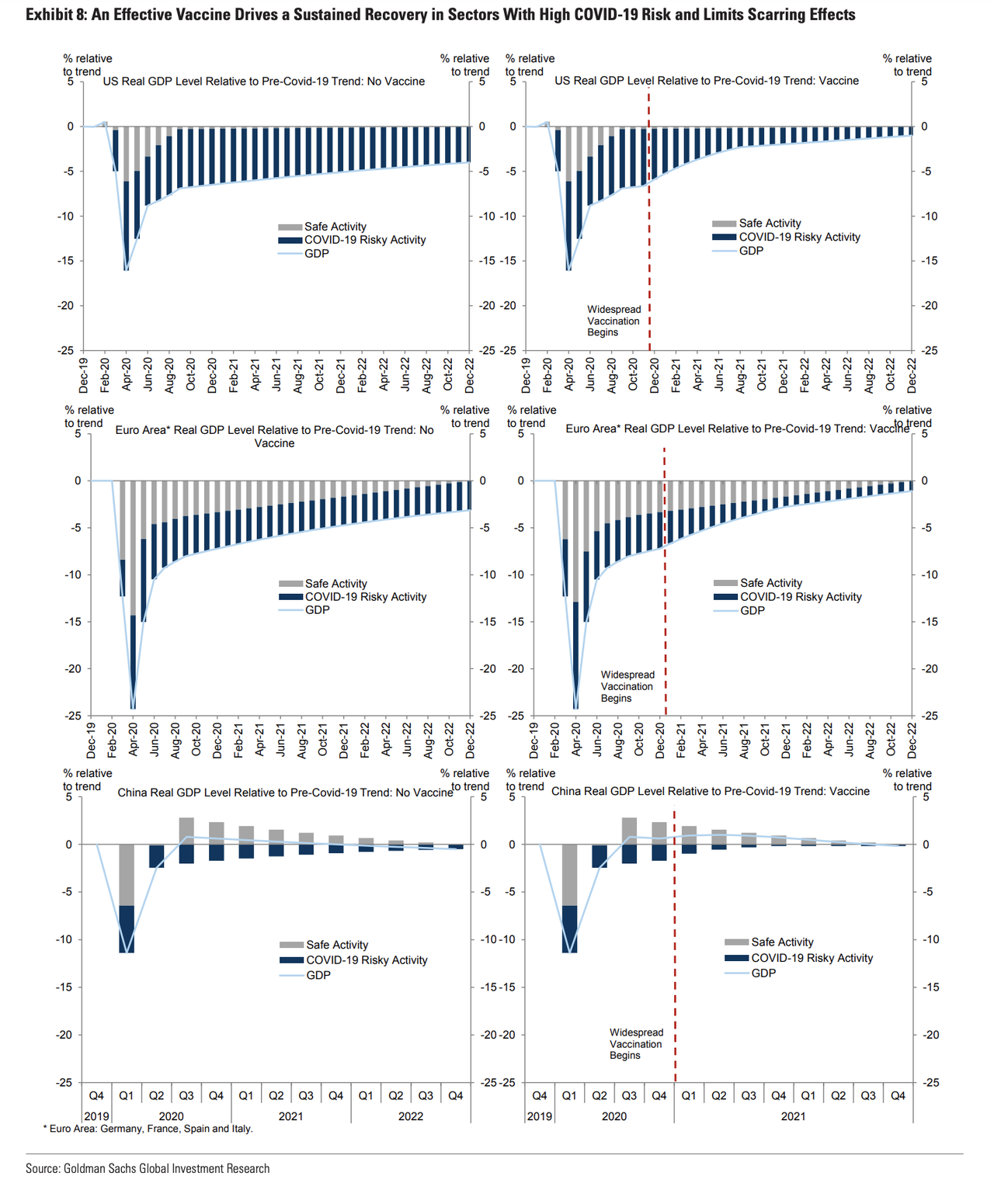

Once a vaccine is discovered, Goldman expects the US, Europe and China will all experience a pronounced economic boost (though Goldman expects the boost to the US to be bigger, since the virus is more widespread).

By that logic, if a vaccine isn’t forthcoming in the next year or two, the US is likely also the furthest along the path to herd immunity, if such immunity is even possible for COVID-19. Some studies appear to show some decay in antibody levels, though it’s impossible to draw any solid conclusions at this point. Virologists insist that infection definitely confers some level of immunity.

On the other hand, it’s also possible that another treatment will lessen the need for vaccines by proving to be a reliable and effective treatment for the disease. Dr. Anthony Fauci is now touting a new class of drugs called manufactured antibodies, as Reuters explained on Tuesday.

These “manufactured” antibodies are grown in bioreactor vats, and essentially replace the antibodies that your body naturally manufactures to fend off infections.

As the world awaits a COVID-19 vaccine, the next big advance in battling the pandemic could come from a class of biotech therapies widely used against cancer and other disorders – antibodies designed specifically to attack this new virus.

Development of monoclonal antibodies to target the virus has been endorsed by leading scientists. Anthony Fauci, the top U.S. infectious diseases expert, called them “almost a sure bet” against COVID-19.

When a virus gets past the body’s initial defenses, a more specific response kicks in, triggering production of cells that target the invader.

These include antibodies that recognize and lock onto a virus, preventing the infection from spreading.

Monoclonal antibodies – grown in bioreactor vats – are copies of these naturally-occurring proteins.

Scientists are still working out the exact role of neutralizing antibodies in recovery from COVID-19, but drugmakers are confident that the right antibodies or a combination can alter the course of the disease that has claimed more than 675,000 lives globally.

“Antibodies can block infectivity. That is a fact,” Regeneron Pharmaceuticals executive Christos Kyratsous told Reuters.

A timely vaccine will help drive a recovery and limit “scarring effects” on the economy, Hatzius said.

Since the race to find a workable vaccine is so intense, many are worried that a rushed job could produce a vaccine that’s ineffective, or worse, harmful. Even if at least one vaccine is approved before the end of the year as Goldman expects (though it admitted it’s still relatively uncertain on this) it’s possible that we could later find its effectiveness limited. Studies have shown COVID-19 antibodies start to decline after a few months. It’s likely that one’s antibody count doesn’t have much bearing on the body’s ability to fend off infection, since the body can always produce more. But it’s also possible that this could be a sign of fading immunity to the disease.

“An early approval does not imply full effectiveness or long-run protection,” Goldman writes.

And even once a vaccine is approved, there’s precedent for the FDA withdrawing its approval – however unlikely that might seem right now.

An early approval does not imply full effectiveness or long-run protection. On effectiveness, the FDA only requires the vaccine to show a difference of 50% between events, such as infection, in the vaccine versus control arms of the study. The effectiveness for the elderly also remains uncertain, with weaker antibody responses to the CanSino vaccine and no elderly testing for most other vaccine trials so far.4 On the length of protection, little reinfection so far and the potential of T-cells to provide long-lasting immunity are encouraging while a recent Nature study found that antibody levels started to decline after 2-3 months.

However, as noted by a recent NY Times Op-Ed by leading Yale immunologists, a waning antibody count does not necessarily indicate waning immunity because memory B cells can produce additional antibodies and lead to long-term immunity. Finally, approval could be overturned subsequently as happened with the yellow fever and rotavirus vaccines that were pulled from the market after rare severe side effects.

Thanks to all the government deals with big pharma, if most of the leading vaccines succeed and achieve their production and purchase targets, the US and the UK will probably have a big surplus, while the EU and Japan – which are currently reportedly in talks with producers – also should have large supplies.

Despite China’s promise to dole out vaccines to the developing world, the lack of their own pipeline makes the outlook for the EM universe less certain.

Now, for an equally important question: is the market under-pricing the risk of some delay in the process of finding a vaccine? As Hatzius explained, the ‘diversity’ of vaccine projects doesn’t confer as much security as some might be inclined to expect.

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com