Back in February 2019, we reported that the San Francisco Fed, already infamous for wasting millions in taxpayer funds on glaringly idiotic research, reached a remarkable, goalseeked conclusion: in a paper titled “How Much Could Negative Rates Have Helped the Recovery“, it found that – as the title suggests – negative interest rate would have helped the recovery.

As a reminder, unlike Europe or Switzerland, where deposit rates have been negative for years, the US central bank is generally perceived as not having a mandate to take rates below the “lower bound” or negative, i.e. to implement what is affectionately known as “NIRP.” And yet, according to the regional west coast Fed this is a mistake, because research from San Fran Fed’s Vasco Curdia, “allowing the federal funds rate to drop below zero may have reduced the depth of the recession and enabled the economy to return more quickly to its full potential. It also may have allowed inflation to rise faster toward the Fed’s 2% target. In other words, negative interest rates may be a useful tool to promote the Fed’s dual mandate.“

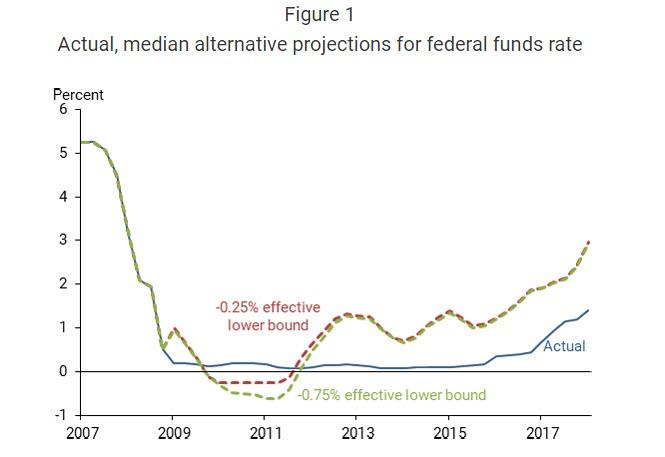

While the report engages in the type of tortured, goalseeked analysis that we have grown to “love” from central banks for the past decade, the same central banks who did not anticipate that their disastrous bubble-blowing policies would result in the financial crisis of 2008 (which last we checked, has not been blamed on Putin just yet), and presents the following chart to confirm that, indeed, if only the Fed had cut rates to -0.75%, the recovery would have magically been far stronger…

… and concludes that NIRP is precisely what the (econ) PhD(octor) should have ordered:

This Letter quantitatively evaluates the beneficial impact a negative Fed policy rate could have had during the recovery from the Great Recession. While it’s difficult to capture all the complexities of the economy in a model, this analysis suggests that negative rates could have mitigated the depth of the recession and sped up the recovery, though they would have had little effect on economic activity beyond 2014. The analysis also shows that the interest rate does not have to fall too deeply into negative territory to accomplish meaningful economic improvements.

As we concluded then “In short, NIRP would have made the recession shorter and less acute according to the San Francisco Fed, and since it is impossible to argue the counterfactual, we now have “research” that sets the framework for what happens next.“

That this report was issued just days after the ECB itself “found” that QE had, hilariously, reduced inequality, was probably not a coincidence.

ECB asset purchases have reduced inequality in the eurozone, our research shows. They have especially benefited low-income households, which suffer the most from unemployment. Full Research Bulletin here https://t.co/MlMQO2BXxK pic.twitter.com/4DtpcOsqms

— European Central Bank (@ecb) January 30, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

After just months later, first the ECB pre-announced it would cut rates even more negative and resume QE, while the Fed waited a few months before its first rate cut in a decade, with some speculating that the Fed will cut all the way to zero and beyond.

In other words, the SF Fed was merely setting the stage for what comes next, or so we thought.

Or maybe not, because in an unexpected reversal, on Monday the same San Francisco Fed published an economic letter, titled “Negative Interest Rates and Inflation Expectations in Japan” which reaches a decidedly different conclusion: that contrary to economist expectations – and we highlight “economist”, because this conclusion would have been obvious to anyone with a semi-functioning frontal cortex – Japan’s negative rate experience “resulted in decreased, rather than increased, immediate and medium-term expected inflation.“

In other words, NIRP actually compounded the problem it was meant to address, and hardly the panacea that the San Fran Fed said back in February is what would have helped quicken the recovery.

Here is the summary from the paper:

After Japan introduced a negative policy interest rate in 2016, market expectations for inflation over the medium term fell immediately. This can be seen by assessing how prices for Japanese bonds with embedded deflation protection responded to the policy announcement. The reaction stresses the uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of negative policy rates as expansionary tools when inflation expectations are anchored at low levels. Japan’s experience also illustrates the desirability of taking preemptive steps to avoid the zero interest rate bound.

But… but… the San Francisco Fed in February said precisely the opposite.

Mocking intellectually challenged individuals, i.e. career economists, aside, here is the “unexpected” conclusion:

Because of the long period of low inflation in Japan, its experience provides an interesting example of the impact of negative monetary policy rates when inflation expectations are well-anchored at very low levels. We examine movements in yields on inflation-indexed and deflation-protected Japanese government bonds to gauge changes in the market’s inflation expectations from the BOJ moving to negative policy rates. Our results suggest that this movement resulted in decreased, rather than increased, immediate and medium-term expected inflation. This therefore suggests using caution when considering the efficacy of negative rates as expansionary policy tools under well-anchored inflation expectations.

Why, what a total and unexpected surprsie: almost as if nobody could have possibly foreseen that doing much more of the same will not only not lead to a different outcome, but will make the existing situation worse. Congratulations to at least the two SF Fed economists who “figured it out.”

And yet, we wondered, what may have prompted this shift, and the answer quickly presented itself when we thought of Mark Carney’s historic Jackson Hole speech in which the BOE head admitted that the days of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency are ending, and it should be replaced with an alternative (his laughable proposal was to have a “Synthetic Hegemonic Currency”, i.e. Facebook’s Libra become the world’s next reserve currency. While we are confident that Mark Zuckerberg would be delighted if he were to become the central banker to the world, the probability of such an outcome absent war is nil.

However, what was maybe even more notable in Carney’s speech was the following brief admission that everything that has happened in the past decade, every central bank policy pursued since the financial crisis has been a mistake. This:

Past instances of very low rates have tended to coincide with high risk events such as wars, financial crises, and breaks in the monetary regime.

So, let’s get this straight: for years, the general population has been told that only lower rates can spark an economic recovery, inspire higher inflation (as if that’s good) and lead to an economic rebound. Yet suddenly we find ourselves in an odd predicament, where years after a website called Zero Hedge warned that low rates and QE would lead to civil war in the US (a prediction for which it was roundly mocked), none other than one of the most respected central bankers warns that, wait for it, “low rates have tended to coincide with events such as wars and financial crises.”

So… we were right and these creatures were either clueless or lying all along?

As for the San Fran Fed, that absurd joke of a “research institution” which couldn’t see the housing bubble in 2006/2007 despite being smack in the middle of it when it was headed by one Janet Yellen, finally figuring out what we first said ten years ago – when we were broadly mocked as conspiracy theorists – all we can say is “who gives a shit.”

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com