China Injects Record Amount Of Loans In January

On one hand China is desperate to tell the world that this time it is taking deleveraging of the world’s largest and most indebted financial system seriously. On the other hand, it is doing this:

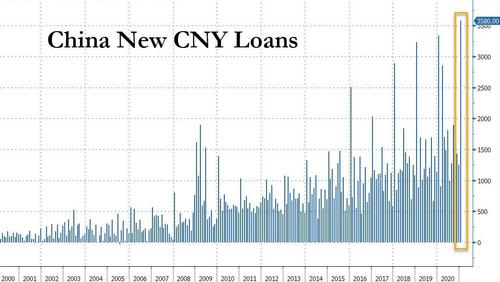

The chart shows that in January, China created a staggering, record 3.58 trillion in new yuan loans, a number which easily surpassed the previous record of 3.340 trillion set last January just as the Chinese economy shut down as a result of covid, when only gargantuan credit injections prevented a total economic collapse in the world’s 2nd largest economy. It’s almost as if only ever greater credit injections are keeping China alive.

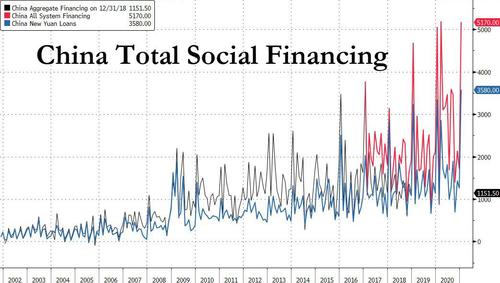

Because it wasn’t just new loans: the broadest Chinese credit aggregate, Total Social Financing which includes new loans as well as shadow debt creation and bond issuance, also exploded to a monstrous 5.170 trillion yuan, which at today’s exchange rate is roughly $800 billion.

That’s right: in one month China injected roughly 6 months of QE into the economy. And to think of all the praise Stanley Druckenmiller heaped just a few days ago on China for its “fiscal sanity”.

Here are the details:

- New CNY loans: RMB 3580Bn in January vs. consensus: RMB 3500bn. Outstanding CNY loan growth: 12.7% yoy in January; December: 12.8% yoy (12.1% SA ann mom).

- Total social financing: RMB 5170bn in January, vs. consensus: RMB 4600bn.

- TSF stock growth (after adding all government bonds) was 13.2% yoy in January, lower than 13.4% in December. The implied month-on-month growth of TSF stock accelerated to 12.0% (seasonally adjusted annual rate) from 7.8% in December.

- M2: 9.4% yoy in January (1.0% SA ann mom) vs. GSe: 10.0% yoy, Bloomberg consensus: 10.1% yoy. December: 10.1% yoy (2.6% SA ann mom estimated by GS).

So yes, anyone who only looks at the M2 – like Druck – would be left with the impression that China is barely adding to the Chinese debt. That would be dead wrong as nothing could be further from the truth.

As Goldman summarizes, the sequential growth of total social financing soared in January from a significant slowdown in December, mainly on decent loans growth, less drag from shadow lending (especially a rebound in banks’ undiscounted acceptance bills), and recovery in corporate bond issuance. How to read this conflicting signal amid China’s overall posture of urgent deleveraging? Well, if one listens to how Goldman justified it, this is just a Golidlocks scenario – the garguantuan amount of debt could have been even more Gargantuan:

Overall, as suggested by the Q4 monetary policy report and December’s Central Economic Working Conference, the PBOC will avoid sharp tightening to jeopardize growth recovery, but will also likely avoid too dovish a policy to prevent risks (e.g., financial leverage).

Goldman’s main points:

- The sequential growth of TSF picked up to 12.0% mom annualized sa in January, from 7.8% in December, mainly on decent loans growth, less drag from shadow lending (especially a rebound in banks’ undiscounted acceptance bills), and recovery in corporate bond issuance, despite a decline in net government bond issuance. In year-on-year terms, TSF stock growth moderated to 13.2% yoy in January. M2 growth decelerated to 9.4% yoy in January from 10.1% in December, in part due to larger-than-seasonality increase in fiscal deposits.

- Among major TSF components, new Rmb loans was decent in January, reflecting robust activity growth in manufacturing and construction suggested by January PMI data, and the government’s continued support for SMEs. Net increase in mid-to-long term loans to corporates was higher in January, and mid-to-long term loans to households also gained pace, although some news reports mentioned banks slowed the lending pace for mortgage loans. Banks’ undiscounted acceptance bills rebounded significantly in January (even after seasonal adjustment), partially due to lower interbank interest rates (though rates up in late January). Contraction in trust and entrusted loans also narrowed, in part due to smaller maturities. Corporate bond issuance recovered roughly to the average levels before the shock from bond defaults in November, while net government bonds issuance in January slowed notably. The government has delayed pre-allocation of part of local government special bond quota this year, and news reports seemed to suggest there remains a chance the government will pre-allocate part of quota to local governments.

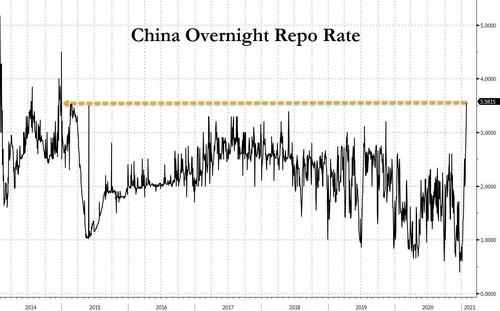

There is another reason why China injected such a massive amount of debt in the economy: the real reason. Recall that interbank interest rates in late January soared leading to concerns that PBOC may tighten monetary policy. Well, it was up to Beijing to ease nerves and to demonstrate that while rates won’t be cut, China can easily inject trillions into its economy, if needed.

It was needed, because the PBOC scrambled to inject enough liquidity to unfreeze the repo market (even as it still pretended that it was tightening conditions as part of its deleveraging) and as Goldman elaborates “in a monetary policy framework with policy rates increasingly emphasized as an anchor for market rates (DR007 in particular), this is more like a normalization of market rates to the average levels (fluctuating around OMO rates) prior to the shock from bond defaults in November, and accordingly narrow the deviation of market rates from the policy rate (OMO rate).”

And while a decent liquidity injection from PBOC and significant decline in interbank interest rates in December and early January helped corporate bond issuance recovery, it had also led to significant rise in leveraging in bond market. So to make sure the credit markets were well greased, China had no option but to flood even more new loans.

Goldman’s conclusion is that “as suggested by the Q4 monetary policy report and December’s Central Economic Working Conference, the PBOC will avoid sharp tightening to jeopardize growth recovery, but will also likely avoid too dovish a policy to prevent risks (e.g., financial leverage).”

Yawn. What the credit data really means is that Beijing continues to engage in a giant magic trick with the rest of the world, one where it pretends to shrink its debt even as it injects record amount of debt at the same time.

And yes, massive credit injections are all that really matter because on Wednesday, Chinese bank stocks outperformed in Hong Kong “after financial institutions offered a record amount of new loans last month” Bloomberg reported adding that half of the 12 biggest gainers Wednesday morning in Hang Seng Index are lenders, led by Bank of Communications rising as much as 4.3% while major banks also rally in mainland trading.

In other words, such an amount of debt was not expected, and should not have been expected if indeed China was doing as well as Beijing has been claiming.

In short: Beijing continues to lie about everything.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 02/09/2021 – 23:29![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com