Goldman Slashes Its Forecast Of “Build Back Better” Package Again, Now Sees Only $2 Trillion

With Congressional Democrats in disarray thanks to the relentless stonewalling of Steve Manchin, and the fate of Biden’s multi-trillion stimulus increasingly uncertain, overnight Goldman’s political analyst Alec Phillips cut the bank’s baseline forecast for the Democratic reconciliation to around $2 trillion from $2.5trn previously (and the $3.5trn initially proposed), as agreement among Democrats has been more difficult than previously anticipated.

Sen. Manchin has indicated he would prefer to keep the bill’s cost to less than $1.5 trillion, but has also said that he does not rule out supporting a bill in the $1.9 to $2.2 trillion range. Other centrist Democrats, like Sen. Sinema have also raised concerns about the cost of the bill but have been less specific in their public comments. Meanwhile, with House Speaker Pelosi recently saying the bill would cost “a couple of trillion”, it looks likely that the gross spending (including tax credits) in the bill will settle in the range of $2 trillion over ten years.

According to the Goldman analyst, the final outcome depends on 5 questions:

- How much will centrists be willing to increase the deficit?

- How much will congressional Democrats be willing to increase taxes?

- How much non-tax savings might be available (e.g., Medicare drug pricing reforms)?

- How much will Democrats rely on temporary benefit expansions? and

- How will the size of the bill be measured?

Below we excerpt from the Goldman note, drilling down on these five considerations, and concluding with a tentative timeline of what happens next:

1.How much deficit financing will centrist Democrats support?

In its budget submission to Congress earlier this year, the Biden Administration estimated that its fiscal proposals—the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan—would have increased the deficit by $800bn over 10 years. The budget resolution that Congress approved in August would have accommodated legislation increasing the deficit by as much as $1.7 trillion, though the House-proposed legislation looks likely to raise the deficit by much less than this (a formal cost estimate is not yet available). Centrist Democrats whose support will be necessary to pass the “Build Back Better Act” (BBBA) have insisted that the proposal be “paid for” through tax increases or spending cuts.

This is more of a subjective test than it might seem. “Dynamic scoring” would allow Democratic leaders to count extra revenues from the boost to growth the bill might bring about. In 2017, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated a $451bn dynamic revenue gain, enough to offset around a third of the $1451bn “static” cost of the bill. It is difficult to predict what growth effects the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) might attach to the BBBA, but it seems unlikely to offset more than a small fraction of the new spending in the bill. That said, the Treasury or White House might estimate larger offsetting gains. Overall, the legislation Congress enacts this year is likely to increase the deficit over the next ten years by several hundred billion dollars, but less than Goldman expected earlier this year.

2.How will the size of the bill be measured?

As noted above, several lawmakers have staked out positions on the size of the bill: Sen. Manchin has said his preferred top-line would be $1.5 trillion and some other centrists appear to share this view; Senate Budget Committee Chair Sanders has proposed $6 trillion, and other progressives have supported an even higher level.

However, by the time it reaches the House and Senate floors, the top-line of the fiscal package might not be as clear as some imagine.

The bipartisan infrastructure bill is a case in point. The bill would authorize roughly $536 billion in new spending by our estimate, but it is difficult to find an official document with this figure, as it requires assumptions regarding future appropriations levels and what spending might have otherwise been. The official cost estimate also reflects the provisions used to finance the bill, many of which cut spending. That bill is sometimes described as measuring $1.2 trillion, but the new spending is less than half of this, and the official cost estimate shows a cost of $256 billion over ten years. Despite that cost, many of the bill’s supporters describe it as “fully paid for”.

The top-line size of the BBBA is likely to face the same ambiguity. For example, tax cuts (for example, the non-refundable portion of the child tax credit or various investment incentives) could be netted out against the tax increases or counted toward the top line total. Spending reductions due to Medicare drug pricing reforms could be netted out against the spending figure or could be counted like the tax increases that are used to finance the proposal. The “cost” of the bill is likely to be a fraction of the top-line figures often discussed, assuming that it is financed in large part through tax increases and other budgetary savings.

3.How large of a tax increase will Democrats be able to agree on?

Assuming that some centrist Democrats oppose substantial deficit expansion, the size of the bill is likely to depend on the amount of tax increases and other budgetary savings that Democrats can agree on.

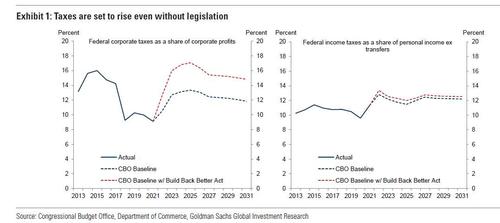

One challenge Democratic leaders face is that many of the tax cuts Republicans enacted in 2017 are already due to expire or phase down over the next several years (Exhibit 1 shows the projected tax receipts under current law and with the House-proposed BBBA). Nearly all of the individual tax changes enacted in 2017 expire after 2025, including the lower tax rates and limits on deductions (e.g. SALT). While the corporate rate reductions Congress enacted in 2017 were permanent, a number of other corporate policies become less generous. From 2022, corporate interest deductibility faces further limits and R&D expenses must be amortized over 5 years, and full expensing of equipment investment begins to phase out in 2023. In 2026, a number of international corporate tax provisions become more restrictive. This reduces the amount of new revenue that a repeal of those policies would produce over the next ten years and, in some cases, could take room in the bill if Congress faces pressure to delay or reverse them in this year’s legislation (e.g. restoring the SALT deduction or delaying the more restrictive corporate policies).

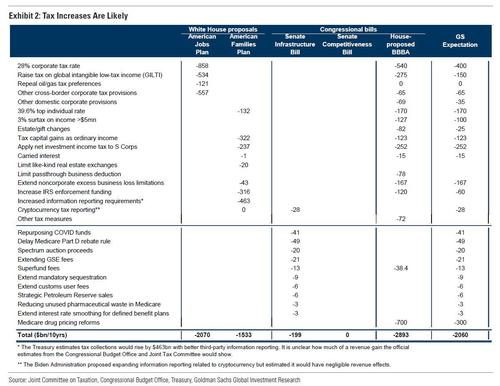

There are also serious political challenges to tax increases. Sen. Sinema, for example, has reportedly opposed raising tax rates, in particular. Over ten years, increases in the corporate, individual, and capital gains tax rates contribute $961bn of the roughly $2.9 trillion in savings measures House Democrats use to finance their initial proposal. Other centrists are likely to oppose tax increases beyond a certain point—Sen. Manchin has suggested the corporate rate should be 25%, in contrast to the House-proposed 26.5%, for example. We assume that most of the increases in tax rates that House Democrats have proposed will make it into the final bill, but there is clearly a chance that Democratic leaders will need to strip some out.

That would put more pressure on other, more technical, changes to tax policies. Beyond rate increases, the House bill would raise $1.15 trillion through other changes to tax rules, including:

- Tightening cross-border corporate tax policies. The TCJA reformed taxation of US companies’ foreign income, primarily through a new tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI). The proposal from the House Ways and Means Committee would increase the tax on GILTI income, by subjecting more of that income to the US corporate tax rate, reducing the ordinary returns companies could generate before becoming subject to the tax, and by shifting the calculation of the tax to a country by country basis, which prevents companies from averaging tax rates in high- and low-tax countries to avoid the US tax. These and related changes would boost tax revenue by an estimated $163bn/10yrs. A separate set of changes affecting cross-border income would raise another $176bn, for $339bn total. However, since many of these changes interact with the domestic corporate tax rate, if Congress leaves that rate unchanged at 21%, the total revenue boost from these changes might also be lower. Some centrist Democrats have also expressed concern about these provisions, though we expect that most will make their way into the final legislation though they might be scaled back from the current proposal.

- Other corporate changes. Beyond international changes, the Ways and Means Committee also proposed a variety of smaller changes that would primarily affect domestic corporate taxation, raising an estimated $84bn/10yrs.

- Pass through taxes. The Ways and Means proposal would impose the 3.8% net investment income (NII) tax on pass through income that is not subject to payroll or self-employment taxes. Separately, it would repeal the 20% deduction for “qualified business income” enacted in 2017. Together, these changes would generate an estimated $330bn/10yrs in revenue. Goldman expects that the NII change will make it into the final bill, but the 20% deduction for pass through income seems likely to face resistance and is more likely to be scaled back or dropped, we believe.

- Enforcement: Increased enforcement of existing tax laws does not contribute substantially to the new revenue in the House proposal, but this might become a more important part of the eventual fiscal package. As it stands, the House bill includes $80bn for enforcement activities but, for technical reasons, the resulting boost to tax receipts is not included in the overall estimate released by the Joint Tax Committee. However, CBO estimates that a similar proposal in the President’s budget would increase revenues by $200bn over ten years, or a net gain of $120bn.This is roughly half the net savings the White House estimates from additional enforcement funding.

- Tobacco taxes: The House proposal would raise $97bn in revenue from increased tax rates on tobacco products. In light of the White House pledge not to raise taxes on those with incomes of less than $400k, it could be difficult to keep this policy in the bill and it seems likely to be diluted or removed from the final bill.

- Estate tax changes: The House bill would reverse the increase in the estate tax exemption enacted in 2017. This seems likely to hit resistance in the Senate, and Goldman expects the final package to raise minimal revenue from estate tax changes

There are also a number of ideas that did not make it into the first draft of the House bill but could still emerge later in the process:

- A tax on corporate buybacks: Senate Finance Committee Chairman Wyden (D-Ore.) has proposed a 2% excise tax on shares that a company buys back. The House Ways and Means Committee proposal did not include a buyback provision, suggesting that it is less likely to make it into the final version of the bill. That said,the proposal could reemerge if Democrats are forced to scale back other sources of new revenue.

- Mark to market capital gains taxation: Sen. Wyden has also proposed to impose capital gains tax on a mark-to-market basis. Depending on the specifics, this could raise substantial revenue but would be administratively complex and seems unlikely to win the near-unanimous Democratic support necessary to pass.

- Partnership taxation: The Senate Finance Committee released a draft proposal to tighten taxation of partnership structures and increase enforcement of existing rules. Most of the changes are quite technical but the committee estimates they could raise $172bn over ten years.

- Bank reporting: Congressional Democrats are also considering the White House’s proposal to require financial institutions to report account transaction information tothe IRS, in an effort to track unreported income. The White House estimates that its proposal to require reporting for accounts with more than $600 would raise $463bn over ten years, but if Congress agreed on such a proposal it would likely apply only to accounts with an average balance of at least $10k, we believe. Overall, greater enforcement activity might help offset some of the cost of the legislation, but Goldman expects it to raise only a fraction of the roughly $700bn the White House estimates.

4.How much might non-tax savings provide?

The current version of the BBB Act would reduce Medicare drug spending by around $700bn over ten years, more than it would raise from increasing the corporate tax rate. Of this, around $150bn would come from repealing a Trump Administration rule related to Medicare drug rebates, with the remainder coming from Medicare price negotiation and related policies.

At least a few Democrats in the House and the Senate have gone on record with concerns about changing Medicare prescription drug pricing, which in its fullest form was projected to produce budgetary savings on par with the 26.5% corporate tax the House has proposed. Drug pricing reforms are generally popular, with 83% of the public (95% of Democrats) supporting Medicare price negotiation, so it could be difficult for members of Congress to oppose the broader bill on those grounds. Nevertheless, it seems likely that savings from Medicare drug pricing changes will be limited to less than $300bn (of which more than half would come from repealing the already-postponed rule noted above). Speaker Pelosi acknowledged as much recently, saying: “We’ll get something of that, but it won’t be the complete package that many of us have been fighting for a long time.”

Outside of drug pricing, there are potentially savings in other areas of health care, but neither the White House nor congressional Democrats have proposed them. In previous legislation to expand health insurance benefits, like the Affordable Care Act (ACA), cuts to Medicare reimbursements rates have provided substantial budgetary savings to offset new costs, but congressional Democrats seem unlikely to lean heavily on such cuts this year, we believe, in light of the continued public health crisis and the fact that these cuts are generally much less popular than the drug pricing changes they would be replacing.

Beyond health care, there are few obvious options for additional savings that nearly all Democrats could agree on. The bipartisan infrastructure legislation that is awaiting a vote in the House includes roughly $200bn in less controversial savings provisions to offset part of its cost, including the repurposing of COVID-relief funds, leaving little on the table for the reconciliation bill.

5. Will the bill do “fewer things well” or make policies temporary?

Another way Democratic leaders might fit more policies into a smaller package is to make more of them temporary. Policies that might cost $4 trillion over ten years would likely cost less than $2 trillion over the next five years, if set to expire thereafter.

The House-proposed BBBA already phases out some policies after several years to reduce the reported cost of the bill. The prime example is the $130bn/yr expanded child tax credit, which is extended only through 2025 at a cost of $556bn/10yrs. Universal pre-kindergarten and new higher education subsidies phase down over several years through 2028. Making all of these policies permanent would add more than $1 trillion to the ten-year cost of the bill.

It seems likely that the benefit expansions in the final BBBA will be largely temporary. When asked how she believes Democrats will manage to fit their priorities into a smaller bill, Speaker Pelosi recently commented “that the timing would be reduced in many cases to make the cost lower.” Congressional Progressive Caucus Chair Rep. Jayapal has explicitly endorsed this strategy as well.

That said, Speaker Pelosi has also said that Democrats might try to “do fewer things well” rather than spreading funds across many programs. House Budget Committee Chairman Yarmuth (D-Ky.) summed up the choice as “… either to try to keep all the elements and pare them down, or to focus on three or four most important elements…my guess is we’ll probably try to keep all the elements and pare them down.”

What this likely means in practice is that Democrats might drop a few elements of the package and fund the remaining ones for several years instead of permanently. It might also lead to greater means-testing of some benefits, which would reduce costs and might increase centrist support for some provisions.

What a Compromise Might Look Like

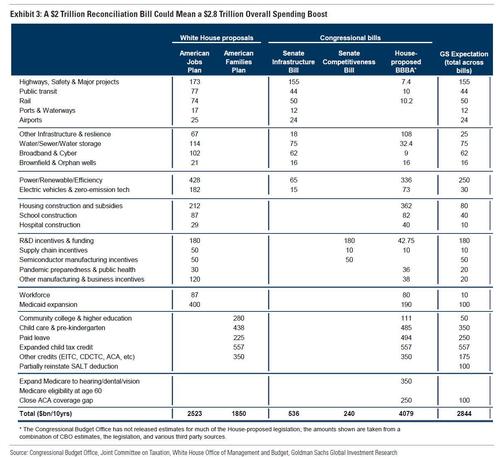

To examine what a compromise might look like, Goldman first estimated what the current version of the House-proposed legislation would spend each year, using a combination of CBO scores for the few pieces of the bill that have been estimated, White House estimates where the policies appear very similar to the House bill, and the bank’s own rough estimates for areas where neither is available. It then construct a hypothetical bill that reduces or eliminates some provisions that appear to have less support and set several others to expire after 2025.

The hypothetical bill is constructed in this way for two reasons. First, the White House and Democratic leaders have already decided to let one of the highest-profile provisions, the expanded child tax credit, expire after 2025. This aligns the expiration with the expiration of several other important tax provisions, and also puts it just after the next presidential election.

Second, a number of major provisions in the House bill like child care subsidies, universal pre-k, and higher education subsidies, are already set to expire after 2028, so there might not be that high a hurdle to setting the expiration date sooner. As shown in Exhibit 3, a reconciliation bill costing slightly more than $2 trillion over ten years would lead to a total of around $2.8 trillion when counting the bipartisan infrastructure bill that the House looks likely to pass before year-end and the competitiveness bill that includes several components of the President’s American Jobs Plan (the Senate passed the bill earlier this year, but the timing for House action is unclear).

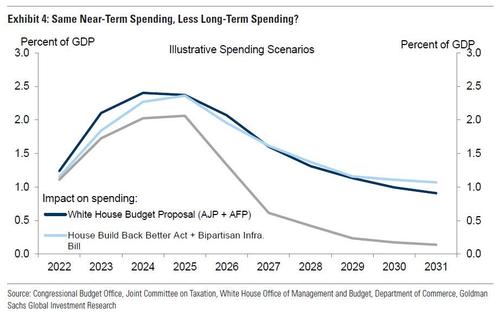

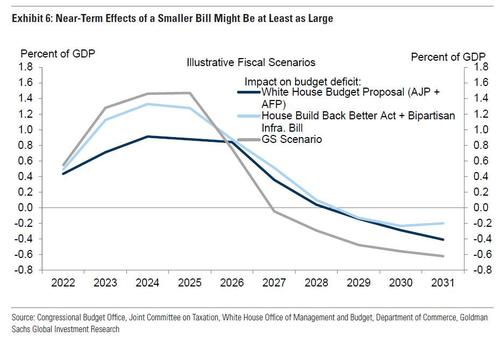

The impact on the medium-term economic outlook depends less on the ten-year cost, however, and primarily on the amount of spending over the next few years. Exhibit 4 compares White House projections of its proposals’ costs, to Goldman’s rough estimate of the House bill and a scenario we have constructed that sets most of the key provisions to expire after 2025 and then dials back the size further to bring the new spending under the bill to around $2 trillion over ten years.

The upshot is that spending would be slightly lower than under the White House proposal or the House-proposed version, but it is possible to fit most of the main priorities into a $2 trillion bill if they are set to expire after 2025. The main exception is the Medicare benefit expansion that congressional Democrats have proposed. Under the House bill, the most expensive addition to coverage—dental insurance—does not begin until 2028, presumably to keep the 10-year cost of the bill down. It seems more likely that Democrats will drop this particular provision, instead.

In all three scenarios, a similar amount of spending would take place in the first half of the ten-year window that Congress uses. But since tax increases and other savings measures would generally be more evenly distributed over the next ten years, the lower amount of tax increases needed to offset the ten-year cost of the proposals could mean that the combined effect might be a larger increase in the deficit over the next few years than the White House proposed or the preliminary House proposal implies

In any case, over the next few weeks the outlines of the fiscal package to become clearer. There are a few deadlines that might force decisions to be made:

- October 31: The surface transportation program expires on this date. The bipartisan infrastructure legislation would address this, so the date is likely to serve as a new deadline for a vote on that bill. As progressives have indicated that they will oppose the infrastructure bill until they have clarity on the Build Back Better Act—this could mean Senate passage, or it might mean a publicly-agreed framework—this deadline could serve as a forcing event for decisions on the broader fiscal package. However,with little time left before that date, it looks likely that Congress will enact another temporary extension.

- December 3: The continuing resolution that Congress passed in late September to extend government spending authority expires December 3. The $480bn debt limit increase that Congress passed last week was also meant to put the new deadline around this date, though there is a fair chance it might last slightly longer. If the debt limit does become binding around this time, it might also serve as a deadline for an agreement on the broader fiscal package, as both are likely to pass via the reconciliation process.

- December 31: At the end of the year, a number of policies expire. Expansions of the child tax credit, the earned income tax credit, and other provisions enacted earlier this year are set to end, and these expirations will likely drive an agreement if congressional Democrats have not already reached one.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 10/19/2021 – 13:45![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com