Goldman: Another Fiscal Package Next Year Appears Likely

Commenting on Friday’s passage of Biden’s BBB bill, Goldman’s Alec Phillips writes that the Biden fiscal agenda took two steps forward over the last week, as the President signed the “hard” infrastructure bill into law and the House passed its version of the “Build Back Better” (BBB) legislation. That said, those were arguably the easier parts of the legislative process and the hard part now begins, and according to Goldman, “Democratic leaders are likely to face a more difficult task in getting the BBB legislation through the Senate, and changes there look likely.”

For one, Senate rules look likely to preclude some policies in the House bill. Some policies in the House-passed legislation are likely to violate Senate rules regarding what may be included in reconciliation legislation. Immigration policy changes, in particular, are likely run afoul of the “Byrd Rule” in the Senate, which prohibits provisions whose fiscal effect is “incidental to” the primary purpose of the provision. If these provisions are removed in the Senate, as seems likely, this would reduce net spending in the bill by around $115bn over 10 years.

The political realities in the Senate are likely to lead to other changes. As Phillips explains, there are several items in this category, and there will probably be additional issues that arise over the next few weeks as the Senate debates the bill. Among the new benefits the bill provides, the most obvious areas where one or more Senate Democrats might object include:

- Paid leave. After negotiations with centrist Democrats in the Senate, the White House omitted from its framework its prior proposal to provide a new federal benefit for paid leave. However, the House added the program back into its version, raising the cost of the bill by around $200bn. Sen. Manchin (D-W. Va) has indicated that he opposes a benefit program like the House proposes, and the Senate will likely scale back paid-leave benefits or remove them entirely from the bill.

- Infrastructure and climate spending. The House-passed BBB legislation has around $28bn in “hard” infrastructure spending and tens of billions in funding for electric vehicles, on top of the amounts in the recently enacted infrastructure bill. There will be likely be some centrist Democratic opposition to including provisions that were supposed to have been dealt with only in the earlier infrastructure bill.

- State and Local Taxes (SALT). The House-passed bill would allow taxpayers to deduct $80k in state and local taxes, up from $10k today, a tax holiday for the rich. The Senate looks likely to change the provision, potentially by fully reinstating the deduction for individuals with income under $400k or $500k and leaving the $10k cap in place for those with higher incomes. At this point, something along the lines of the potential Senate policy looks like the most likely outcome, though some combination of the two ideas also seems possible.

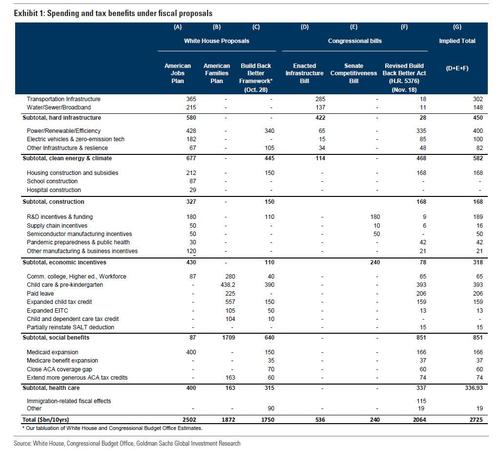

The chart below shows Goldman’s comparison of fiscal proposals with new estimates of the House-passed legislation

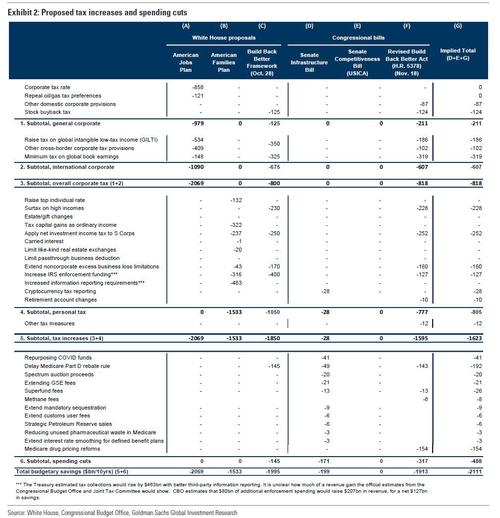

Goldman then argues that how the legislation offsets the cost of new spending could also change. Some revisions to the policies Democrats would use to pay for the legislation also seem likely, though it is less clear how these might change. Among the possibilities are:

- Minimum tax on book income. The House-passed legislation includes a 15% minimum tax on book income, which President Biden proposed earlier in the year but had been put aside until recently. Taxing companies based on their financial statement income would represent a major step away from the current system that relies only on tax returns, and it could face some resistance in the Senate. While some version of this tax will likely make it into the final version of the bill, there is a greater chance that it will be changed or removed from the bill in the Senate than most of the other corporate tax increases. If the Senate did opt to drop the minimum tax proposal, it could reopen the debate on a modest corporate tax rate increase, though this does not appear very likely at the moment.

- Surtax on upper incomes. The House proposal to impose a 5% surtax income over $10mn and another 3% on income over $25mn (for a total of 8%) will likely also change in the Senate, though it looks very likely that something similar will be in the final package. It is conceivable that another smaller surtax could be applied at a lower level of income in order to offset a broader SALT deduction, for example.

- Drug pricing. Further changes to the Medicare drug pricing changes in the Senate are possible, as the affected industries are likely to continue to seek modifications in the 50-50 Senate. Again, the final bill is expected to follow the general contours of the House bill in this area, but incremental changes seem possible.

A major complaint many have lodged against Biden’s BBB is that it uses a lot of timing gimmicks to reduce its true cost.

To wit, with much of the bill spending likely to be front-loaded, some centrist Democrats will likely oppose the extent to which the House bill front-loads new spending, primarily by setting some policies to expire after 1 year (e.g. expanded child tax credit and earned income tax credit extension), 3 years (e.g. health insurance subsidies), or 6 years (e.g. child care and pre-kindergarten benefits). As shown in Exhibits 4, 5, and 6, the spending in the House bill is indeed more front-loaded than the tax increases and other means of offsetting the cost, which are slightly back-loaded over the 2022-2031 period.

The Senate version of the bill will likely be a “little less” front-loaded than the House version. Sen. Manchin has described some of the strategies the House bill uses as “shell games and gimmicks” and is expected push to reduce them in the Senate. That said, even if there are changes along these lines, expect only a modest effect on spending over the next few years. Some of the policies that the Senate might drop from the bill, like paid leave and immigration changes, have little impact over the next couple of years but removing them would make room to extend other policies for longer than they last under the House bill.

Goldman also argues that it could be tough for lawmakers to set a hard limit on the top line amount of spending in the bill. Specifically, Sen. Manchin along with Sen. Sinema (D-Ariz.) have also suggested that new spending in the bill should be kept below a certain level—somewhere between $1.5 trillion and $1.75 trillion. However, the “size” of the bill is somewhat subjective. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimate shows $1.64 trillion in new spending, similar to the range that centrist Democrats in the Senate have implied they might support. But that spending number omits more than $200bn in climate-oriented tax credits and nets $260bn in drug pricing changes (i.e., spending reductions) against the new spending. Taking those items into account, the new spending and tax benefits in the House-passed bill totals slightly more than $2 trillion over 10 years.

If the Senate removes the House provisions on paid leave and immigration, the adjusted total would drop to around $1.75 trillion/10 years. Since the Senate might redirect some of these funds to other purposes, Goldman estimates that a total of $1.75 to $2 trillion over 10 years seems likely. Of course, the official CBO estimate of spending will probably be at least a few hundred billion below the actual amount of new spending and tax benefits because that’s what the CBO does.

Another touchy topic is that the White House has made assurances that the legislation will not add to the deficit, but that is also subject to interpretation. CBO estimates the House-passed bill would raise the deficit by $367bn over 10 years, but this omits $207bn in increased revenues from increased funding for tax enforcement, suggesting that the bill would raise the deficit by only $160bn over 10 years (less than 0.1% of GDP over that period). The White House contends that tax enforcement would raise revenues by $400bn or more, which would mean that the bill would actually reduce the deficit slightly over ten years if true.

Then there is the issue of bill passage and timing, and here a big wildcard is the debt ceiling, which will have to be addressed some time in late December. According to Goldman, the debt limit could delay Senate action on the BBB bill, or accelerate it, depending on how Democrats choose to address it. The two parties have taken the same positions ahead of the next debt limit deadline as they did ahead of the last one—Democrats believe Republicans should support a debt limit increase under “regular order” while Republicans believe Democrats should raise it alone via the reconciliation process. While their positions are the same, comments from Democratic lawmakers suggest somewhat greater openness to addressing the issue via reconciliation than the last time around, and we think this is the more likely approach.

To use the reconciliation process, Democrats would need to first revise their budget resolution for fiscal year 2022, which already includes instructions for the BBB bill but does not instruct the relevant committees to raise the debt limit. Once Congress has revised the budget resolution, Democrats would then need to decide whether to pass a standalone debt limit increase or to combine it with the broader BBB bill. A standalone reconciliation bill could take several days to pass unless Republicans agree to an expedited process. Combining the debt limit with the BBB bill would be more efficient—it could even create a deadline for BBB passage in the Senate—but would have the disadvantage of directly linking the debt limit to the major fiscal legislation. At this point, separate bills seem more likely but either scenario is possible

One final point: as Phillips concludes, another fiscal package next year appears likely: According to the Goldman strategist, “as the final version of the BBB takes shape, discussion of another fiscal package has already begun.” The one-year extension of the expanded child tax credit (CTC) and earned income tax credit (EITC), through 2022, is likely to lead congressional Democrats to prepare legislation to extend it further. Goldman thinks that it is more likely than not that Congress extends the expanded child tax credit past 2022, though there is clearly some risk that it expires at that point. Congressional Democrats might also try to pass legislation to address some of the policies that do not make it into the BBB legislation, like a federal paid leave benefit or Medicare expansion. And while it is hard to rule out another (much more modest) fiscal package next year, Goldman would be surprised “if Congress manages to do much more than extend expiring policies at that point.” We, on the other hand, would be surprised if Congress does not manage to pass another substantial fiscal package, especially if we see a “surge” in covid cases into the winter with Democrats claiming that hardships will require another round of stimmies. Not surprisingly, the pieces are all starting to fall into place, with this headline hitting late on Monday:

- 7-DAY DAILY CASE COVID CASE AVERAGE ROSE 18% FROM WEEK EARLIER

This looming deflationary threat is also why anyone who really thinks the Fed will hike rates not once but twice in 2022 – an election year – may want to consider taking it easy on the booze and/or hard drugs.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 11/22/2021 – 20:40

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com