The David Einhorn Podcast: The Fed Is Monetizing Debt Again

It was back in 2012 that famed contrarian and value investing hedge fund icon, David Einhorn, first took aim at the pinnacle of market manipulation when he slammed the Fed for creating the ultimate toxic cocktail: something he called the Jelly Donut Policy. As the Greenlight founder wrote in May 2012, the Fed is “presently force-feeding us what seems like the 36th Jelly Donut of easy money and wondering why it isn’t giving us energy or making us feel better. Instead of a robust recovery, the economy continues to be sluggish.”

Seven years later, the recovery is just as sluggish and yet nothing has changed; in fact, just two months ago, the Fed launched what Fed Chair Powell sternly refuses to admit is QE4 but… is QE4. And while Einhorn has been right that the Fed is ultimately destroying the very fabric of not only the US economy, but taking down society with it as the growing wealth and income disparity chasm will eventually culminate in civil war, by fighting the Fed, Einhorn has seen his AUM plummet in recent years, his hedge fund a shadow of what of what it once was, largely due to the relentless ascent of the so-called “bubble basket” of stocks, those names which benefit entirely due to the Fed’s monetary generosity, and which have seen their stocks prices explode in the past decade.

Which brings us to another Jelly Donut – that’s the name of a new podcast service, which in recent weeks has interviewed, Julian Brigden, Ben Hunt, Miles Kimball, and others. Most notably, among those interviewed is that man responsible for the concept in the first place: David Einhorn.

While David Einhorn has recently been in the press for yet another feud he is currently waging, this time with Elon Musk, in which he first accused the Tesla CEO of “Significant fraud”, followed up with even more specific accusations of accounting irregularity profiled here, in the podcast with Ryan – which marked the Greenlight CEO’s first appearance in two years – Einhorn goes back to his roots and takes on his primary nemesis, the Federal Reserve, which is why among the topics covered are QE, ZIRP, MMT, fiscal and central bank stimulus. Oh, and gold, because seven years after the “Jelly Donut policy” was first coined, Einhorn remains just as bullish on the precious metal as the following excerpt confirms:

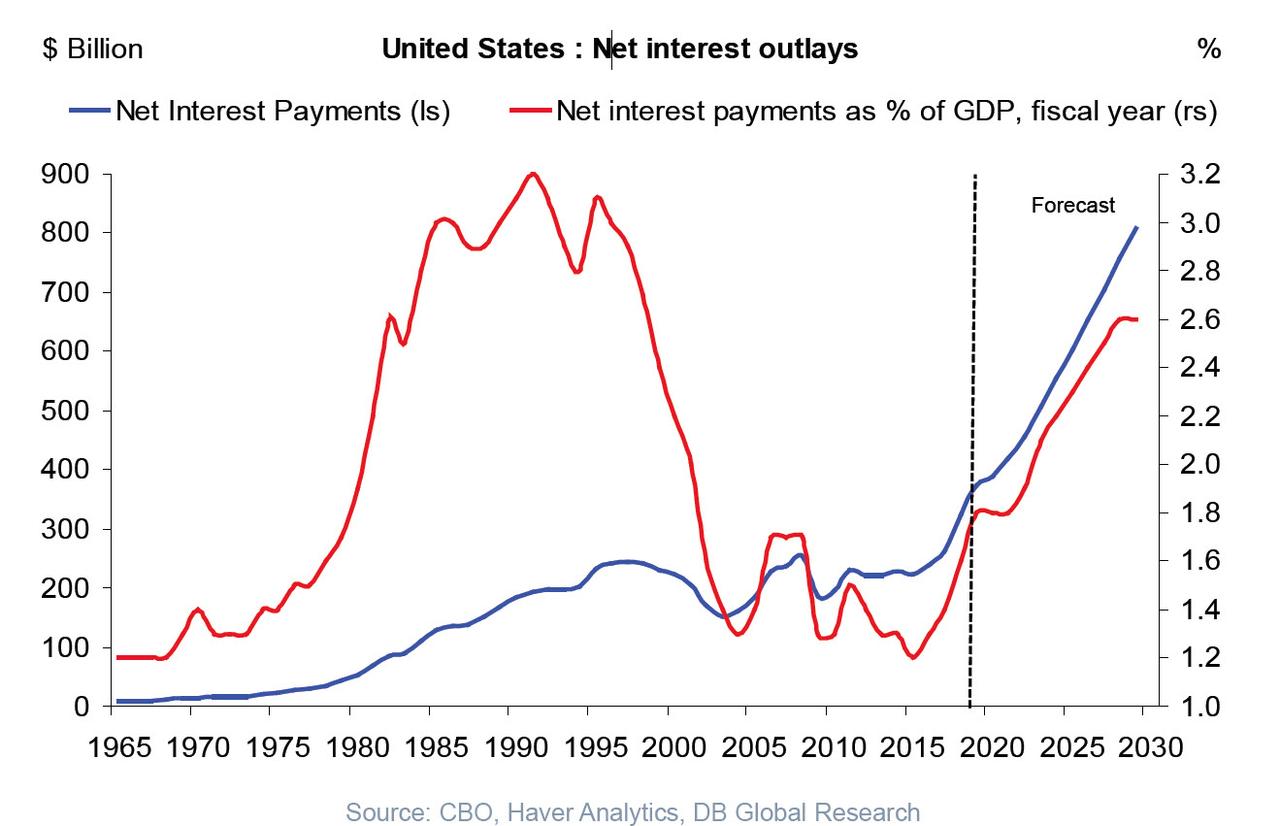

We’re running a very high deficit to GDP. And this is many years into an economic recovery with something that’s very close to full employment… In the event that the economy weakens, there’s going to be an enormous, both natural fiscal stimulus that comes from higher benefits, and less tax revenue, as well as an urge for Congress to do things to help people out in tougher economic times. So, what you have is a deficit right now that is very high and then you combine that with an accumulation of debt. You have a situation where the debt to GDP is much higher going into whatever the next down cycle is, and where we’ve had before similarly you have of monetary policy, which has been very aggressive. The balance sheet is much larger than it used to be and the rates going into down cycle are much lower than they used to be. There will be enormous pressure on the central bank to be very aggressive. And, so when you combine aggressive fiscal policy with aggressive monetary policy, historically that can lead to a problem with the currency and then when you realize that the same dynamic is essentially in place and in some cases worse in all of the other major developed currencies, it seems to me it’s a situation where sooner or later it might be good to have a fraction of your assets in gold, which is not subject to appropriation by the whim of the central banks.

Or rather, it is not yet subject to appropriate by central banks. Because all it takes is another Executive Order 6102 for all that to change.

All this and much more in the podcast below (phonetic transcript attached below):

Transcribed:

Ryan: David welcome to the podcast.

David: Hi Ryan. Thanks for having me.

Ryan: Well, it’s great to have you here. Really appreciate you coming on. First off, I wanted to explain a little bit to the audience of why we have you here, and when I decided to launch this podcast, I was trying to think of a great name that captured the subject of the show everything related to macro and monetary policy and I immediately thought about your article. So, going back to 2012 you wrote an article called The Fed’s Jelly Donut Policy in The Huffington Post and used a story about The Simpsons to explain a long periods of QE and zero interest rates may actually be harmful to the real economy. And it turns out a lot of what you said, they’re panned out inefficient allocation of Capital stock Buybacks with no urgency for corporations to invest to reach for yield from all investors, especially to Retirees so a lot has happened since then take us back to the feedback you got from the article and if your views have changed since.

David: Well honestly, I think the best feedback I got from the article is somebody’s naming their podcast after it. How can how can you beat that? And I’m honored to be here for the first one of these and I expect after I speak today, you’ll probably get all kinds of feedback and I will hopefully learn from listening to the feedback you get because I’m not a trained Economist. I’m not a macro-economist, I’ve never worked in the plumbing of the fed or any of these things. I’m basically an equity Market investor, and I think I have a few observations on some of these things from time to time, but I don’t profess to be a technical expert in all the mechanics of everything.

Ryan: Right and what was considered unconventional monetary policy over decade ago is really now seen as normal not just for the FED but central banks around the world and these policies seem to only be going on for longer and longer and uh others talked about using these tools and definitely what’s your view on these policies as far as do you ever imagine that balance sheet still being over $4.5T, you know taking up towards there right now and before the crisis was $800B. Did you see this still going on this long? And what’s your thoughts on the Fed using these tools and definitely?

David: Yeah. I don’t know how to predict what the FED is going to do with the size of the of the balance sheet, you know, basically, I think there’s two main parts of fed uh policy one is the interest rate policy and then the uh other is the balance sheet size the main thrust of the jelly donut thesis is that the interest rate policy by setting rates too low at some point you have a diminishing return from lower rates and eventually ultimately a marginally negative return from low rates, which is kind of separate from what you just raised which has to do with the size of the FED balance sheet and the monetary base and how they choose to implement that.

Ryan: Yes, so separating those out a little bit, obviously with the all the easing, you know, short-term rates, they’re able to target and bring down low and now we’re having some issues in the repo Market obviously some change some things change with paying interest on excess reserves and there’s been some other issues that brought up as far as the tax bill and things like this. What’s your thoughts right now on the current issues with the repo market and can the Fed really keep a hold of rates at this point?

David: Well, I think the FED ultimately can control whatever chooses to control within certainly within rates or whatever markets it’s willing to intervene in because it has unlimited fire power in order to enforce whatever policies that it wants . Sometimes eventually if the fed or a central bank over overdoes it, then people can take it out on the currency, which would be the normal reaction, but within the domestic economy in terms of control…. The Fed can set any rate that wants actually almost anywhere on the curve by, you know directly intervening in the market with unlimited firepower.

Ryan: Right, and going back to a Bloomberg interview did in 2014, you told a story about how you ask Ben Bernanke and a private dinner about QE and he talked about how these policies would lead to higher inflation talking about usually it only happens after a war and he talked about Japan has done a lot more QE than the US and they don’t have inflation. Recently Fed officials have said it’s kind of a mystery why. CPI claims inflation hasn’t gone up more but we have seen inflation in certain pockets: Healthcare, Housing, College tuition and you mentioned the currency piece. So what’s your thoughts as far as, where inflation goes and how long it can actually stay where it is right now?

David: When the Fed creates money and whether it’s from what you would call money printing or what they want to call quantitative easing, and most recently they’re doing the same thing and they want to tell us that it’s not quantitative easing. I don’t really know what the difference between all of these things is except for semantics and messaging in an attempt to, kind of control things. When the Fed increases the money the money has to go somewhere. It doesn’t have the same impact that it did when there were fewer excess reserves in the system, but we can come back to that later. I’ll just skip over that for the moment, but when they create money, the money does have to go somewhere. Now, the thing is, they don’t have any control over where that is. So it could be that the price of corn goes up or it could be the price of healthcare goes up or it could be the price of stocks go up or the price of bonds or art or Real estate or oil or what not but it doesn’t have to be any of those particular things. So as price levels in general go up it may or may not be prices that are measured within the CPI basket, which is only, you know, its a subset of possible places where new money can go.

Ryan: That makes sense. And you mentioned kind of the mechanics of how QE works. So one camp says that this is just an asset Swap and that this is a swap for bank reserves for Treasuries, and this is kind of normal operations. Where the other camp says this is something more like money printing and really something like debt monetization since all the interests gets remitted back to the Treasury and the so far a lot of these assets haven’t actually rolled off. How do you actually view that piece?

David: Yeah. I think it’s a little bit of a semantic game. By only looking at one side of a transaction, in other words, like what happens after a treasury is issued, you can decide, you know, that this isn’t money printing. But when you think about it in the totality how do treasuries get issued, a treasury is issued because the government needs to borrow money. And when the government needs to borrow money, there’s two places they can borrow it. They can borrow it in the private sector or effectively they can borrow it from the central bank. Now, there’s a rule that says they can’t sell the debt directly to the central bank, so they instead issue a T-bill to a leading commercial bank and then the central bank can buy the T-bill and you’re kind of in the same place. What’s happened is that the Federal government has borrowed money and ultimately that loan is held by the central bank which increases the central bank’s balance sheet size and thereby in there for the monetary base. So it’s the equivalent of a debt monetization. When you question whether its quantitative easing whether the current Fed chairman says it’s something different from that , whether it’s money printing, it’s really all the same things because all it is, it’s the Fed increasing the size of its balance sheet by buying Treasuries in one form or another. The difference is some people want to look at it as a two-step thing where the treasuries are issued by the Treasury Department to the private sector and then the Fed buys it as opposed to the Treasury issuing it directly to the Fed which is illegal, but the fact that there’s two steps in the transaction—I don’t think it makes any economic relevance. So think you have to look through it and when you look through it, when the Fed buys Treasuries, they’re increasing the balance sheet. They’re increasing the monetary base and effectively its debt monetization.

Ryan: Right, that makes a lot of sense. Now going back to interest rates and kind of what your article focused on, it’s arguable that interest rates are really the price of money and the price of money has been manipulated. Now, as far as rates rising on the longer end, you mentioned the Fed can kind of control not just the short-end, but also the longer-end. We saw recently when the repo market spiked up to a 10 from 2, that people said, okay, the price of money is not really what the Fed says is it is the price should be this. So, the question is, could the Fed lose control as far as people losing faith in their ability to just start tinkering and really micromanage. And will that show up maybe on the long end of the curve or how could that crisis of confidence happen?

David: I don’t know that you’ll have a crisis of confidence. But when you think about what just happened in the repo Market essentially, there wasn’t a huge amount of active intervention in the exact moment that it spiked. It spiked and the Feds saw what was happening relatively quickly after and announced new programs with extraordinary firepower in order to make sure that the problem doesn’t persist and that’s what I mean by their having the ability to control the rate. So, it spiked for a moment, but beyond that, you know, they managed to put it back together. As for Relating to the long end the curve, it has to do with how much intervention this the Fed is willing to do. Presently, I don’t know that they’re doing a lot of intervention on the long-end, but if you look at other central banks around the world, Japan and Europe and so forth, there’s huge amounts of intervention at the long-end of the curve and those banks have effectively cornered and controlled those rates as well.

Ryan: Yeah, that’s interesting when you look at Japan buying up huge amount of the JGBs is outstanding and obviously buying ETFs and things like Apple stock and seemingly distorting markets and doing so. Now, going back to the article again, the thesis laid out talking about with the Simpsons, it was actually really enjoyable to read for people who are trying to understand how this is all working. And, I think when you look at retirees, when you look at savers and obviously pension plans and insurance companies, a lot of these types of things have really caused a big problem as far as rates being low, and obviously for all investors going out on the curve to bid up risk assets. Do you see a path to normalization as far as rates or concerned? And what should the Fed be doing right now, and can they normalize rates or should they right now?

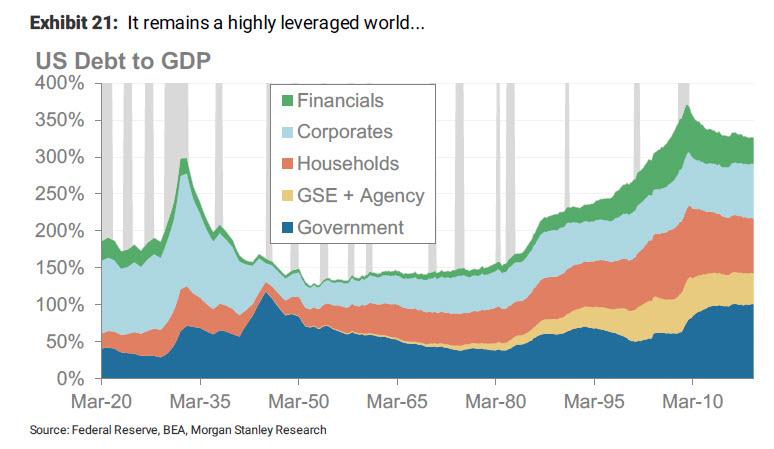

David: Well, I think it depends on what one thinks about as normalized rates. We’re certainly in a situation that there’s a lot more leverage in the financial system than 20 or 30 years ago, which means that the debt that’s in the system can’t support nominal rates that are higher than a certain amount, you know, if you think about what the deficit looked like when Volcker raised the short rates up into the teens, the debt to GDP was nowhere near what it is today. So you didn’t create a question about the government’s ability to repay the even in as rates went even a short rates went up at a at a good clip and ultimately even cost for long bonds. They wanted to sell at the time became quite expensive right once you have debt to GDP or incorporate case debt to EBITDA at higher ratios. It becomes much more sensitive to increase rates in terms of, from a solvency perspective. And so the situation is much different today than it used to be.

Ryan: Yeah, I’m looking at equity markets, especially here in the U.S., when you look at share buybacks and other things that have been going on. How are you looking at this the market based on these share buybacks uh and a lot of people have been talking about it. We’ve seen this many times before and it’s only a matter of time until the cycle has turned and you’ve talked a little bit about this over the past couple of years, but it really seems we’re almost kind of out of breaking point. How do you feel about the market right now?

David: I have no opinion as to whether the market is anywhere near a breaking point. Not the type of forecasting or thinking about things that I think about, you know, and in terms of things like share repurchases from my perspective, they are a tax efficient way to return capital and businesses to their owners and to the extent that there aren’t investment opportunities at better returns than returning capital to their owners, I think it’s a perfectly appropriate thing for businesses to do.

Ryan: Okay, that makes sense and you mentioned as far as going back to 2008 and even previous with the derivatives and all the debt built up in the system. How are you looking at the current environment compared to 2008. Obviously, it was built up more so in the mortgage market. How are you looking at the market now compared to back then. We now have some of these banking regulations after Dodd-Frank and others. Are we actually worse off or more levered up?

David: Well, there’s leverage, but the leverage is in a different place than it was last time last time. I believe (in 2008) that the leading part of the leverage was in the real estate market both commercial and residential and I think today it’s more in the public market meaning sovereign debt, municipal debt, and also corporate debt.

Ryan: Right and we’ve seen corporates levered up to some of the highest they’ve been…The last thing to touch on is, you’ve held a position in physical gold for a while now. Other investors have talked about hedging against inflation or even a “Black Swan” type event with real assets. How are you seeing a position in real assets as far as hedging against inflation?

David: Yeah. I don’t know that it’s a hedge against inflation or a particular Black Swan event. But, our theory relating to gold is that monetary and fiscal policies combined are very aggressive. Just take the United States as an example right now. We’re running a very high deficit to GDP. And this is many years into an economic recovery with something that’s very close to full employment… In the event that the economy weakens, there’s going to be an enormous, both natural fiscal stimulus that comes from higher benefits, and less tax revenue, as well as an urge for Congress to do things to help people out in tougher economic times. So, what you have is a deficit right now that is very high and then you combine that with an accumulation of debt. You have a situation where the debt to GDP is much higher going into whatever the next down cycle is, and where we’ve had before similarly you have of monetary policy, which has been very aggressive. The balance sheet is much larger than it used to be and the rates going into down cycle are much lower than they used to be. There will be enormous pressure on the central bank to be very aggressive. And, so when you combine aggressive fiscal policy with aggressive monetary policy, historically that can lead to a problem with the currency and then when you realize that the same dynamic is essentially in place and in some cases worse in all of the other major developed currencies, it seems to me it’s a situation where sooner or later it might be good to have a fraction of your assets in gold, which is not subject to appropriation by the whim of the central banks.

Ryan: Right, that makes a lot of sense. Well David, thank you so much for coming on, I really appreciate it.

David: You’re welcome and good luck with the whole podcast series.

The full podcast can be found here.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 12/07/2019 – 23:38

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com