Is Hong Kong’s Outrageously Expensive Housing Fueling Civil Unrest?

An important backdrop to the ongoing anti-government / pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong is the widening wealth gap between the city’s billionaire developers, and fed-up citizens trying to carve out an existence amid an outrageous cost of living.

To that end, Bloomberg‘s Shawna Kwan notes: “Widening inequality has long contributed to tension in the city, and nothing exemplifies the divide between the haves and have-nots better than the sky-high cost of residential property.“

As Kwan continues, via Bloomberg:

1. Just how expensive is property?

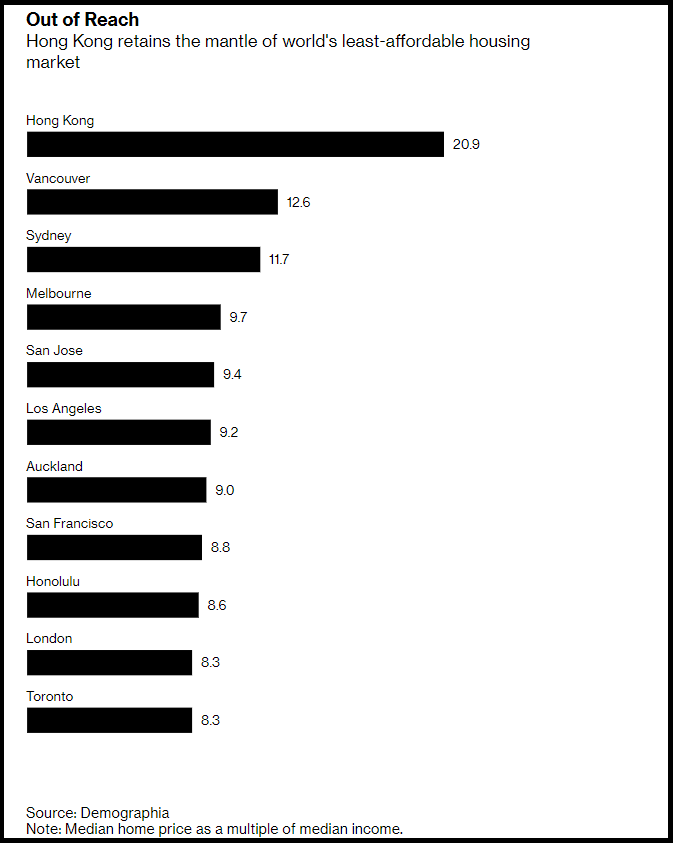

Hong Kong’s real estate has for years been ranked the world’s least affordable. For example, a one-bedroom unit in Tuen Mun in the New Territories — about an hour away from Central, the main business district, by subway — costs the same as a two-bedroom apartment on New York’s upmarket Upper East Side. Prices have risen by 48% over the past five years. According to Demographia, it takes almost 21 years of an average household’s entire income to purchase a home, compared with 12.6 years in Vancouver and 8.3 years in London. Renting is hardly more palatable. Rates for apartments in the ex-British colony are higher than for similar-sized dwellings in San Francisco, New York City and Zurich.

2. Why’s it so expensive?

At first glance, it’s a simple supply-demand mismatch. Hong Kong crams 7.5 million people into 427 square miles (1,105 square kilometers) — roughly the same size as Los Angeles with its 3.9 million people. What’s more, less than 25% of the territory is developed, with 40% of it country parks or nature reserves. That makes Hong Kong one of the world’s most densely populated regions with 17,311 people per square mile. But there’s more to it than that. The city has long been a popular destination for Chinese property investors, while the constant influx of mainland immigrants has underpinned housing demand. There’s also a view among local owner-occupiers, borne out by the relentless climb of home prices, that real estate is a one-way bet.

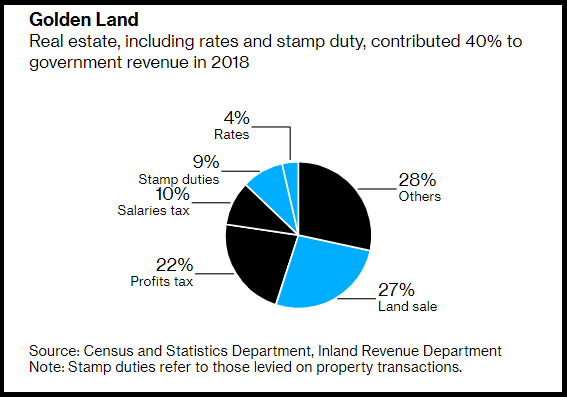

3. How reliant is the government on real estate?

Heavily. Being a low-tax economy, land sales comprised 27% of government revenue in 2018, the biggest single source of funding. The proceeds pay for infrastructure, from building bridges and highways to rolling out IT systems. The city’s property tycoons also hold great sway in local politics. Prominent developers including Li Ka-shing and Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd.’s Adam Kwok are among the exclusive 1,200-member election committee that voted for the city’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, in the last election. Then, some 90% of voters from the real estate sector publicly sided with Lam, the Beijing-approved candidate who has been at the center of protesters’ ire.

4. How does this fuel the protests?

While the ultra-wealthy have built their fortunes on property and live in multimillion-dollar, multi-room houses, at the other end of the spectrum are the masses squeezed into apartments barely the size of parking spots. Some people resort to dwelling illegally in industrial buildings or converted shipping containers. Young people despair they’ll never be able to own their own home, hampering their chances of marriage and having a family. Some demonstrators, filled with the sense they have little to lose, are willing to resort to ever more extreme ways to protest at the expense of the economy. A property market crash? Yes, please. Even Lam herself has said the lack of housing for the young is an underlying issue that needs addressing to resolve the crisis.

5. What’s the government doing?

To be fair, Lam’s administration has been more proactive than previous governments in increasing the supply of land for housing. It’s proposed an $80 billion plan to build four artificial islands equal to about a fifth the size of Manhattan that could house more than 1 million people but would take years to complete. Other ideas such as building on golf courses, barren farmland or open-air parking lots have been floated. Lam has also introduced more government-subsidized apartments, though the supply has come nowhere near to matching demand. But none of the measures has made getting on the property ladder any easier for the majority of people.

6. So there’s no short-term fix?

Not really. And with the government’s authority being eroded by the months-long protests, it’s less likely to put forward any controversial policies, such as the artificial islands. Nearly 6,000 people protested after Lam detailed the project in 2018. Adding to the general unhappiness is the theory outlined by some lawmakers that the government avoids taking land from developers and the indigenous communities in the New Territories because it would be too politically damaging. Those groups are traditionally pro-government.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 09/09/2019 – 18:05![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com