“Bracing For The Worst Crash Of Their Careers”: A Quarter Of All Outstanding CMBS Debt Is On Verge Of Default

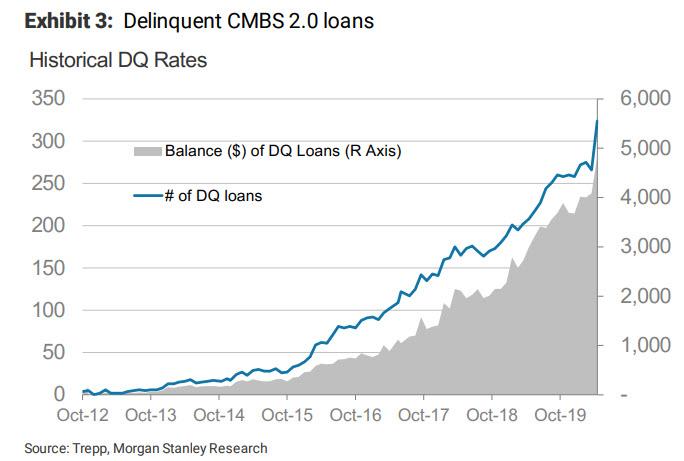

Last week we reported that according to the latest TREPP remittance data compiled by Morgan Stanley, a record 66 CMBS loans totaling $1.0bn became newly delinquent in April, which was the greatest month-over-month change. In total, 324 loans with a total balance of $4.8bn are currently delinquent, which is also an all time high.

What was more troubling than the plain vanilla surge in delinquencies, is the coming deluge of defaults. Recall that a CMBS loan becomes delinquent after it misses two consecutive payments. Loans that have missed just one month of interest are classified as “late but within grace period” or “late beyond grace period”. It is this measure that spiked a record 600bp MoM to ~8.5%.

It now appears that this data was not only somewhat stale but also dramatically underestimated the full severity of the commercial real state catastrophe over the last weeks of April, because according to Fitch data, borrowers with mortgages representing almost $150 billion in CMBS, accounting for 26% of the outstanding debt, have asked about suspending payments in recent weeks – an unprecedented surge in requests for payment relief on CMBS, and an early sign of the severity of the pandemic-induced real estate crisis. Putting this number in context, after the last financial crisis, delinquencies and foreclosures on the debt peaked at 9% in July 2011. So here we are, barely a month into the corona crisis, and the number is already three times greater!

While not all of the borrowers who have requested forbearance will be delinquent or enter foreclosure, Fitch estimates that the $584 billion industry could near the 2011 peak as soon as the third quarter of this year.

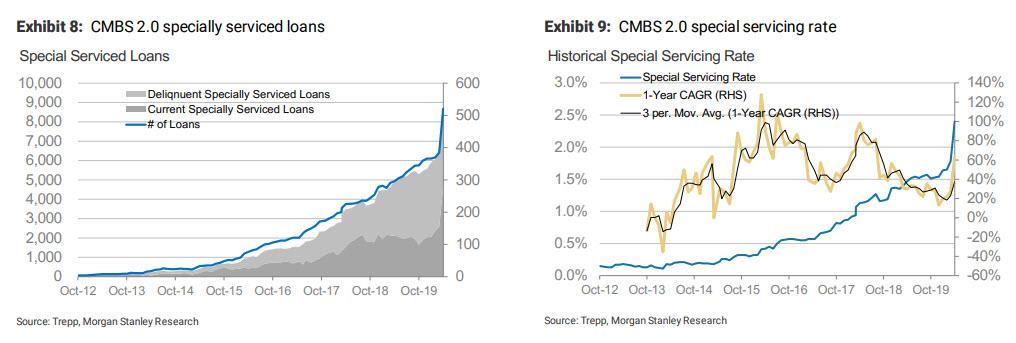

With a deluge of default on deck, the special servicers who handle vulnerable CMBS loans, are bracing for what Bloomberg called “the worst crash of their careers”, by which of course it meant best, because the more the default, the greater the payday for the special servicers. They’re staffing up following years of downsizing to handle a wave of defaults, modification requests and other workouts, including potential foreclosures.

“Everything is happening at once,” said James Shevlin, president of CWCapital, a unit of private equity firm Fortress Investment Group and one of the largest special servicers. “It’s kind of exciting times. I mean, this is what you live for.”

AS discussed last week, unlike the last financial crisis which was ignited by a surge in residential foreclosures as the housing market was one giant bubble, now commercial real estate is getting hit not because of outsized valuation but because of collapsing cash flows with the economic shutdown shuttering stores and putting travel on ice.

Making matters worse is that unlike residential real estate, there’s no bailout relief plan for commercial real estate, and while bankers usually have leeway to negotiate payment plans on commercial property, options for borrowers and lenders are limited for CMBS and foreclosure is usually a quick end to any delinquency or default.

Meanwhile, as we reported last week, the debt transferred to special servicers from master servicers, mostly banks that handle payment collections, is already swelling. Unpaid principal in workouts jumped to $22 billion in April, up 56% from a month earlier, according to the data firm Trepp.

Similar to the mob, special servicers make money by collecting outstanding debt and charging fees based on the unpaid principal on the loans they manage. Most are units of larger finance companies. Midland Financial, named as special servicer on approximately $200 billion of CMBS debt, is a unit of PNC. Rialto Capital, owned by private equity firm Stone Point Capital, was a named special servicer on about $100 billion of CMBS loans. LNR Partners, which finished 2019 with the largest active special-servicer portfolio, is owned by Starwood Property Trust, a real estate firm founded by Barry Sternlicht.

Quoted by Bloomberg, Sternlicht said during a conference call on Monday that special servicers don’t “get paid a ton money” for granting forbearance.

“Where the servicer begins to make a lot of money is when the loans default,” he said. “They have to work them out and they ultimately have to resolve the loan and sell it or take back the asset.”

In other words, special servicers are about to make a killing.

And again, just like the mob which thrives in times when other sources of funding are scarce, special servicers often play hardball, demanding personal guarantees, coverage of legal costs and complete repayment of deferred installments, according to Ann Hambly, chief executive officer of 1st Service Solutions, which works for about 250 borrowers who’ve sought debt relief in the current crisis.

“They’re at the mercy of this handful of special servicers that are run by hedge funds and, arguably, have an ulterior motive,” said Hambly, who started working for loan servicers in 1985 before switching sides to represent borrowers.

On the other hand, perhaps comparisons to the mafia are a bit exaggerated: fears about self-dealing are overblown according to Fitch’s Adam Fox, whose research after the 2008 crisis concluded most special servicers abide by their obligations to protect the interests of bondholders: “There were some concerns that servicers were pillaging the trust and picking up assets on the cheap,” he said. “We just didn’t find it.”

Maybe Fitch just didn’t look hard enough. After all, it wouldn’t be the first time that a rating agency has missed something rather big starting it right in the face.

Mob or not, it’s time for special servicers to party because after nearly a decade of downsizing where anyone could obtain or refi a loan on even cheaper terms, it’s jackpot time. Also unlike the last crisis, this time the spoils will be shared by far fewer: the seven largest firms employed 385 people at the end of 2019, less than half their headcount at the peak of the last crisis.

The good news is that once a debt collected, always a debt collected, and Miami-based LNR, where headcount ended last year down 40% from its 2013 level, is calling back veterans from other duties at Starwood and looking at resumes. CWCapital, which reduced staff by almost 75% from its 2011 peak, is drafting Fortress workers from other duties and recruiting new talent, while relying on technology upgrades to help manage the incoming wave more efficiently.

“It’s going to be a very different crisis,” said Shevlin, who has been in the industry for more than 20 years. And while commercial real estate borrowers are bracing for the “worst crash of their careers”, the special servicers – and other debt collectors – are about to enjoy the biggest bonanza they have ever seen.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 05/05/2020 – 21:45![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com