NYC’s Army Of 3,000 COVID-19 ‘Contact Tracers’ Have Accomplished Surprisingly Little

Tyler Durden

Sun, 06/21/2020 – 21:15

As officials and experts around the world continue to stubbornly insist that contact tracing is ‘the answer’ to preventing a resurgence in new cases once economies reopen, even as a growing body of research suggests that the virus spreads most quickly among members of the same household, and less frequently via asymptomatic ‘carriers’ (though it surely does happen), New York City is finding that the ‘army’ of contact tracers raised by Mayor Bill de Blasio is much less useful than officials had hoped, according to a report in the New York Times published one day before the city enters its second phase of reopening.

with outdoor dining, in-store shopping and office work resuming tomorrow, the first batch of data from the program, which began on June 1, indicates that the tracers are usually unable to locate infected people or gather any useful information from newly infected subjects. Interestingly, the biggest ‘obstacle’ to obtaining this information is the patients themselves: Only 35% of the 5,347 city residents who tested positive or were presumed positive for COVID-19 in the program’s first two weeks gave information about close contacts to tracers, the city said.

If anything, this failure suggests that contact tracing in this manner simply isn’t an effective tool for preventing a second wave of the virus, though states have many other tools, including widespread testing and quarantining the sick and vulnerable. Instead, the NYT suggests the failure is a “worrisome” sign that “the difficulties in preventing a surge of new cases as states across the country reopen.”

Though contact tracing has worked in the past during outbreaks of tuberculosis and measles, the technique appears to be much less useful when implemented on the scale of the coronavirus, officials are finding. However, other countries have reported more success with these techniques, including China, South Korea and Germany and other countries have set up extensive tracking networks that have helped identify potentially infected individuals before they become seriously symptomatic.

In South Korea, for example, people at weddings, funerals, karaoke bars, nightclubs and internet-game parlors write down their names and telephone numbers, and the authorities have been able to draw on cellphone location data. Of course, all of this relies on the subjects being willing to give out their information.

But when American tech behemoths instead decide to surreptitiously install tracking apps without the direct consent of the user, well, let’s just say it doesn’t exactly help establish the trust and confidence that’s critical for these programs to work.

One of the program’s leaders told the NYT that while things are getting off to a less-than-ideal start, there are signs that NYC’s program could help prevent another outbreak. For example, at least most of the patients who are being contacted are at least answering the phones.

Dr. Ted Long, head of New York City’s new Test and Trace Corps, insisted that the program was going well, but acknowledged that many people who tested positive had failed to provide information over the phone to the contact tracers, or left interviews before being asked. Others told the tracers they had been only at home and had not put others at risk, and then did not name family members.

Dr. Long said one encouraging sign was that nearly all the people for whom the city had numbers at least answered the phone. He added that he believed that the tracers would be more successful when they start going to people’s homes in the next week or two, rather than just relying on communication over the phone.

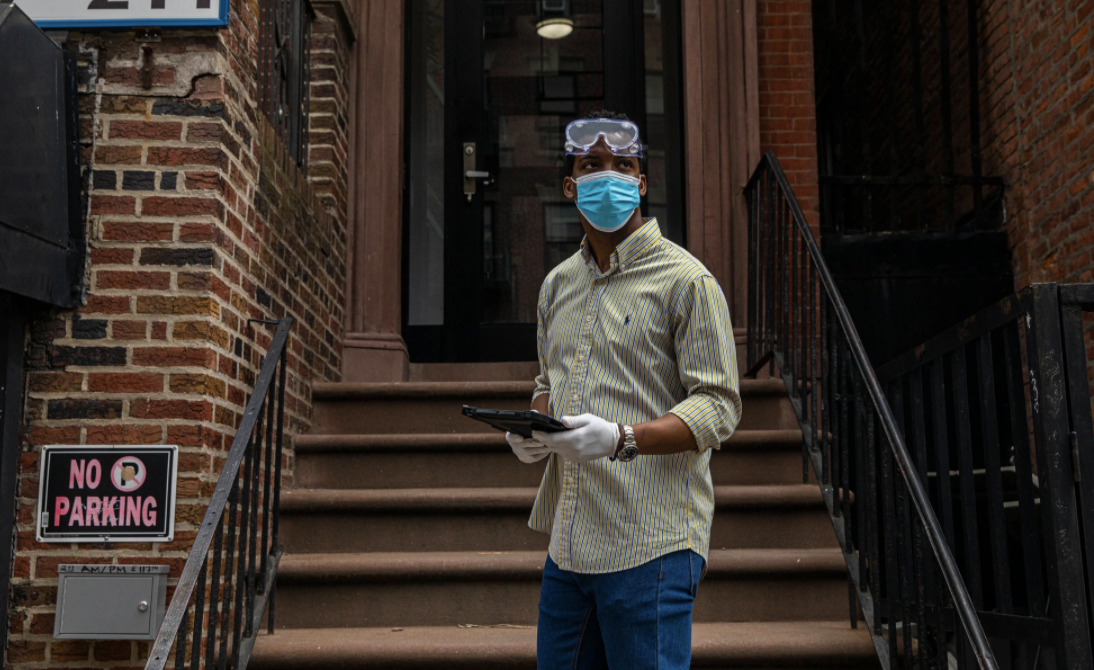

The NYT then spent most of the piece focusing on individual contact tracers from minority backgrounds who had been assigned to canvass patients in more ‘economically disadvantaged’ neighborhoods.

But another expert quoted by the NYT pointed out that Mayor de Blasio’s decision to establish the corp of contact tracers outside the City Department of Public Health would ensure that all the contact tracers lack the experience for this type of work.

Dr. Halkitis at Rutgers said he thought the low cooperation rate was likely due to several factors, including the inexperience of the tracers; widespread reluctance among Americans to share personal information with the government; and Mayor de Blasio’s decision to shift the program away from the city’s Department of Health.

“You have taken it away from the people who actually know how to do it,” he said. “The D.O.H. people, they are skilled. They know this stuff.”

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com