Biden Will Hike The Top Capital Gains Tax Rate To 39.6%: What That Means For Markets

Tyler Durden

Sat, 10/10/2020 – 15:30

Over the past few weeks, Wall Street has been busy carefully restructuring the post-election narrative to one where the tax hikes under a Biden presidency would actually be bullish for risk assets.

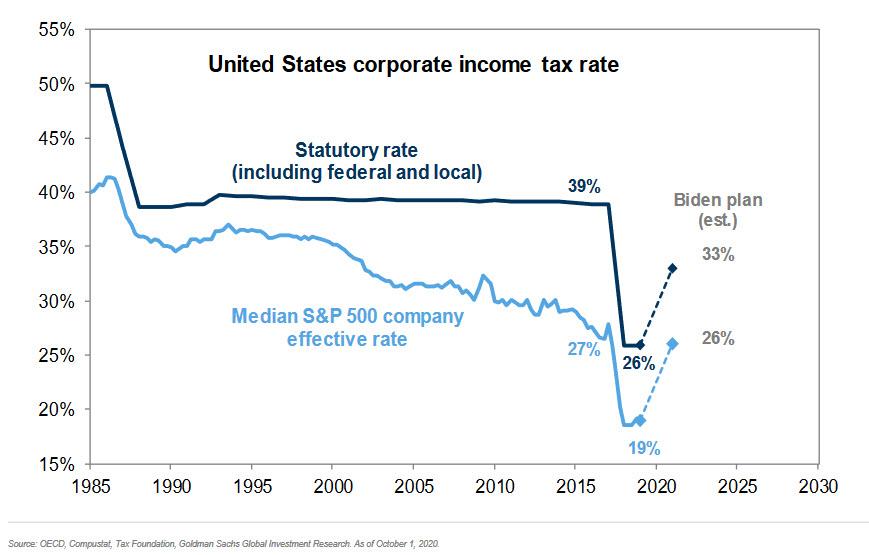

As a reminder, whereas there would be no changes to the tax regime under a 2nd Trump administration, Biden plans to lift the statutory corporate income tax rate by 7% to 33% from 26% (including federal and local) reversing half of the Trump cuts, raising taxes on high earners as well as implementing a number of other tax changes including an increased tax on global, low-tax, intangible (“GILTI”) income…

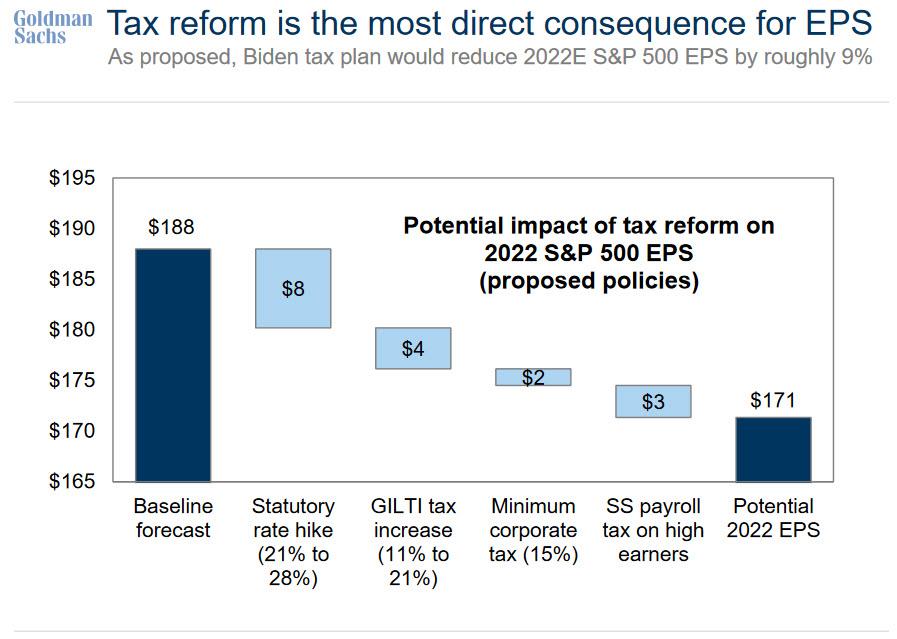

… which the banks readily admit would adversely hit S&P500 earnings in 2022 by roughly 9%, pushing it from a Goldman baseline forecast of $188 to $171…

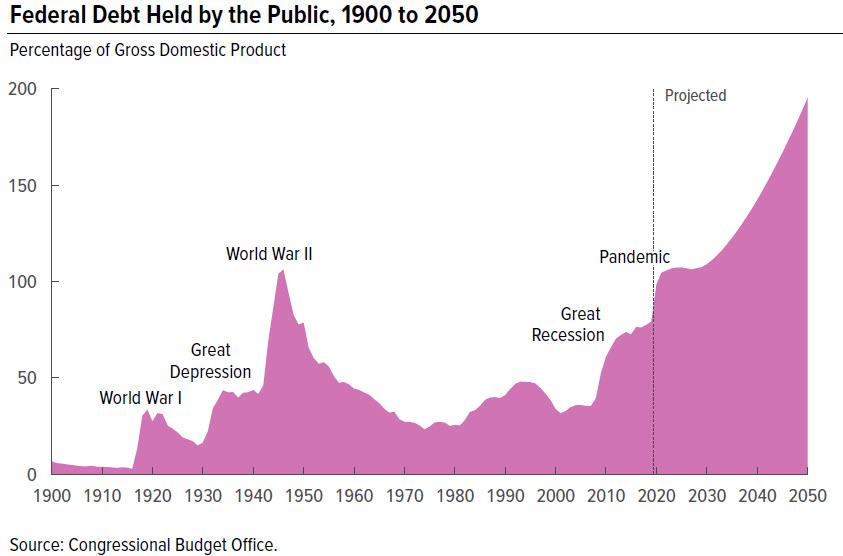

… yet ignore all that because, as per the new Wall Street narrative, the Biden admin would also unleash up to $7 trillion in fiscal stimulus which while catastrophic for the long-term viability of the US, its currency and its already ridiculous debt trajectory…

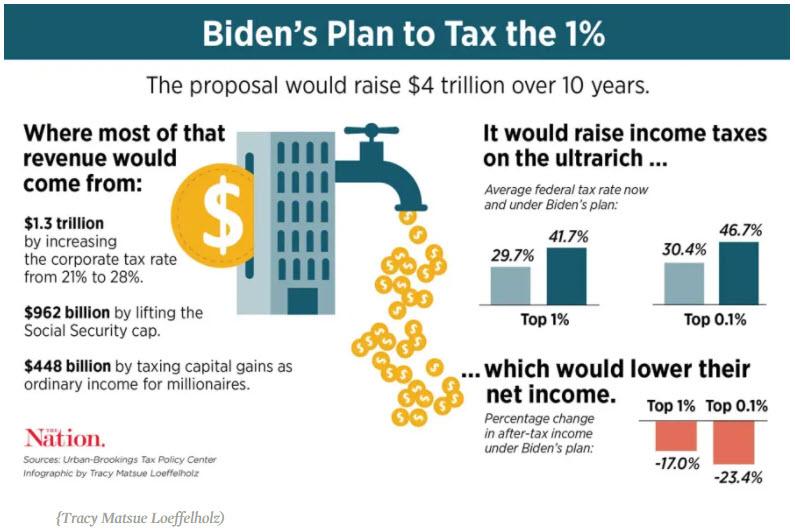

… would be good for stocks until some time in 2023, at which point even more stimulus will be needed (according to the latest Goldman research). As a result, and as we summarized last week, Wall Street now agrees that Biden victory and a Democratic sweep would be great for stocks despite the sharp increase in taxes across the board for many Americans and especially the Top 1…

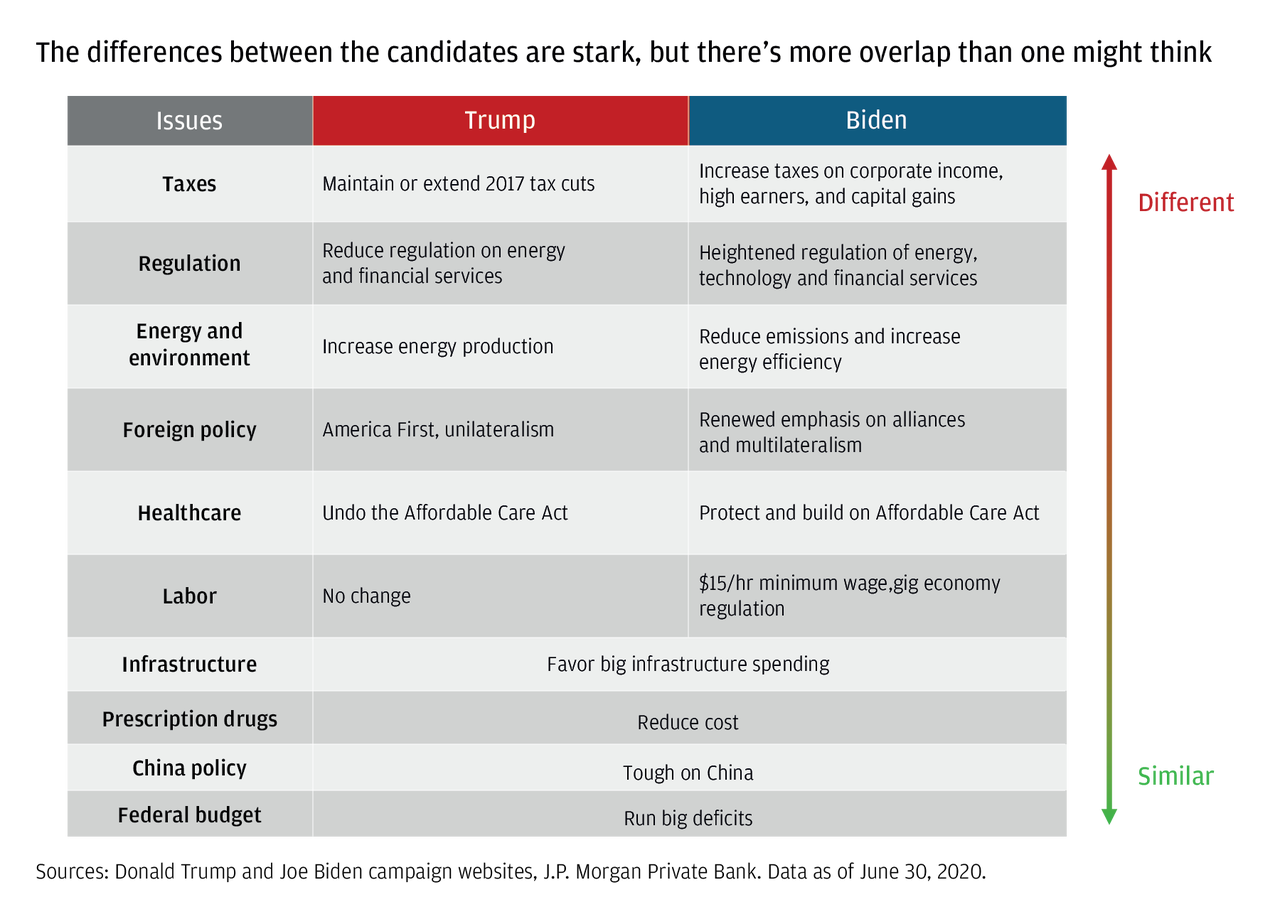

… which as JPMorgan has shown previously, is the one issue where the two candidates differ the most.

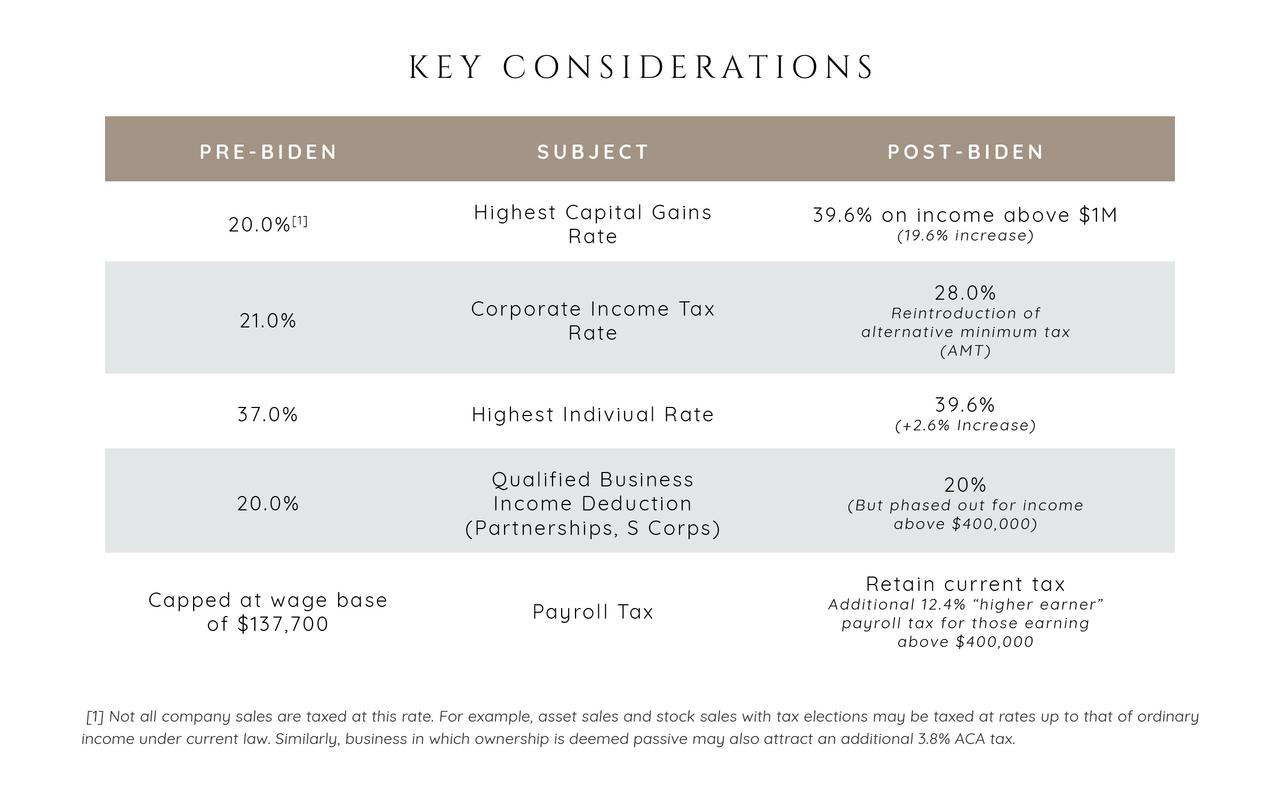

It remains to be seen just how ‘good’ for stocks a sharp hit to EPS and a potential contraction in PE multiples – which would be sparked by Biden’s aggressively reflationary policies – will be under a Biden presidency, but one aspect of Biden’s tax policies that has received very little coverage is his proposal to increase the maximum tax rate for long-term capital gains by a whopping 66%, from 20% currently (23.8% when accounting for the additional 3.8% ACA tax) to as high as 39.6%, for those making over $1 million, or for proceeds of a business sale over $1 million. A summary of the changes tot he US tax code under a Biden admin is shown below.

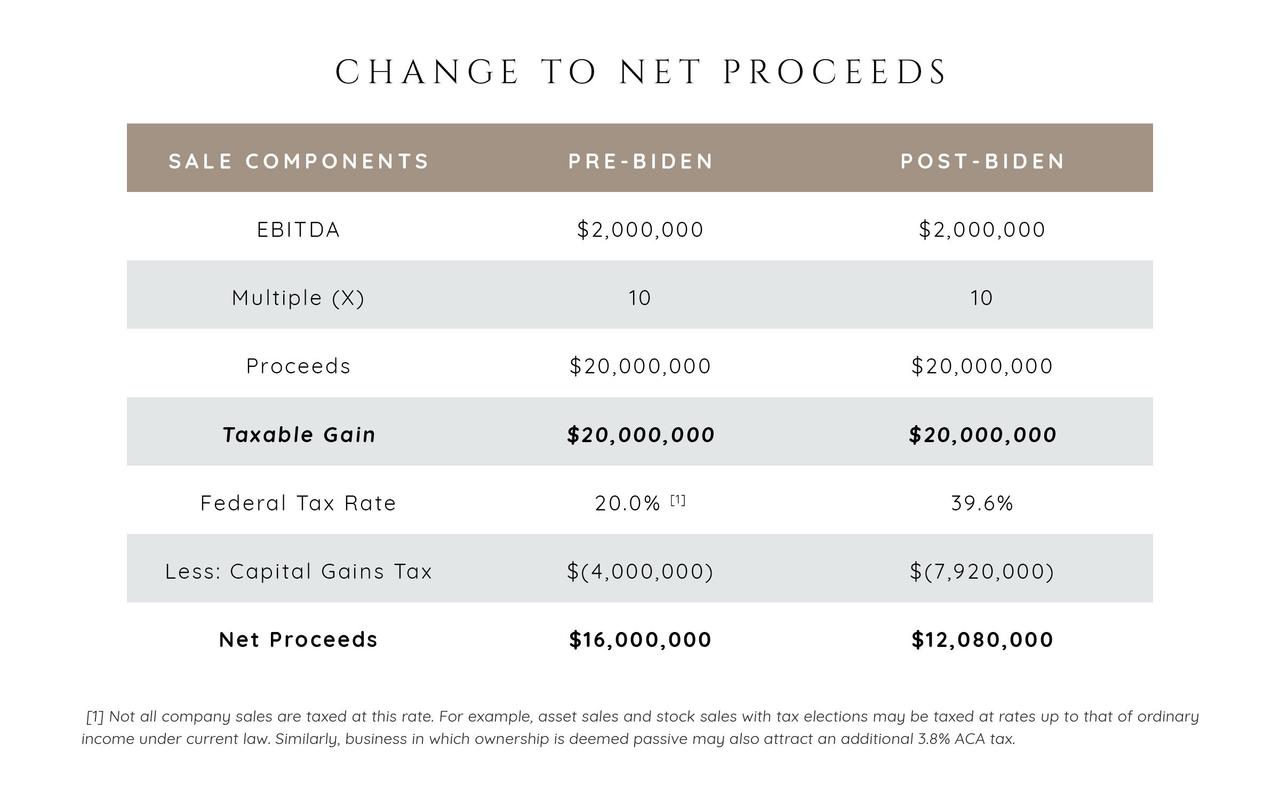

While this cap gains increase won’t affect most Robinhood traders (except for the really talented ones), it will have a drastic hit on major market players and corporate strategies involving exit events that include more than $1 million in proceeds, as the following analysis from Benchmark Corporate shows: assume a $2.0M EBITDA (small or medium) business receives a valuation multiple of 10x for a total transaction value (taxable gain) of $20.0M. Under the Biden Plan, the seller would lose $3.92M in the sale. To receive the same net proceeds, a multiple of 13.2x would need to be secured.

This kind of dramatic revision to post-transaction cash flows under a Biden regime is – to say the least – concerning, although because the media has barely discussed Biden’s tax plan (or any of his other policies for that matter) and instead focusing on Trump, Trump, Trump, the impact of Biden’s tax long-term cap gains will come as a shock to the market.

It’s also why on Friday, JPMorgan was quick to jump on the bandwagon of Wall Street defenders of Biden tax proposals – after all no bank wants to see the markets puke in the coming weeks as traders lock in profits under the Trump admin – only instead of defending the corporate tax hike, this time it focused on Biden’s cap gains tax hike. Not surprisingly, it concludes that this too would have “little impact on risk taking and investors’ attitude toward equities as an asset class.”

But first, some background.

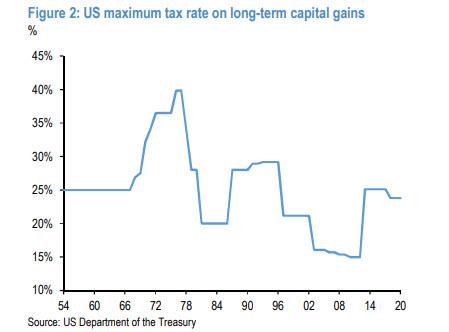

As JPM’s quant Nick Panigirtzoglou writes, while it is relatively easier to quantify the potential impact from Biden’s corporate tax or other proposals, assessing the potential impact from the proposed increase in the capital gains tax rate is more difficult. Biden’s proposal is for the maximum tax rate for long-term capital gains to rise to 39.6% from 23.8% currently, a 66% proportional rise. As the JPM strategist concedes, “given the size of the proposed increase, the potential impact is likely to be at least similar to previous episodes of big capital gains tax rate hikes, i.e., the capital gains tax rate hikes of 1 January 1987 and 2013.”

Between the 1986 and 1987 tax years, the maximum tax rate on long-term capital gains had risen to 28% from 20%, a 40% proportional rise. Between the 2012 and 2013 tax years, the maximum tax rate on long-term capital gains had risen to 25.1% from 15%, a 67% proportional rise.

At this point, Panigirtzoglou launches an assessment of the potential impact from Biden’s proposed capital gains tax increase, in which he distinguishes between the longer-term and the near-term impact.

In terms of the longer-term impact, the quant falls back on conventional wisdom which says that “the friction from a higher capital gains tax would over time reduce capital mobility and investment and thus end up being negative for economic growth and thus for long-term equity market returns. The argument being that higher taxes on capital gains would lower the after-tax rate of return to savers, which in turn would raise the cost of capital to businesses. In addition, a higher capital gains tax rate could reduce incentives for entrepreneurship and risk taking.”

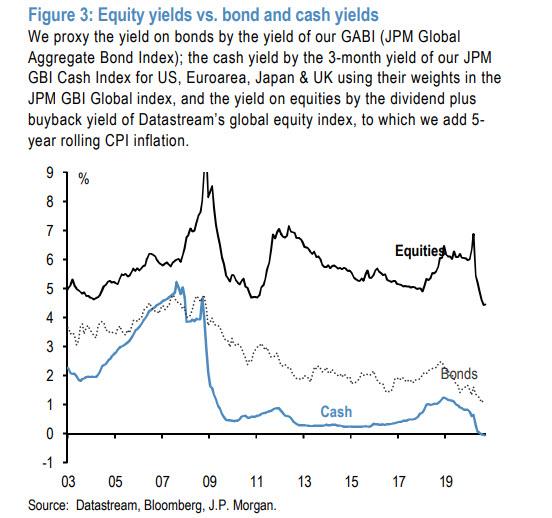

Needless to say, all of this is bad for the broader economy, which is why Panigirtzoglou is quick to admit that a full-blown analysis of the economic impact of a capital gains tax hike “is beyond the scope of this publication” which is ironic because the very next thing he does is an attempt to spin it as favorable because, as he writes, “in a low yield and high equity risk premium environment like the one we are at the moment (Figure 3), any longer term impact from a capital gains tax rate hike on risk taking and investors’ attitude towards equities as an asset class would be even more muted relative to the past.”

In other words, under the massive yield and volatility suppression of the current Fed regime, despite the adverse impact of higher taxes, investors will still have no choice but to go back to stocks.

One wonders how this argument will be “spun” if after a few years of Biden’s trillions in fiscal stimulus, the current “low yield and high equity risk premium” environment is dramatically reversed. Of course, we are confident that JPM will have a bullish spin for that when the time comes.

And just in case that was not enough, Panigirtzoglou then suggests another “positive” aspect of higher cap gains taxes: “an argument could be made that the money invested by individuals in the equity market would likely become more sticky over time as a result of the increase in the capital gains tax rate, perhaps inducing lower long-term equity volatility.” Yes, because the Fed’s constant manipulation of markets by lowering implied and realized vol is not enough.

And while it is easy to spin any long-term scenario as bullish laden with countless favorable assumptions, even JPMorgan finds it impossible to spin the near term impact as bullish: “There is little doubt, that similar to the past, tax optimization would result in one-off bout of asset selling ahead of the effective date of the capital gains tax rate hike so that investors realize their capital gains before the new higher rate applies. “

History is full of such examples: before at the end of 1986 and 2012 ahead of the 1 January 1987 and 2013 increase in the capital gain tax rate.

So assuming Biden becomes President and controls the Congress to be able to implement his plan to increase the capital gains tax rate next year, the most likely effective date JPM envisages is 1 January 2022. In this case, any tax related asset selling would take place in the fourth quarter of 2021, i.e., a year from now. Which brings us the key question: how much tax-related asset selling should we expect at the end of 2021 assuming an effective date of the new capital gains tax rate of 1st January 2022?

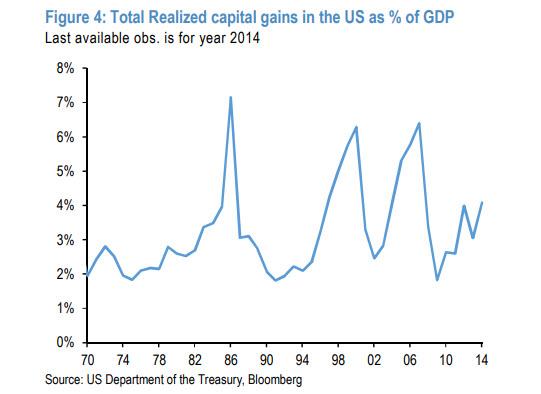

One way of answering this question is to look at the experiences of 1986 and 2012. Figure 4 shows the capital gains realizations in the US as % of US GDP. One can clearly see the big annual increase in US capital gains realizations during 1986 and 2012, by 3% and 1.5% respectively of US GDP. Applying an increase of 2% of US GDP in capital gains realizations in the current conjuncture would imply additional tax-related asset selling of around $400bn due to the prospective increase in the capital gains tax rate.

According to JPM, “such selling would likely put some pressure on the US equity market of around 5% or so as we saw previously at the end of 1986 and 2012 (Figure 5).” However at this point the short-term becomes long-term (similar to how traders become investors after bad trades), and as Panigirtzoglou next posits, “such pressure is likely to be temporary and once the new capital gains tax rate is introduced, the equity market would likely resume its uptrend in even stronger manner.”

Indeed, Figure 5 shows that following a negative to flattish profile in the fourth quarter of 1986 and 2012, the equity market saw a steeper upward trajectory in the first half of 1987 and 2013, i.e. the equity market corrections at the end of 1986 and 2012 proved good buying opportunities. In particular, in 1986 the S&P had seen annualized price returns of around 15% per year on average in the 5 years before the tax rise. In 2012, a 5-year horizon covers the financial crisis, but using a shorter horizon between 2 and 4 years saw annualized gains of 6-12%. And in the first quarter of the year the new higher rate had kicked in, the S&P saw returns of 20% and 10% respectively.

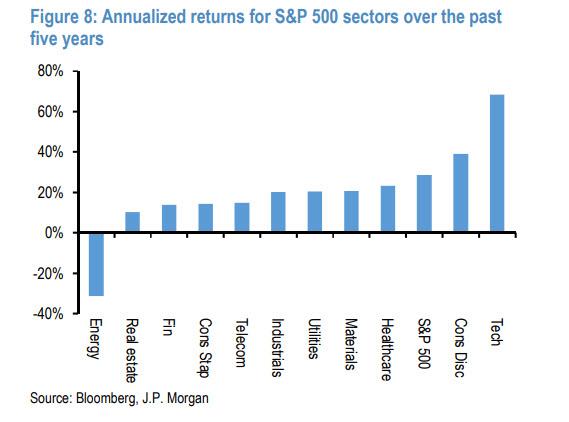

Going back to the less than bullish short-term, JPM next looks at which sectors would be most impacted from the Biden tax changes, and finds that in the event of a Democratic sweep that subsequently sees a change in CGT rates taking effect at end-2021, “the sectors that have outperformed in recent years recent years are susceptible to some volatility around the time when a new higher CGT rate would kick in. Looking at the annualized returns over the past 5 years (Figure 8), this implies sectors

such as tech, consumer discretionary and healthcare.” By contrast, investors might prefer to wait until after the new higher CGT rate kicks in before harvesting tax losses from sectors and companies that have seen weaker returns (e.g. energy) at a higher CGT rate.”

Putting it all together, JPM concludes that even if there is a Blue Sweep in November, “it is perhaps too early to worry about a prospective capital gains tax rate increase in the US” as the likely effective date of the higher capital gains tax rate would be January 2022. As such, JPMorgan admits that “we are likely to see some downward pressure in equity markets in Q4 2021, i.e., in a year’s time.”

Of course, since such a conclusion in isolation would be viewed as too bearish for a bank whose job is to pump markets, JPM then engages the spin cycle, and writes that “once the new capital gains tax rate kicks in, the equity market is likely to resume its upward trajectory in a strong manner as it did previously in the first quarter half of 1987 and 2013.” Because why not: after all the Fed is there to make sure stocks never again suffer the indignity of another bear market.

Finally, and somewhat laughably, JPM writes that “longer term we see little impact from a prospective capital gains tax rate increase on risk taking and investors’ attitude towards equities as an asset class given the current low yield and high equity risk premium environment.”

To summarize: in its quest to spin a Biden administration as positive for risk assets, perhaps even more so than Trump’s, first we had a barrage of banks predicting that the jump in corporate tax rates under president Biden would be a non-event for markets (since it will be offset by trillions more in stimulus), and now we have the largest commercial US bank vouching that an even more draconian increase in capital gains tax may be negative around the end of 2021, but will then supercharge returns in the years after.

So yes, it’s possible that we now live in such an upside down world where Biden’s higher tax rates are bullish for markets… just as Trump’s tax cuts were bullish for markets (here, the question emerges, is there any event than in Wall Street’s view is ever negative for markets, or rather centrally-planned “markets” in which the Fed injects at least $120 billion every month), although we doubt it; after all these forecasts come from the same Wall Street which was dead certain that Trump defeating Clinton would lead to a market crash (we all know what happened then). In any case, now that JPM has done the initial spin cycle on why higher capital gains taxes are bullish for stocks, we expect all other banks to join in the coming days with their own narratives on why the only thing more bullish for stocks than lower taxes is higher taxes.

Finally, since this is all just spin, we leave the final word to another branch of JPMorgan, its Private Bank (which handles all of the bank’s high net worth clients), whose conclusion is that no matter what happens, one should not sell:

Since the end of World War II, there’s been this one constant, regardless of the occupant of the White House and the composition of Congress: equity markets have increased in value over time. Some stocks, sectors or styles do better at some times than others, depending on specific, often unpredictable factors—a fact that underlines the importance of diversification. That is why, to ensure the long-term health of one’s portfolio, we think that time in the market, rather than market timing, is key. Consequently, we advise clients to stay invested, regardless of specific events—including election results.

The punchline: despite the clear differences to the tax regime under a Biden administration, JPMorgan goes so far as to say ignore it all, and in fact, “don’t let the passions of this election lead you to make any key planning or investment decisions.”

In light of all this, one wonders: does it even matter who is president as long as we have a Fed?

![]()

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com