Term Premiums Least Rewarding Since Volcker’s Day

By Ven Ram, Bloomberg Markets Live strategist and commentator

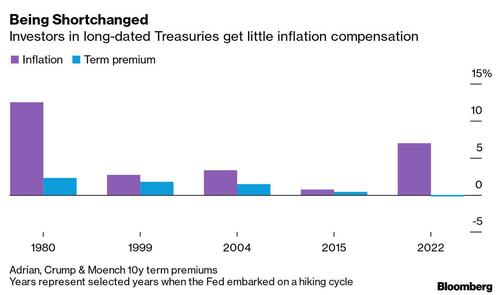

Not since Paul Volcker’s time at the Federal Reserve have investors sought so little from long-dated Treasuries in relation to inflation as they do now, underscoring the aggressive scope for policy tightening that may lie ahead.

Term premiums juxtaposed alongside realized inflation have not been this low since 1980. Back then, inflation was running in double digits. Volcker, who took the helm in August 1979, began raising rates dramatically to get inflation under control.

Term premium is the compensation investors seek to lock their money in longer-dated bonds rather than shorter maturities in return for the liquidity, credit and inflation risk they take on. With Treasuries specifically, the gauge measures the risk that price increases may not evolve in line with expectations.

With inflation running at 7%, the Fed has significantly ramped up its rhetoric against prices since Fed Chair Jerome Powell was nominated for a second term in November. Earlier this week, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard — an influential voice within the policy committee — said that current market pricing for five interest-rate increases this year is not a bad bet.

#Bonds are still shakin’ from #Fed Look at collapse in daily Treasury term premia… warning, warning… pic.twitter.com/R7KcBHi9j2

— CrossBorder Capital (@crossbordercap) February 2, 2022

Even with such aggressive rate hikes being built into market expectations, term premiums haven’t budged meaningfully so far this year, underscoring how the Fed’s humongous balance sheet may be preventing long-dated yields from climbing.

The Fed embarked on $120 billion a month of bond purchases after the pandemic first struck, taking its holdings to an unprecedented $8.86 trillion at last count. Its buying has gone at a frantic pace of $1 million a minute since the start of the financial crisis.

My calculations suggest that the 10-year nominal yield may fail to breach 2.25%, levels last seen before the pandemic, even if the Fed’s policy tightening successfully raises the 10-year real rate to -0.15%, about 50 basis points higher than where we are now.

While the Fed is now on course to conclude its bond purchases and perhaps start trimming its balance sheet, the effect of its holdings may still be felt for long.

Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe observed last year that “central bank bond purchases have their impact through the total stock of bonds purchased, not the flow of those purchases.” That may also apply to the U.S.

The pace of any Fed balance-sheet runoff does matter to the markets. While Powell remarked recently that he is “willing to move sooner than we did the last time and also perhaps faster,” he added that the Fed wants the balance sheet to decline “in a predictable manner… declining primarily by adjusting reinvestments.”

In other words, the bulk of those assets on the Fed’s balance sheet won’t come into the open market anytime soon, suppressing yields more than would otherwise be the case.

Whatever the Fed’s intentions on rates, it’s clear that long-dated yields and those depressed term premiums will require more than just raising its benchmark. The question is if the Fed will be as brave in paring down its balance sheet as it was in building it.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 02/04/2022 – 06:30

Zero Hedge’s mission is to widen the scope of financial, economic and political information available to the professional investing public, to skeptically examine and, where necessary, attack the flaccid institution that financial journalism has become, to liberate oppressed knowledge, to provide analysis uninhibited by political constraint and to facilitate information’s unending quest for freedom. Visit https://www.zerohedge.com